By Anne Dinkelspiel, Ph.D.

“This painting is awful!” “I can’t paint!” “This is hopeless!” You probably haven’t heard comments like these coming from your teacher or fellow painters. But you might have heard similar messages in your own head. This is the voice of the “inner critic,” and we all have one. Left unchecked, this critical inner voice can wreak havoc in our lives and in our art. But once it’s recognized and tamed, we can begin to experience more joy and creativity in our painting.

I loved to paint when I was in high school. I would spend countless hours in the studio. It was like heaven for the budding artist in me. I started college at UC Davis because the famous artists Wayne Thiebaud and Robert Arneson taught there. But instead of joyfully jumping into art classes, it took me 45 years to take another painting class.

What happened to that budding artist who loved to paint? In retrospect, I can see that the inner critic sabotaged me and stopped me from painting. My inner (art) critic told me that I was not good enough to take a college-level art class, that if I wasn’t Monet, Manet, or Matisse, there was no point in pursuing my interest. That harsh, critical voice told me that it would be humiliating to even try to paint. That mean inner critic kept me from something I loved: painting.

This is the power of the inner critic: It can interfere, interrupt, or completely shut down our creative pursuits as well as adversely impact other areas of our lives. My inner critic shut down my creative process — but not completely. Apparently, doodling during lectures or illustrating the dreams I wrote in my journal were safe from the judgment of my inner critic. My inner critic wasn’t going to attack as long as I did not think of it as art that others would see.

The good news is that while I was doodling during lectures and painting my dreams, I was also getting a doctorate in clinical psychology. Over the decades of practice as a psychologist, listening to hundreds of people discussing their lives, I realized that self-criticism is often at the heart of people’s suffering. The more harsh a person’s inner critic, the more trouble it can cause. In the extreme, it can even lead to crippling anxiety and depression.

We develop inner critics as we internalize the messages we hear as children about what is “good” and what is “bad.” This extends into almost all areas of our lives. With regard to our artistic pursuits, our finger paintings are probably all good as long as we aren’t eating the paint. But as we get older, the critiques start piling on about what is a “good” and what is a “bad” painting.

I remember teaching art at summer camp. The kindergartners were joyful and enthusiastic as they played with their paint. They loved everything they did. But by the time many of the kids were in middle school, a good deal of the joy had been sucked out of their creative pursuits. Art time at camp was deliberately designed NOT to depend on great skill but the 12-year-olds were grimly declaring “I’m not very good at art” as they made leaf rubbings, which the 5-year-olds had just created with delight.

We internalize messages from our parents about what is “good” and “bad” in an attempt to protect ourselves from embarrassment or shame. In order to avoid Mom/Dad/teacher telling us something we did was bad, we give ourselves the message and attempt to elicit the pride and approval of our parents or teachers. We criticize ourselves before anyone else has a chance to do it “to” us. Those middle school kids at camp were doing a great job beating everyone else to the punch. And our inner critics can be so harsh that we can find ourselves frozen with anxiety, doubt, and the very shame that we were trying to avoid. In the extreme, it can lead us to a fear of failure that can leave us paralyzed. Hence the 45 years without a painting class.

The inner critic can come in the form of blatantly cruel self-talk: “I’m horrible at this. I can’t paint. This painting sucks.” But the inner critic can also take a more subtle form. I like to call it the “stealth mode” of the inner critic. It might even sound like it is trying to be helpful as it points out all the things that are wrong with your painting. It might sound something like: “The perspective is off. That color is not right. This rock looks like it might float away.” Sometimes comments like that are actually helpful but if the inner critic is present, you won’t feel happily inspired to fix the problem. Instead, you will feel deflated, discouraged, and even ashamed.

Some people will insist that without their inner critic, they cannot learn or improve their paintings. But I would argue that there is a distinction between an inner critic who leaves us feeling deflated and discouraged and a kind inner art teacher who is supportive and encouraging while providing us with ways to improve a painting. It is this kind, inner art teacher who helps us learn from our mistakes and hopefully has a sense of humor!

