In this series of articles, Utah artist J. Brad Holt talks about what artists are seeing as they look at the landscape. Holt studied geology in college and is attentive to what the rocks suggest in the scenes he paints.

We marvel at rocks. We build with them, and build around them. We walk around on a world composed of them. Some of us even paint them. But what are they? What is their composition? How were they formed? How did they come to be where they are, and why do they look as they do? These are the basic questions that open the gates of geology, but I must warn you: Once you start asking these kinds of questions, it is hard to stop. One of the things that art and geology have in common is that they are big disciplines, worthy of a lifetime of study. I would feel bad if I led any artist to neglect their brushes in order to study earth science. If you are too busy and you need to cut something out of the mix, dump television!

“Asilomar,” by J. Brad Holt, Asilomar, 2015, oil, 12 x 12 in.

So what are rocks made of? The answer is minerals, which are defined as naturally occurring inorganic solids possessing an orderly crystalline structure and a well-defined chemical composition. In terms of basic elements, rocks are composed principally of oxygen and silicon, followed by aluminum, iron, calcium, sodium, magnesium, and potassium. All of the other elements make up less than 2 percent of the earth’s crust. The bulk of the rocks that we see are silicates, which means that they are composed of silicon-oxygen tetrahedron ions. These tetrads combine with each other, and with other elements, in a variety of ways to form almost all of the rocks and soils on the planet. The non-silicate mineral groups include carbonates, halides, oxides, sulfides, sulfates, and native elements.

“Cedar Canyon,” by J. Brad Holt, 2014, oil, 12 x 12 in.

Rocks are classified into three major groups, according to how they were formed: igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary. Igneous rocks were formed through the cooling and crystallization of molten rock. There are two main categories of igneous rocks: intrusive and extrusive. When a magma body cools and crystallizes deep in the earth, it is considered intrusive. Extrusive rock is the product of volcanism, where lavas pour out onto the surface of the earth. Examples of intrusive rocks include granites and gabbros. Common extrusives are rhyolite and basalt. When rock at depth is subjected to heat, pressure, differential stress, or chemically active fluids, it may undergo fundamental changes. The resulting rock is considered to be metamorphic. In this way shale may become slate or schist, granite may become gneiss, sandstone may become quartzite, and limestone may become marble. Sedimentary rocks are composed of rock grains that have been weathered and redeposited through the action of wind, water, and gravity. Common sedimentary rock types include shale and mudstone, sandstone and conglomerate, as well as limestone and dolomite.

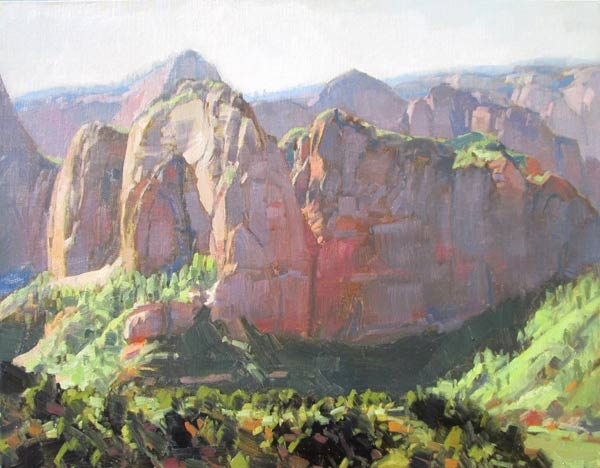

“Pine Valley Mountains,” by J. Brad Holt, 2015, oil, 9 x 12 in.

To answer the question of how the rocks came to be where they are, we must get into plate tectonics, which I would like to examine in a future article. For now, suffice it to say that the earth is a dynamic system. The crust is in constant motion. The rock that seems timeless wears away to be re-deposited, or is eventually subducted back into the mantle, to be reborn in fire. While the earth is 4 and 1/2 billion years old, the oldest rock discovered (in Northwest Territories, Canada), is around 4 billion years old, and this is rare. Most old rock is less than half that age, the bulk of it having been worn away or consumed in fire. This rock cycle is one of many interlocking systems and cycles that add up to a very active planet. The timeless appearance of the earth is an illusion imparted by the fleeting nature of our lives.

I love Jim McVicker’s work and love talking painting with him. He deserves every bit of success he has gotten and is an on-going inspiration to the rest of us Humboldt County artists!

Like your work. Especially the first piece. It is hard to get the cools to tell without the warms. More iron- bearing rock locations and /or more sunny evenings. Regards , Thom

Good first piece. The excitement of warm against cool. Regards, Thom