Working quickly and directly, Joseph Zbukvic exploits all the qualities that make plein air painting with watercolor so unique.

By John A. Parks

Some of the greatest challenges for a plein air painter are to actually capture all that open air, the fresh play of light through the atmosphere, and the sense of shimmer and action we feel outdoors when breezes, sunshine, trees, plants, and people are all on the move. Australian painter Joseph Zbukvic seems to pull off this improbable feat, conjuring atmosphere, light, and movement through lively brushwork and adventurous use of all the drama that watercolor affords.

Underpinned by sure draftsmanship, his brush is set free to make confident marks that range from broad strokes to delicate skittering dashes. Meanwhile the watercolor flows, floods, and drips to soften edges and bring about intriguing passages of close color. His subjects are varied. Paintings of his hometown of Melbourne and its surrounds evoke a dusty Australian light, where buildings or distant hills shimmer in the haze.

In travel paintings from around the world, we find similar dramas — crowds on the move in Italian squares or the bustle of a sunny street in Barcelona. The paintings deliver a sense of a complete view while at the same time appearing utterly spontaneous and direct. “What I try to get is an illusion of a fleeting moment,” says the artist, “something like a small time capsule, the feeling that you have when you’ve just turned your head and glanced at a view rather than something that you have stopped and stared at for a long time.”

To get this feeling, Zbukvic works at great speed, taking advantage of the directness of his medium. “I can do three or four paintings in a day — sometimes more,” he says. “I rarely spend more than an hour on one painting. If I fiddle with it more than that, I’m going to kill it.” The artist says he will sometimes make tiny adjustments to a picture when he’s back in the studio, but in general he prizes the spontaneity and directness that comes from working in the field. Such an approach naturally means that the painting must work by suggestion and inference rather than with fully rendered forms.

“By flickering things on and leaving things half-finished, I get that fleeting-moment look,” he says. “If I define everything, it becomes boring. There’s nothing more boring than a perfect circle, but if you make some dots in a broken circle, your eye will be drawn to it to complete it. It’s an optical illusion.” The viewer is more engaged, says the artist, if things are suggested rather than completed by the painter.

FAVORABLE CONDITIONS

For all their sense of spontaneity and directness, Zbukvic’s watercolors are constructed with considerable thought and not a little planning. The first challenge is finding something to paint, and here the main consideration is often the light. “When I go out to paint, it’s usually to do with the weather,” he says. “If it’s a nice day, with a bit of haze and not too hot, I’ll be out there. It’s my number one rule. No matter how busy I am, if there’s a lovely quality of light, I’ll go out and paint.”

