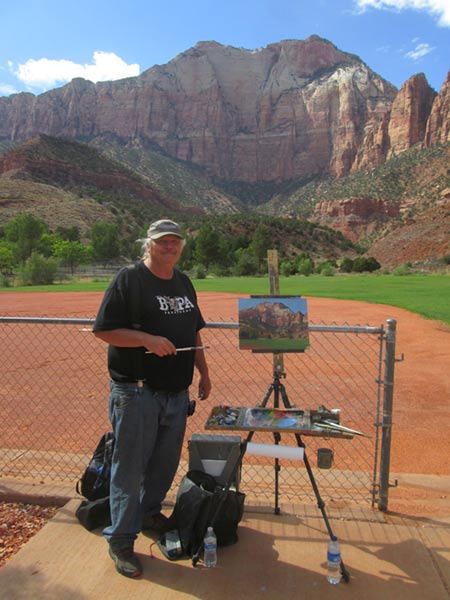

In this series of articles, Utah artist J. Brad Holt talks about what artists are seeing as they look at the landscape. Holt studied geology in college and is attentive to what the rocks suggest in the scenes he paints.

The recent celebration of Independence Day got me thinking about history. What we mean under the blanket term of history is, for the most part, political history. That’s normal. We tend to dwell upon those matters that most have an effect on our daily lives. But that changes if we narrow our focus to look at what interests artists in particular. Though we are still interested in political history, other types of history assume greater precedence, including the history of culture and technology. I think that artists are also very interested in natural history. With that in mind, I would like to offer a very brief natural history of North America.

During the last half of the Precambrian Era, about one billion years ago, the supercontinent of Rodinia formed, with the precursor to North America at its heart. It began to break up around 800 million years ago, and at the end of the Precambrian, many of the continents joined together in the southern hemisphere to form another supercontinent called Gondwana. North America, Siberia, and Europe remained apart. By the beginning of the Cambrian period, 542 million years ago, America, Europe, and Siberia began to join together to form a supercontinent called Laurasia, which was situated on the equator, and warm, moist conditions led to vast swamps that would eventually turn into the great coal reserves of America and Europe. Meanwhile, Gondwana drifted northward until, by the end of the Paleozoic Era, it collided with Laurasia to form the great supercontinent of Pangaea. At this time the collision of Siberia and Europe created the Ural Mountains, while on the western side of Europe, the closing of the Proto-Atlantic resulted in the Caledonian-Appalachian chain beginning to form.

The Mesozoic Era begins with the Triassic Period. Much of North America was landlocked, and desert conditions prevailed. Non-marine sediments laid down in arid conditions tend to be rich in iron oxides, hence the Triassic “Redbeds” in western North America, and throughout the world. The Jurassic Period saw the encroachment of shallow seas in North America, the vast dune deposits of the Navajo sandstone, and the rich fossil deposits of the Morrison Formation. Plant and animal life flourished through the Cretaceous Period, which marks the great coal deposits of the American West. The subduction of the Farallon Plate began adding new terrane to the western coast, and widespread volcanism created vast basalt deposits in western North America. Granitic intrusions in the Sierras and the northern Rockies also were emplaced at this time. It was a time of compression in the northwest, and the over-thrust of younger sediments, from west to east, occurred from Wyoming to Alaska. By the end of the Mesozoic, the Laramide Orogeny, which formed the Front Range and the Sangre de Christo mountains, had begun.

The beginning of the Cenozoic saw the once mighty Appalachians eroded almost away. The sediments from this would become the Atlantic coastal plain. A great geosyncline around the Gulf Coast also continued through this time. Eventually, numerous faults developed through crustal deformation, which caused petroleum to be trapped between non-permeable layers of sediment. Isostatic rebound helped to uplift the Appalachian region again. During the Miocene Epoch, tensional forces began to pull apart the interior west from Nevada to Mexico, creating the hundreds of block-faulted mountain ranges known as the Basin and Range province. Great outpourings of basaltic lavas occurred on the Columbia River Plateau, and the chain of strato-volcanos to the west became the Cascades. Uplift of the southern Rockies and the Colorado Plateau began at this time, and continues. This caused established rivers, such as the Colorado, to begin down-cutting within their own meanders. The earlier subduction of the East Pacific Rise, and the subsequent rifting and formation of major transform faults, began to tear Baja and western California to the north. Major faulting episodes during the late Tertiary finished some of the most beautiful and imposing mountain ranges of North America, including the Sierras and the Tetons.

So far, I have concentrated on the tectonic, and orogenic history of the North American Plate. Next time I want to give a brief history of the evolution of life in this region, and around the world.

Wow. billions of years of movement and earth evolution condensed into an essay on geology. I liked and appreciated Brad’s efforts and thoughts. I would love to have an afternoon conversation with him over a early Miocene Epoch gluten free beer.

Thank You

Fred Gregory

Really, really gorgeous job you did on your “Surf Near Point Lobos” painting, Brad ! …. as well as your rock paintings….but you know that I love those. See you in the fall, Rosie

Most impressive, Brad. Do you give workshops?

My husband is also a geologist and therefore we have visited many beautiful spots. Many of my paintings are from pictures he has taken. I love the insights he gives me regarding the rocks, formations and mountains we visit. I love your work!