When we have cultivated a kind and compassionate inner voice, then we don’t have to worry so much about being a failure because we can trust we won’t attack ourselves in the process. I had done a lot of preliminary work on silencing my inner critic and cultivating an attitude of self-compassion when a friend told me about the painting classes she was taking at a local art studio and suggested I join her. I happily signed up.

I remember the delight and excitement I had the evening I attended my first painting class in 45 years. I was even more delighted when the teacher said that the most important thing was to have fun. And fun it was (at least for me!). But I did notice that some of the other students in the painting class were being attacked by their inner critics. They were harshly criticizing their own work and comparing themselves with others. My heart went out to them because I know how painful it can be. I began to think about how to apply the clinical work I do helping people with their inner critics to the context of painting.

Here are some suggestions for taming the inner (art) critic and cultivating a more supportive inner voice:

1. When you identify those critical thoughts running through your mind, name the inner critic as their source. And since you are an artist, you might even want to imagine what your inner critic looks like. Perhaps you’d like to paint him or her. Use humor! It can be disarming.

2. Say “no” to the inner critic. Stop the critical thoughts. Acknowledge that the self-criticism is causing suffering and is not helpful. Again, you might want to use visualization or illustration to imagine a way to protect yourself from the destructive criticism. Perhaps you can imagine a wall around the inner critic or your inner critic in the middle of the sea. Illustrate it!

3. When you catch yourself with the negative commentary, try to replace it with more supportive and compassionate messages. Cultivate the kind inner art teacher. Maybe you have even had a real live external art teacher who was able to deliver instruction and point out areas that needed work in a way that left you feeling encouraged and inspired. By all means use this person as your model for how to talk to yourself! Internalize their manner. Another way to access a kinder and more supportive inner voice is to imagine what you might say to your dearest friend whose painting has areas that could be improved. And once again, visualization and illustration can be powerful tools.

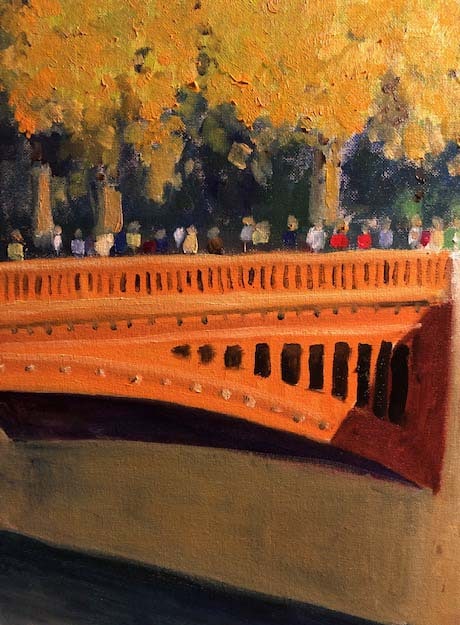

4. Remind yourself that not every painting is going to be a masterpiece. If it doesn’t have to be a masterpiece, then you can relax, and your inner critic can relax and stop harassing you. One of the most helpful classes I took was called Paint Sketching. We were on a one-hour timer. If my inner critic started up, I would tell her that I was on a timer and didn’t have time to listen to her criticisms because I had to keep painting. I painted on cardboard because I didn’t expect to create anything I’d want to keep. But the paintings from that class are actually some of my favorites. I loosened up and had fun. It goes to show that the inner critic is really not helpful to the process of painting! You will not produce better paintings by being mean to yourself.

5. When someone compliments you on your painting, take it in! Do not allow your inner critic to point out all the things you think are wrong. Just say thank you. Allow yourself to enjoy the compliment. See if you can find things you like in your painting.

6. Remember painting should be fun! The inner critic is NOT fun. It’s a surefire killjoy. Come back to what you find fun about the process of painting. Look for what you enjoy. If you are having fun, the inner critic is probably nowhere to be found.

