The three pieces Sally Loughridge decided to talk about for this article were all done by friends. That suggests she chose them based on familiarity, or a shared experience. But listening to her, we hear a third reason for their inclusion in this artist’s collection.

All three exhibit risk-taking in one way or another.

The first piece, by Ann Sklar, is essentially abstract. “She used to do much more realistic, representational work,” says Loughridge. “In her new ones, virtually all have a horizon line; in some, that line is harder and more apparent than in others. It’s the simplicity and the colors that appealed to me. I’m always looking for ways to get simpler in my work. I read the reflective quality of water in the foreground — maybe this isn’t water, but it’s what it says to me. The palette choice might be considered complementary if you see it as red and green, as I do. My goal is not to paint like Ann, but to paint like me. But I do like simplifying, and I find power in it.”

“Cottage on the River,” by Audrey Bechler, acrylic, 12 x 24 in. Collection of Sally Loughridge

Next up is “Cottage on the River.” “I think I was drawn to Audrey Bechler’s piece because it was ‘long skinny’ — the elongated rectangle, which carries with it some unique challenges in terms of composition,” says Loughridge. “In this piece, you can travel the waterway all the way back to the tree stand.” Loughridge says the painting rewards close scrutiny. “Her brushstrokes are loose and you can see how she applied the paint, and I like that too.” The subject matter appeals as well, but more on that later. Loughridge says the overall mood is enticing — and also reflective of Bechler’s personality. “There’s a sense of tranquility to it, a peacefulness,” says the Maine artist.

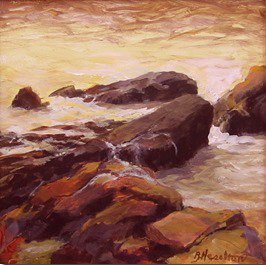

“Surf,” by Betty Heselton, acrylic, 12 x 12 in. Collection of Sally Loughridge

All three of Loughridge’s selections were trades. Loughridge enjoys painting with friends, and she goes to Monhegan Island with Betty Heselton and other women each year. Heselton’s “Surf” is the last piece Loughridge discussed. “I don’t know if this one was painted en plein air — she has the capacity to generate something like this from her imagination,” says Loughridge. “I love the golden color. I like the analogous colors, the narrow band of color choices. She was not afraid of making a lot of the water be yellow, and to put a lot of color in the rocks. Heselton had a solo show in Rockland, Maine, that I saw last summer, and over the years, I have seen several hundred of her paintings, and I’ve painted with her for days on end, but I like this one especially.” Another reason she likes “Surf” is its square format. “There’s no automatic tension set up or built in with that format,” says Loughridge. “With equal sides, it’s up to you to create that positive tension. You can make a square look vertical or horizontal, and to me, that makes it fun.” Loughridge also points out that the rocks form “a little pool or harbor that holds you in the painting, keeps you from going out.”

So each piece, in its own way, took a chance, be it going abstract, using challenging color, exploring an unconventional format, or arranging organic elements to design a captivating composition. All three have something else in common: The subject matter suggests the coast.

“Manana, Shimmer and Shadow,” by Sally Loughridge, pastel on panel, 12 x 12 in.

“I particularly enjoy the meeting of the land and the water, that edge there,” Loughridge acknowledges. “I like the transitional areas where land meets sea. Rocks are pretty hard; they are the stable, organic characteristics of land masses. Water gently touches the land, or crashes against it as surf. It’s the notion of soft against hard, liquid against form. These elements are very different, and yet they are in touch with each other. There’s a lot of appeal to the way the land and water meet. Sometimes it’s a caress or embrace, sometimes a fierce meeting.”

Loughridge spent years as a clinical psychologist, so these descriptors seem to suggest that she sees the elements of a coast as a metaphor for human relationships. “Yes, maybe,” she laughs, “but I try to paint while being informed or excited by my emotion to something. Afterward I may ask myself why something appeals to me so much. But I don’t want it to get overworked. I know it affects my art, but I am trying to balance it all, in terms of balancing right and left brain.”