A few weeks ago, we talked with Montana artist Aaron Schuerr about his preparations for a solo painting and backpacking trip from rim to rim of the Grand Canyon. We checked back in with him afterward to see if he would do anything differently. His final report is an interesting one….

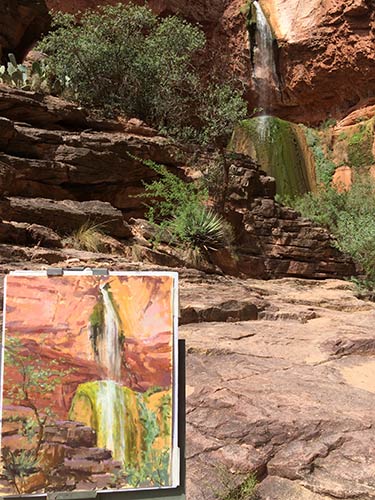

Lead Image: Aaron Schuerr painting on location in the Grand Canyon during his recent solo backpacking trip

Schuerr reports that his preparations were pretty much spot-on, but there was one area in which his preparations proved crucial, and it was not something that one could buy online or quickly manufacture: Schuerr was in excellent physical shape before starting this 23-mile trek. “I am conditioned for a trip like this — both to carry a heavy pack and cover the miles, but also to stand in the sun and paint, and in doing so to listen to my body and know when it is time to find shade, go for a swim, and get some calories in me. I don’t say any of this to brag, but just to make it clear that a trip like this is not something to take lightly. Rescues generally happen because people are unrealistic about what they are capable of — they just don’t have the experience to know when they are in over their heads. Just be sensible about what you are capable of. I would equate the mental and physical difficulty of adding painting to backpacking trip to a technical mountaineering trip.”

Heat was one of his main concerns before the trip, and it proved to be one of the hardest obstacles to navigate, even in the canyon’s monsoon season, when rain and cooler temperatures arrive. “One of the benefits to monsoon weather is that the temperatures were fairly mild,” reports Schuerr. “While temps at the bottom frequently peak at over 100 degrees, it barely crested 90 the whole trip. (Of course, 90 degrees with desert sunshine is still hot!) Fortunately, the whole route follows creek drainages — there wasn’t a day that I didn’t find a good swimming hole to jump in. (There are some fantastic swimming holes — three had waterfalls flowing right into them.) I was also thankful that I had been so obsessive about electrolytes. I had Gatorade to mix into the water, GU packets (a paste that has sodium, protein, electrolytes, etc., designed for endurance athletes), and a big bag of peanuts. This helped me endure all that time in the sun.”

Schuerr continues, “I feel it’s important for me to sound a caution to others that might think of doing a trip like this: Painting and trekking is crazy hard work. Most hikers were up and packing well before sunrise. Conventional wisdom is to start before sunrise and be off the trail by 10 a.m. if possible. I’d start before sunrise, paint until 11 or 12, and then hike fast and hard to cover the miles. I usually made it to the next camp by early afternoon, raced to set up camp, and then headed out again to paint till dark. Basically, I did everything you are not supposed to do! I painted when most were hiking, and I hiked while most were hiding out in the shade or lounging in the creek.”

The rigors of the trek presented Schuerr with another issue. “One of the benefits of working roadside is that you can check out a spot, get in the car, check out another, even a third, and then choose between them,” he says. “On a trek it isn’t really practical to compare potential painting sites. It forced me to make a decision one way or another and go for it. In some ways this was good for me — decisiveness is not always my strongest suit. However, there were times that I committed to one location only to find a more interesting one further down the trail. More than once I just had to take pictures and move on — either it had gotten too hot, or I felt the pressure to make it to camp before dark. In some ways it would have been nice to have some familiarity with the country before I tried to paint it.

“I also felt the pressure to cover the miles, to get to camp before it got too late. After all, I was trekking alone through some wild country. I just felt like it was important to get to camp and get unpacked and get my tent pitched. On the average day, I still painted for at least one morning session, usually at sunrise, before covering a lot of miles. Looking back on the trip, I really needn’t have worried — the trail was wide and obvious, and I was hiking to backcountry campgrounds with outhouses, water taps, and designated sites with picnic tables. I could have wandered in at any time, though I think that trekking solo has taught me to err on the side of caution. I’ve spent enough time in the wild to know that I must never be cavalier about the seriousness of the endeavor.”

