In this series of articles, Utah artist J. Brad Holt talks about what artists are seeing as they look at the landscape. Holt studied geology in college and is attentive to what the rocks suggest in the scenes he paints.

Of oxygen and iron I sing, and of the rusted skin of the earth, clad in sanguine raiment.

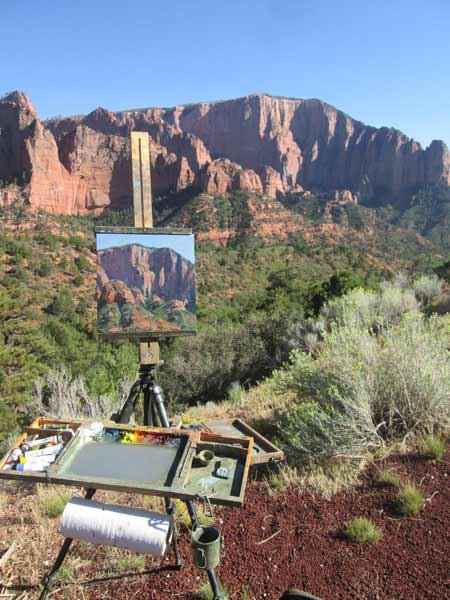

I am a red rock painter, perched here on the western edge of the Colorado Plateau. The land about me is an embarrassment of riches to an artist interested in the ruddy bloom of Mesozoic sediments. Of the five national parks in Southern Utah, four of them were established on Mesozoic red rock. There are red shales and clays, and conglomerates and mudstones, but most of all, there is sandstone, of every hue. We love how it breaks and weathers, and erodes in myriad fantastic forms. The playground of the imagination is furnished in multi-colored sandstone.

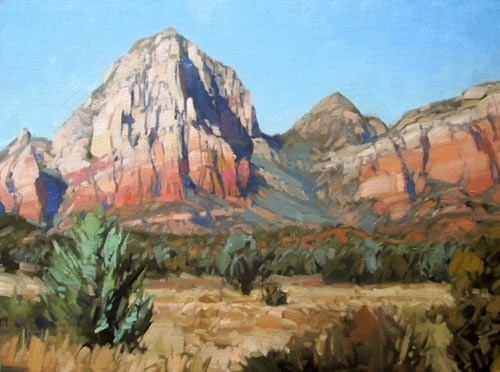

“The View From Moonlight Drive,” by J. Brad Holt, 2014, oil, 12 x 16 in.

But what is sandstone? Where did it come from? How was it formed? And what about sand itself? We understand that it is the product of the erosion of rock, sorted by action of wind and water, but there are so many kinds of rock. Why is sand so consistent in composition and form throughout the world?

The answer to these questions comes from an understanding of the nature of both chemical and mechanical weathering. In chemical weathering, complex processes break down minerals internally, and change their forms. Usually this is caused by dissolved carbon dioxide in groundwater, which gives it the properties of a weak acid. When granite is exposed to this carbonic acid for long periods of time, its feldspars are altered to produce clays, leaving the resistant quartz grains to become sand. Quartz is impervious to both chemical and mechanical weathering. It will be transported and sorted into riverbeds and beaches, or transported by wind to become dune deposits. Eventually, these deposits will become sandstones.

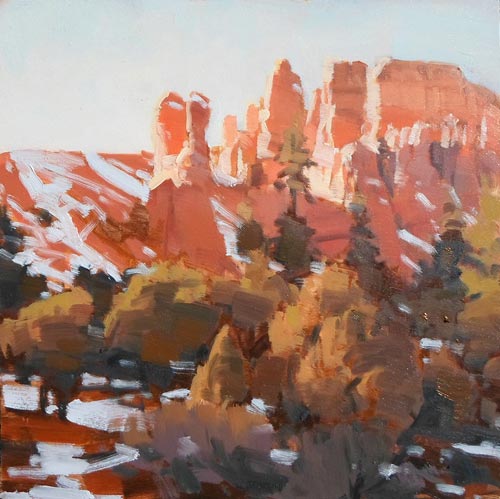

“Red Canyon Series VI,” by J. Brad Holt, 2013, oil, 8 x 8 in.

A small amount of dissolved silica is also produced by the chemical weathering of granite. This silica will be transported to the sea to be used by diatoms in the construction of their shells, or will precipitate out in the form of agate and chert. Other components of the granite, such as micas, olivines, amphiboles, and pyroxenes, will chemically weather into clays and iron oxides. These iron oxides will impart a red coloration to the sedimentary layers in which they are deposited.

Chemical and mechanical weathering act in concert to produce the outward form of rock that we find so interesting to paint. Rock weakened through chemical processes is more vulnerable to the action of wind and water. Differential weathering occurs as zones of weakness are eroded away to leave resistant monuments behind. Angular surfaces gradually become rounded as chemical weathering attacks the greatest amounts of surface area. As the weakened surfaces are spalled off, the character of the rock becomes rounded and smooth. These surfaces become fins, as joints in the rock structure allow penetration of acidic water and oxidizing air. Given time, these weathering processes can produce a fairyland of beautiful forms.

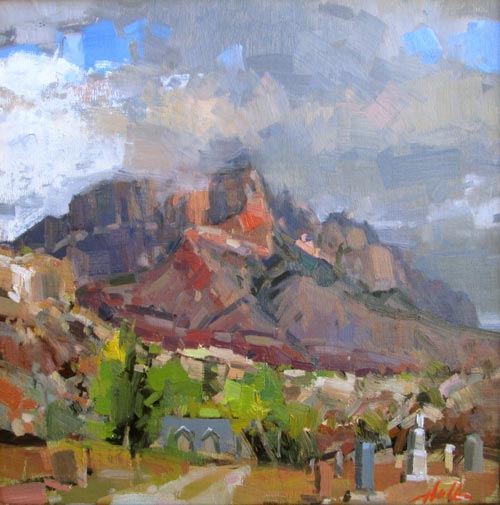

“Rockville Cemetery,” by J. Brad Holt, 2014, oil, 12 x 12 in.

The material produced through weathering and mass wasting usually moves only a short distance from where it originated to become an accumulation of rock fragments, sand particles, and clays that is called the regolith. True soils evolve above the regolith at various rates according to the climate and topography of the land. Soil is composed of mineral matter, air, water, and organic debris. There are usually distinct horizons present in mature soils. The top layer of true soil is followed by a zone of leaching, and a zone of accumulation, which is mostly clay. Below this is a zone where the regolith is evolving into soil. Soils are delicate, and vulnerable to disturbance and erosion. They take an immense amount of time to form, and must be conserved as a limited resource.

To witness the power of weathering for yourself, visit an old cemetery, and try to read the names and dates on the really old stones. Many of the early markers in my area were constructed of sandstone, and there is sometimes no trace of writing left on their weathered faces. It is also a good lesson in differential weathering, as you can note which types of stone seem to be most resistant. Beyond this, I find cemeteries are often nice places to set up an easel and paint.