Susiehyer doesn’t have a set way of painting nocturnes. She has several, and the Colorado artist will be sharing them with participants at the Plein Air Convention & Expo (PACE) in April in San Diego.

The artist was scheduled to paint a demo onstage at last year’s convention, but she suffered an injury and had to stay home. This year, she’s ready to lead participants in painting scenes on two nights in San Diego after dark.

Susiehyer says she thinks the best approach on the first night will be to paint a demo before dark and help painters after dark. “The convention is in April; depending on where San Diego falls in the time zone, it will probably get dark around 7 or 7:30 p.m.,” says Susiehyer. “I will paint a demo while it’s light and show how the value system can be set up, and the methodology one can use for making nocturnes. When it gets dark, people can have the experience of painting in the dark with headlamps or booklights for palette and canvas. Things are different after dark because the painter has to adjust, let his or her eyes open up. Value differences get extremely tight. But some of the same things apply as when you are painting during the day.”

“Sleepless in Sedona,” by Susiehyer, oil on linen panel, 14 x 18 in.

The painter explains that there are several ways to skin this cat. But first, Susiehyer points out that when people talk about nocturnes, they are sometimes talking about three very different light conditions. Some artists block in the scene while it is still light, then add the light effects of sunset as they appear in the scene. Susiehyer says this will not work, as the big blocks of value completely flip during the course of twilight and night. In fact, twilight has its own value scheme, as does dark. The primary difference between these three states is the value range, but the darkening sky also means a flip-flop in what is the lightest element in a scene.

“Towers in the Night,” by Susiehyer, oil, 11 x 14 in.

“In daylight, the values are wide,” she says. “There are light areas and dark shadows. In twilight, the sky starts to get dark, but there is still light. The darker values are on the ground plane. The sky is a lighter value than the ground. But in full dark, the sky is dark, and the ground plane may end up being lighter than the sky. As darkness comes, the values of the big shapes, the big value groups that design your painting, shift and sometimes completely change. There are three completely different paintings.”

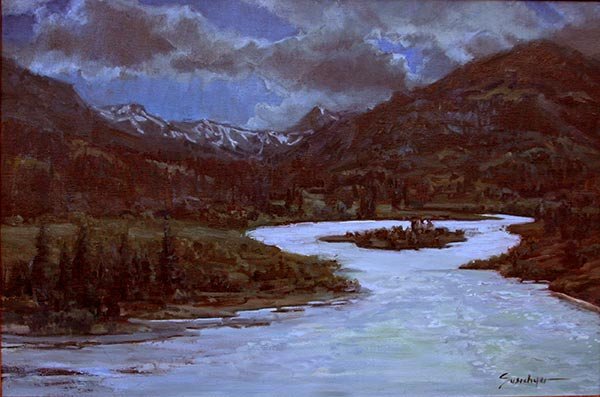

A 24 x 24 inch commission Susiehyer painted on birch panel

Susiehyer makes one interesting observation: Once the light is fading, vertical planes can be depicted as the darkest element in the painting.

“Darkness at the Edge of Town,” by Susiehyer, oil on Masonite, 12 x 16 in.

She plays around with nocturnes in other ways, such as using complementary palettes to make dramatic scenes. Focusing on utilizing dark blues and dark oranges makes for a powerful nocturne, for example. Susiehyer also advises mixing mother colors to unify a nocturne. This can mean mixing a mother color for the moonlight that one adds to all elements lit by the moon, and a sky color one adds to all colors depicting areas in shadow. The moonlight color may have cool yellow in it; the sky color, some purple.

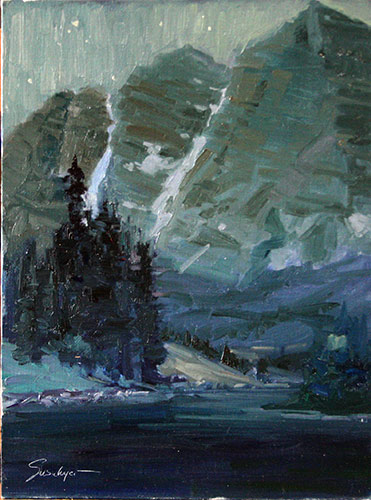

“Evening at Maroon Bells,” by Susiehyer, oil on linen, 16 x 12 in.

Susiehyer and her painting friends have one more approach to nocturnes: painting “dayturnes.”

“To some extent, you paint what you see during the day in a dayturne,” she says. “You use the same value range that you see during the day, but you transpose it to a darker key. You simply paint a low-key painting using the colors and temperatures that you may see at night. There are similarities. Both at night and in the day, the warmest values may be in the foreground, and you would push the colors cooler and grayer and lighter in the background. You just create the atmosphere of night in the dayturne.”

Regardless of how one chooses to approach a nocturne, an artist will have to embellish the scene. Painting a nocturne strictly the way our eyes see will likely result in a boring, dark piece. “Even in really bright moon, you don’t see colors and detail,” Susiehyer points out. “At night, all the edges are blurred and everything is muted. We have to portray the illusion that we are looking at something at night. People want some magic; really dark nocturnes won’t sell,” she adds with a laugh.