– Bob Bahr reporting, Editor PleinAir Today –

California painter Catherine Fasciato likes to paint rocks, and she’s good at it. We asked her for advice on making rocks look convincing in a painting. Here’s what she said.

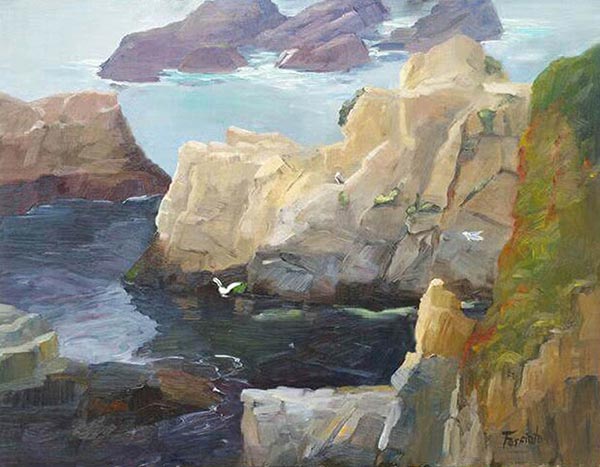

Lead Image: “Around and Around,” by Catherine Fasciato, 2016, oil, 14 x 18 in. Collection of Ann Hobson.

Fasciato first reminded us of the basics. Rocks are solid. They are often sharp. The painter has to allow for these two things to show through in the painting. “First, make it a mass, and simplify it,” she says. “Rocks can be very complicated, but you have to start by finding two values — the lightest light and the darkest dark — and getting the basic form down. Determine where the light source is, get the values, and work from there.”

The artist says it’s also important to remember that rocks cast shadows. These shadows help anchor the rock. Fasciato says she often remembers what she heard Don Demers say about painting scenes such as this: Spend an hour or so just looking. See how the rocks and water are interacting. Note where the light is coming from. If the light is facing the rock, you don’t get a reflection, just a flat color.

She points out that while the shadow should be stated at the same time the rock is blocked in, the process diverges from there, depending on whether the rock is in water or on sand or land. If the rock’s shadow is hitting sand or land, then the earliest statement of the shadow can stay almost untouched. If the shadow is in the water, then the artist will likely have to restate the shadow as the colors in the water are worked over. Also, “Put the part of the rock that you can see underneath the surface first, then put what is on top of the water after,” Fasciato says. “Put those darks in first, while you are putting the rock in.” This also helps to firmly anchor the rock.

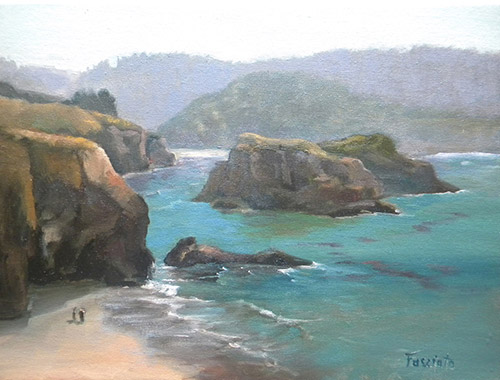

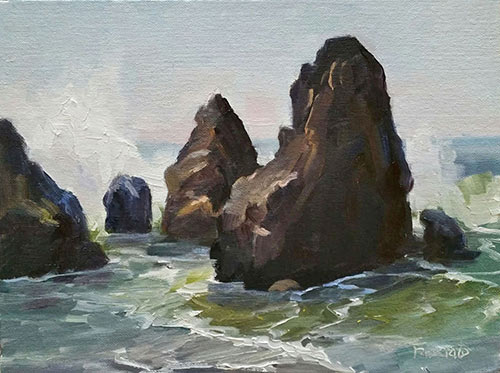

As anyone who has tried to tackle rocks — especially coastline rocks — knows, there is great color variation in them. Fasciato says that one tip is to consider the color of the sand, as the sand is often made up of pulverized rocks from the area. Still, there will be striking blond rocks, like in Carmel, California, and brooding dark rocks, like just down the coast in Big Sur. As in most situations, value is more important than color. “Block in the basic color, then play around with whatever color looks good in the picture,” says Fasciato. “You’ll see pinks and purples in a lot of rocks. There will be greens and blues. After the basic block-in I look to see the underlying colors in the rocks.”

Flat brushes help to give craggy rocks the appropriately sharp edges and planes. Fasciato proclaims a special love for backlit rocks, which allow her to paint a sort of warm halo around them. In general, she enjoys putting rocks in her paintings, and it shows.

“I think rocks can be very important to a painting,” she says. “They provide solidity, darkness, interest. And sometimes the light hitting the rocks or hitting the side of a cliff adds such a beautiful point of interest. Somebody once called it ‘bling on the rocks.’”