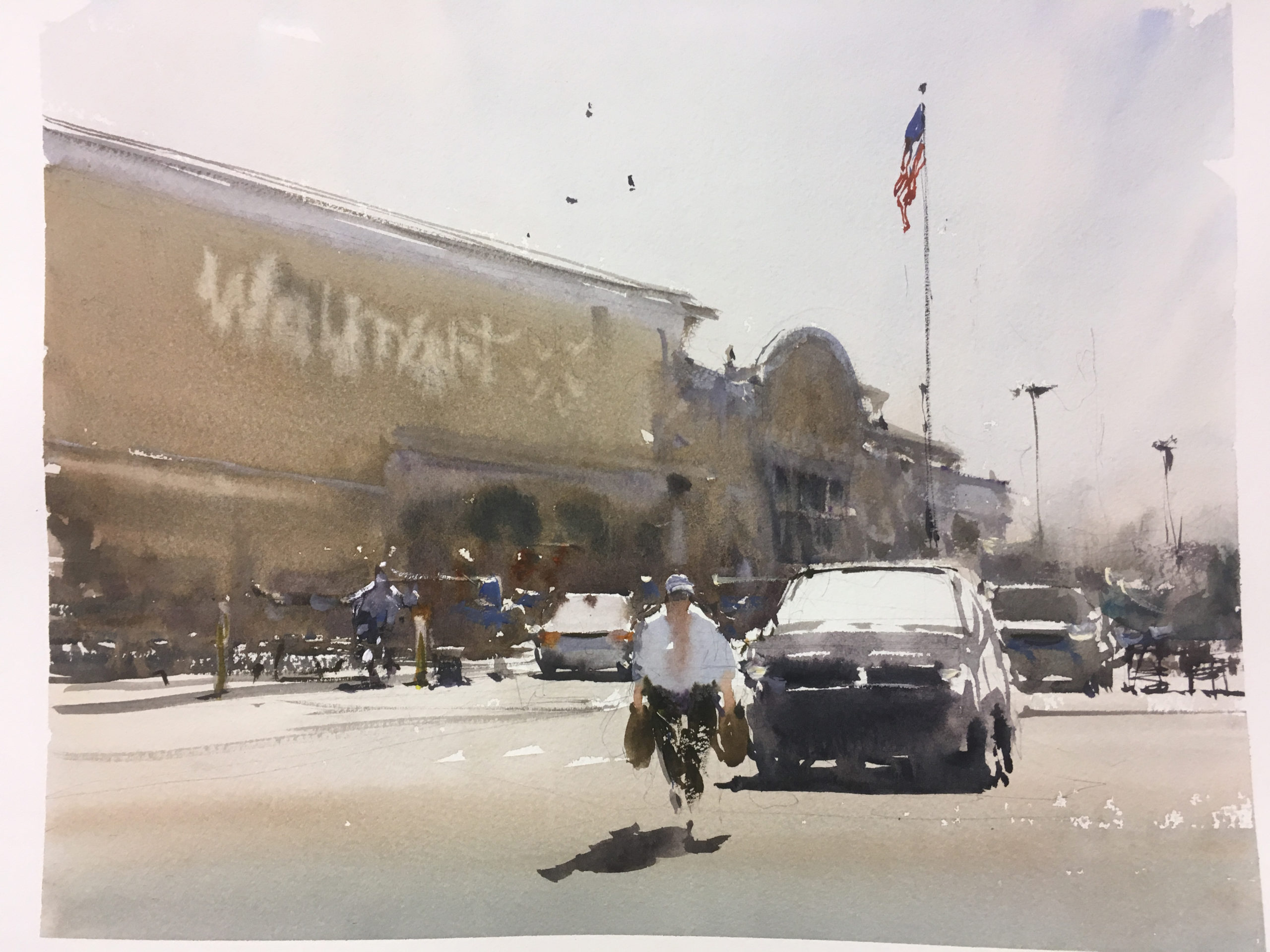

In choosing a subject, the artist says he is more interested in compositional possibilities than the idea of just painting a pretty place. “A lot of people think you need to go to a glamorous spot,” he says. “But for me it’s a matter of finding a good layout with interesting shapes and something that’s manageable in watercolor. I like painting into the light a lot — something that works perfectly in watercolor. If you paint with backlighting, then you get a lot of detail, and you don’t want to be out there for hours painting thousands of windows. I choose things that will be easily converted into my visual language, with big strong brushstrokes and quick execution.”

Apart from favorable lighting conditions, Zbukvic will also look for compositional possibilities. “Without a good composition, there is no decent painting,” he says. “That involves a good foreground, middle ground, and the layout of the shapes. People like to call it inspiration, but I just have this sort of vision of what the finished painting may look like. I can see it in my mind’s eye, and this makes it a lot easier to paint.”

DEVELOPING HEAVEN AND EARTH

Once he sets up to paint, Zbukvic launches directly into his painting. “Years ago I used to do thumbnail sketches,” he says, “but now I just see it.” He begins with one or two very thin washes. “It’s a two-step process,” he says.

“Firstly, I lay on a fairly faint wash of color that permeates through an area, usually a sky and a ground wash, which I call ‘heaven and earth.’ I let that dry, then place the major shapes on top of that wash, allowing it to show through. Say I’m out in the country, I’ll paint the sky down to the horizon with a faint blue and then I’ll paint a thin green over the fields, leaving some white areas for buildings or roads or whatever. For the second layer, I’ll come back around the buildings and develop the color.”

With a streetscape, the artist follows a similar attack, washing in the sky and road surface, and then placing cars, street furniture, and people on top of that. “I have to be careful to leave any whites that I need unpainted,” he says, “perhaps areas for roofs, windshields, or reflections. So I paint around them, making negative shapes. In the second layer, I come in with a stronger wash and then finish with the darkest of darks.”

The need to preserve white areas in watercolor paintings means that the artist must always plan ahead. “Watercolor is a strange process where quite often the major feature in the composition, let’s say it’s a ship at a dock, is the last thing to be put in the painting. First, I paint the background and foreground, and then get involved in that big shape last. I have to see things in my mind’s eye ahead of time and avoid doing things that will interfere with it. I can’t have lines, say a horizon line, running through elements that have to feel solid. Lines will always come through. So I’ve got to be very careful, there’s no going back.”