In the end, Schuerr was left thinking about what went right and what he got out of the trip. He produced two paintings a day plus some unfinished sketches, which is rather impressive considering how much time and effort he had to devote to hiking and setting up camp. But he can organize the “perks” of a trek like his into four broad groups:

- Although I value the camaraderie of a plein air festival, solitude is at the heart of my work. I crave it. It is at the heart of my creative process. I thought that in six days I would get lonely, but I was so totally “in the moment” that all extraneous thoughts evaporated. I entered into a slow and steady rhythm of the canyon, and it enthralled me. It’s hard to describe how essential solitude is to the creative process. I experienced total immersion. It was as though the canyon lured me in and then unfolded its secrets. I’m suspicious of mysticism, and yet I can only describe an experience like this in mystical terms.

- I realized that I had a conception of the canyon based on what I had seen from above, but the sheer diversity of ecosystems floored me.

- At Phantom Ranch I was given the opportunity to speak in place of the 4 p.m. ranger talk. I did a brief show-and-tell of the work I had produced up to that point, and then a short mini-demo. I told them, “The main difference between you, the hiker, and me, the artist, is that you look around and enjoy the beauty. I ask what makes it beautiful.” I then talked about some basic qualities that an artist looks for in the landscape: pattern, contrast, color, reflected light, and the like. The next morning two women ran up to me and said, “We just spent the whole evening out looking, and after your talk, everything looked different!” Made me smile. The last evening, I painted out at Plateau Point. A backpacking guide had his clients out to enjoy the sunset while he took out his backpacking stove to cook dinner for them. We chatted as I struggled to paint through intense wind gusts. As the sun dipped and I started to pack up, he invited me to join them for dinner. “We have plenty,” he assured me. It was a spectacular sunset, and the meal tasted fantastic. We walked the mile-and-a-half back to camp in the dark and I learned about the long history of native tribes in the canyon. In general, people were really inspired by the trek and the work — it proved to be a fine way to connect with people.

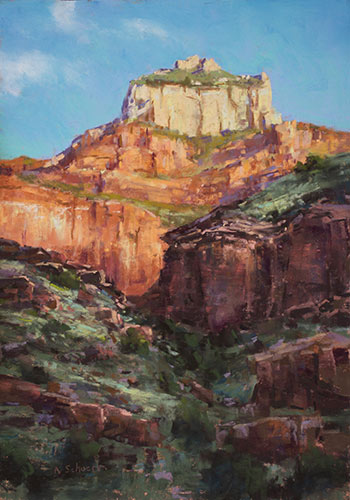

- Painting the canyon was challenging! It took me a couple of years to learn to paint from the rim, and now I had to learn to paint it from beneath the rim. The Grand Canyon from any angle is a worthy challenge, complicated and overwhelming. I enjoyed every moment, but not every painting was great. At the back of my mind I knew that I was going to have to frame up work for the Grand Canyon Celebration of Art. In some ways it was hard to be traveling through so much new country while knowing that I needed to produce work worthy of a frame. In a way it motivated me to work harder and stay focused. Often when I have painted from the rim, I’ll go back a second day or even a third to finish a painting. The light just changes so quickly, and I have a level of finish in mind. On the trek I just didn’t have that luxury. I had to finish work in a single session. This forced me to be very intentional — get a solid sketch done, block in the shadow shapes, get the average colors in, and get to the point quickly. In a way, the very nature of the trip really whipped me into shape — forced me to work simply and with intention — no finessing. It was really good for me. In some ways I feel like I could do even better work with another trip — I’ve made a step toward learning the unique language of the canyon.

I appreciate the unique language of an artist that ventures into “unknown” territory while expending much of themselves to capture the “heart” of the landscape – It is not without blood, sweat and tears. Thanks for sharing your crazy hard work with fellow outdoor painters and offering your insights. This was an enjoyable read.