Dennis Perrin, a wonderful painter writes, “As I am now in my fourth decade of painting professionally, I can honestly say that the most important lesson I have learned is that it has to be fun. I don’t do anything that’s not fun for me, even challenging activities like painting . . . One of the wisest things I ever heard was there can be no happy ending from an unhappy journey . . . I start every painting with the absolute knowing that this is going to be fun, and what do you know? It always is!”

It is my hope that painting can always be fun for you, too. Perhaps some of these suggestions will make that more possible by helping you identify and learn to tame your inner (art) critic.

How do you tame your inner critic? Share it with us in the comments below!

Anne Dinkelspiel, Ph.D. is a psychologist practicing in Berkeley, California. She is also an artist, working mostly in oils. She is having fun painting and helping people silence their inner critics, particularly their inner art critics. You can contact her via her website: www.annedinkelspiel.com or see her paintings on Instagram at @annedinkelspiel.

***

Have you had your Sunday Coffee with Eric Rhoads? Check out his inspiring weekly blog, where he talks about art and life, at CoffeeWithEric.com.

And browse more free articles here at OutdoorPainter.com

I find myself enjoying the bonus of low expectations and then the great thrill and surprise when it turns out just lovely

😀 That works, too!

I frequently repeat the adage to myself and others that each painting is practice for the next one. Also that practice promises improvement, but that your painting is guaranteed not to improve without practice. Looking at art in books as part of my teaching, I remind students that, yes, even acclaimed artists have bad days. Just because a painting gets into a book doesn’t make it a masterpiece. I remind my students that their gifts and skills are unique, that their guide to individual style is often to be found in their own likes and dislikes. Rather than wanting them to copy someone else’s style, I want them to question themselves after each painting and to see paintings as stepping stones in their progress. What do I like or not like about this painting? How will this self-critique or gut feeling help with the next painting? Usually our own answers end up reinforcing the fundamentals and ideas about direction. Not everyone is great with color or composition or whatever. But every artist has some talent or skill that with nurturing development makes the effort satisfying and worthwhile. As with any other type of communication, through experience we bring our art in sync with what it is that we want to say.

Beautifully said!

You are exactly right – took me 62 years to figure it out! Thank you!

I have been drawing and painting for about 75 years now and this is great advice..I remember that I thought every painting had to be great..the harder I tried the more miserable I became! Once I let go of all of that..I started doing better paintings and had a lot more fun! Often we can have these core beliefs..as having to be perfect…can’t make mistakes or fail…we get those from often irrational ideas from childhood..therapy has helped me a great deal…we just have to be open to that kind of thing..it just might be the bet investment one will ever make!

Wonderful Peggy… your students are so lucky to have you!

[…] California psychologist, and an oil painter. This week, she posted a thought provoking essay on Six Ways to Silence Your Inner Critic. If you’ve been nagged about your art by that ill-tempered little booger residing in your own […]

[…] in the world. But if you want to have a rewarding experience at the workshop, you’ll need to ignore your inner critic. You might not get everything right the first time—but allowing yourself to make mistakes will […]

Ref: Citrus in Light—-shadows have color. They are not black, gray, or brown. Study the paintings of Henry Hensche.

I’ve been teaching an Art & Psychology Visualization Workshop en plein air on Monhegan Island in Maine since 2022 with a clinical Psychologist.

It’s exactly that inner critic that limits our growth. The beliefs can be inherited going back generations.

There was story of a newlywed making a roast to impress her new husband. The roast was pricey and the husband asked why she had cut off and discarded some of it.

She replied, that’s the way her mother always did it.

He persisted and she called her mother to ask why she cut off the ends and the mother replied that it was the way her mother prepared it. The newlywed’s mother called her mother to ask why she did it that way. Her answer was ‘ I didn’t have a pan big enough’.

We often do things without questioning because, it’s always been done that way.

In dealing with my inner critic, I get the little bastard drunk and when he passes out I get some of my best work done. Then, the next day when he wakes up, he’s usually so hung over he can’t think straight and I tell him all the great things I’ve painted so he better keep quiet.

While I once thought it would take a baseball bat to cream the inner critic, all it took is hard and constant work, working on several paintings at once, and ignoring any idea of competing. I learned to keep painting no matter what.