A wild animal won’t sit still for a portrait, but many of the best wildlife artists nevertheless do their most important work en plein air, from life. A show at Flinn Gallery in Greenwich, Connecticut, explores the key link between field studies and the studio paintings of wildlife artists.

“Wildlife Art: Field to Studio—Revealing the (Field) Art Behind the Art” brings together the on-site preparatory work and finished pieces of seven signature members of the Society of Animal Artists, revealing their working processes to viewers and collectors. Susan Fox, Sean Murtha, Alison Nicholls, David Rankin, Karryl, Kelly Singleton, and Carel Brest van Kempen are in the spotlight for this show, which will be on view from March 24 to May 4.

“Periwinkle Flats,” by Sean Murtha, oil, 14 x 22 in.

The exhibition was long in the making. Susan Fox first thought of the idea in 2011, and she sent letters to artists in the animal art world who she thought would be a good match for a field studies/studio work show. “It’s a really great group of friends and colleagues,” says Fox. “What ties us all together is we all go out and create reference work in the field, and I think that brings something special to animal art.” The show’s development went in fits and starts, and then Nicholls got involved, lined up the gallery, and worked the logistics into order.

“Orange-Breasted Falcon and Granada Morpho,” by Carel Brest van Kempen, acrylic on illustration board, 24 x 18 in.

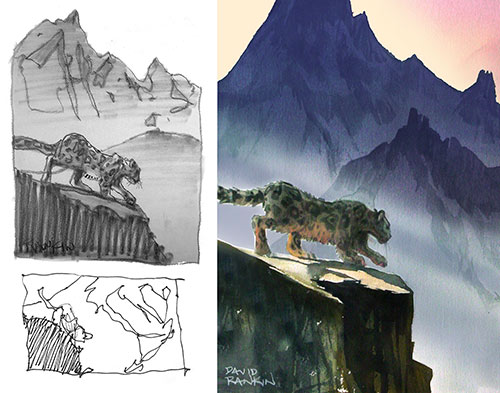

Rankin says he was pleased to take part in the exhibition because the concept resonates with him. “To me, it is the field work where most of my best paintings originate,” Rankin says. “I began working like this back in 1970, on my very first trip to India. My basic working method begins with my direct observations of subjects in the field, working directly from nature. I develop ideas in a number of different ways. Sometimes these are simple sketches in my sketchbook using a 9B woodless graphite pencil. But in recent years I have supplemented my working method with full-color sketches and studies that I create in a digital medium using my Apple iPad and an app called Paper by 53. This is how ideas and observations begin. From there I go on to use small quick watercolor studies in my sketchbook. And these lead directly to my plein air watercolors on Arches 140-lb. watercolor paper blocks.”

David Rankin’s graphite sketches and a watercolor study done on location in Kashmir

Their methods vary. Some work to make finished pieces in the field, complete in their own right. Some draw in sketchbooks. One of the participating artists sculpts in the field. The common thread for this group is a dedication to direct observation. “There’s no substitute if you want to present the animal with accuracy in terms of habitat and behavior,” says Fox. “There is a long tradition of artists working in the field. This is part of that historic tradition.”

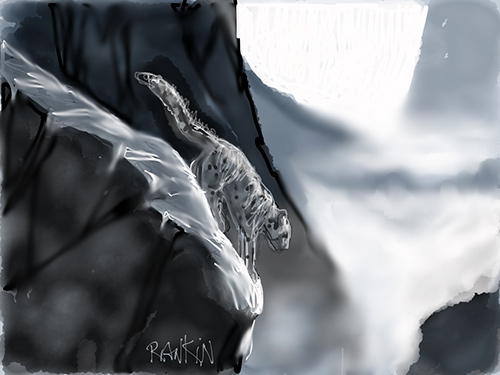

Rankin researched the subject further via sketches of a snow leopard at the

Cleveland Metroparks Zoo done on his iPad.

“Launch Pad,” by David Rankin, watercolor

Nicholls says the field studies are crucial for informing all her animal art, but she sees her work on-site and her studio pieces as two very separate endeavors. “My field sketching has taught me a lot about the anatomy and behavior of the wildlife,” says the Port Chester, New York, artist. “But I think of them as two different disciplines. In the field I can’t compose like I can in the studio. I am sketching what I see. The field sketch is likely to be more detailed — I really like to eliminate any unnecessary details in my studio paintings. In the field I am trying to achieve a finished sketch, but not to the same level of composition as in the studio.

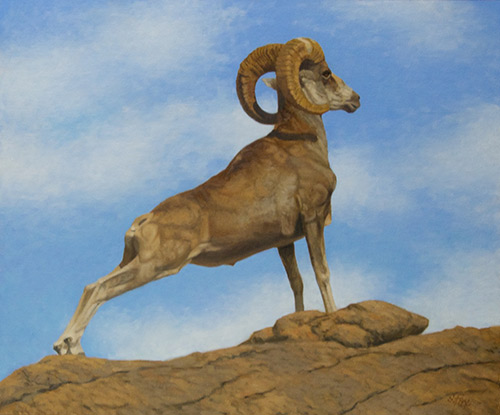

“A Good Stretch,” by Susan Fox, oil, 20 x 24 in.

“Playtime,” by Alison Nicholls, acrylic, 24 x 30 in. Studio piece

“The field paintings are watercolor, and usually 11” x 14”. In the studio I work larger, and with fluid acrylics on canvas. I don’t rely on photos or video to compose my studio pieces; they are very much informed by the sketching in the field. I will look through my field sketches, and I don’t necessarily turn one into a studio painting, but something that catches my eye about a field sketch will be come part of a larger painting.”

“Playtime,” by Alison Nicholls, watercolor, 11 x 14 in. Plein air painting of wild dogs that

inspired the acrylic studio piece

“Despite varied backgrounds, the participating artists are united by the unique theme of the show — their reliance on direct observation of animal subjects in the field,” the gallery’s press release reads. “‘Wildlife Art: Field to Studio’ acknowledges the overarching importance of field work and how it directly influences studio work by exhibiting examples of both disciplines together.”

“Sundown,” by Karryl, bronze, 14” high, 15” long, 9” wide

If it takes plein air painting skills to be a top-notch animal artist, it also takes a different mindset. As Fox puts it, “Painting a landscape, you are chasing light. Animal artists are chasing bears.”

For more information, visit the gallery’s website.