It’s a process Zbukvic likes to compare to performing surgery. “One wrong cut and the patient dies,” he says. “While the painting is wet, I can get a tissue and mop off the paint and get rid of it. Once it’s dry, then I have that edge, and there isn’t really a good way to get rid of it. Some people try scrubbing, but you can always see the damage. So painting in watercolor is a kind of strange dance between being a visionary and a romantic, and shooting for that feeling of spontaneity, while at the same time having to calculate everything and be technically perfect.”

EDGE MANIPULATION

One of the features that creates so much space in Zbukvic’s work is his use of a wide variety of edges, ranging from very soft to hard and crisp.

“Two of the most powerful weapons in your arsenal are tone and edges,” he says. “Only then comes color. Color is good for emotion, but to achieve reality you need tone and edges. If you look at a black-and-white photo, you will see both soft and hard edges. You can have a staccato painting that’s full of bristling sharp edges — say a construction site that’s full of cables and scaffolding, or you can have a subject dominated by soft edges — say a scene filled with morning mist. And then you can contrast sharp and soft edges. Really, if you’ve got a dead straight line, it’s very boring; it’s always better to break it up. On the other hand, it’s important not to have too many soft edges, or it will just look like a sopping mess.”

As well as creating space and air, Zbukvic points out that edges also reveal the kind of marks the painter is making. “Having some strong, sharp, but broken edges shows that you’ve painted fast and with a large stroke, leaving a dry brush mark,” he says. “The marks that you leave behind convey a subliminal message to the viewer. It shows confidence. The viewers don’t know necessarily that it’s a confident painting, but they can sense it. They can sense when it’s a nice positive brush mark that hasn’t been played with.”

CONNECTING TO SUBJECTS AND COLLECTORS

While Zbukvic concentrates on landscapes and cityscapes, his work also takes on a wide variety of other subjects. These include paintings of horses, and paintings of figures — usually working people, shown going about their tasks. “I grew up on a farm back in Yugoslavia,” explains the artist. “My grandparents kept a team of four draft horses to plough with and to move things around the farm. It was my job to bring them water, and I often helped harness them and sometimes rode them. I loved them, and I’ve loved horses ever since.”

The artist points out, however, that most of his paintings of horses are really paintings of the people working with them — jockeys or stable hands. In that sense, they are close to his paintings of working people. “I like to work with my hands myself,” says the artist. “I built a house in my younger days and I do all my own work on my cars, so I have a high respect for people who labor. I paint market themes or people working on farms, digging, or fishing. I love painting butchers working with their meat, although the subject is hard to sell.”

Having broached the subject of selling, the artist observes that most people who buy a painting do so because of their connection to the subject matter. “Some think that people buy paintings for technique — and that may be the case for photorealism — but most people buy because the image means something to them. They’ve been to that place for a vacation and had a good time, it’s where they had their honeymoon, or it evokes childhood memories — that kind of thing.”

On the other hand, Zbukvic says he never thinks about potential sales when he is out painting. “I couldn’t care less,” he says. “I never do commissions. Why would I want to have someone tell me what to paint? My philosophy about painting is incredibly simple. I just paint. As soon as I try to get too clever and paint because I think something will sell or win a prize, I find I come unstuck very quickly.”

Far more than the commercial success he enjoys, Zbukvic treasures the connections he makes with other people. He tells a story of how a man stopped him on the street while he was painting one day and told him he had saved his life. The spectacle of seeing Zbukvic at work on a painting out in the country some years before had inspired him to become an artist, and he was traveling the world making paintings. “I’ve also helped a lot of students and seen them take off and sometimes become teachers themselves,” says Zbukvic. “I get enormous satisfaction when I see people I’ve helped succeed.”

As for what his work brings to the world, Zbukvic says his paintings provide “quiet moments of joy.” He takes great pleasure in seeing people enjoy his work whether they buy it or not. “I don’t have any delusions,” he says. “I know I’m not going to change the world with my work. I’m not a Banksy or anything like it. I’m just a nice painter of watercolors. I just paint, and everything else comes after.”

Visit EricRhoads.com to find out all the amazing opportunities for artists through Streamline Publishing, including:

– Online art conferences such as Plein Air Live

– New video workshops for artists

– Incredible art retreats

– Educational and fun art conventions, and much more.

> Subscribe to Plein Air Today, a free newsletter for artists

> Subscribe to Plein Air Magazine so you never miss an issue