By Lori Putnam

Over the next few months, artist Lori Putnam will occasionally speak on the role artists can play in the conservation and preservation of land and buildings. In this first installment, Putnam addresses oyster restoration in Apalachicola, Florida.

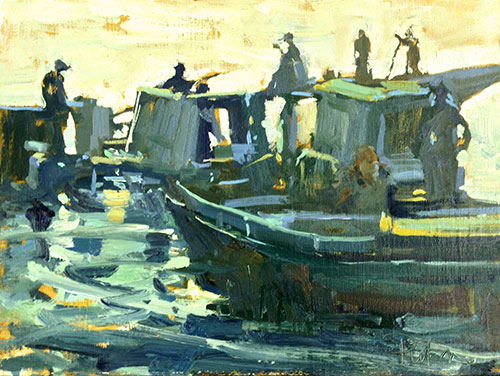

Lead Image: “New Measures,” by Lori Putnam, oil, 8 x 10 in. Private collection

Landscape and wildlife painters today and throughout history have been responsible for bringing awareness of crises through their creative hand. Our unique understanding of what is at stake for future generations is often overwhelming. I recently had the honor as an artist-in-residence to experience firsthand and hear directly from those individuals closest to one such crisis. After meeting with fishermen, congressmen, processing houses, scientists, aquaculturalists, restaurant owners, and tourists, I became aware of just how far the work in oyster restoration being done in the small community of Apalachicola, Florida, extends.

Apalachicola is located on the shore of Apalachicola Bay, an inlet in the Gulf of Mexico, about halfway along a stretch that is sometimes called the Forgotten Coast. A 130-mile length of the northwest coastline, Forgotten Coast covers three counties, and begins in the tiny beach town of Mexico Beach (population 1,100), continues through Port Saint Joe, Eastpoint, and Carrabelle to St. Mark (population 294). Eleven years ago last May, organizers started an annual plein air festival. The original purpose of the event was to invite artists to help the towns document their ever-changing coastline. Changes due to hurricanes, tropical storms, global warming, commercial development north of Florida, and economic downturn are easy to spot from year to year. Little did I know, when I began painting the area some 10 years ago, that I would eventually become part of something so important, and help spread awareness through my paintings.

A vast array of eco-systems provides a variety of painting subjects. I have painted the area on dozens of trips and produced nearly 1,000 sketches. In recent years, I began focusing more on painting the life and marine culture in Apalachicola Bay and Eastpoint, known for the best oysters and shrimp you will ever eat. Everyone from the New York Times to Field & Stream agrees. I enjoyed eating them too. But due to recent environmental and economic strains that have dramatically impacted oyster reproduction, I became more interested in documenting the crises and the plight of Apalachicola Bay than partaking of its fruit. Many of the industry’s structures no longer stand, boats have literally sunk before my eyes as I was painting them, and men and women can no longer work the depleted oyster beds.

One such documentation shows the early morning re-shelling process in Apalachicola Bay. Before sunrise, and as far as the eye could see, boats lined up to take on one front-loader bucket of used shells. Each load was then dumped in a specified location in order to help with the oyster bed restoration. Placing the used shells helps establish a more nutritional and stable environment for cultch (baby oysters) to grow. Oyster beds are fairly fragile. They have survived quite well until recent years, however. Even the area’s hurricanes have typically been just a part of the circle of life. But oysters need nutrient-rich, brackish water, free from sea creatures that now invade and prey on a once stable habitat. It is no longer easy for large quantities of them to grow into the sweet, succulent oysters the bay has been supplying to the nation’s best restaurants (and of course the local joints, too) for generations. Reseeding the beds with oyster cultch by local oystermen each spring for the past four years has been successful, but there is still much work to be done, and alternative measures to examine.

During my weeklong residency, the highlight of my research was the day I spent on an oyster boat with Eugene and Delene Millender-King. According to Eugene, he and his wife once filled five or six 60-pound bags of oysters an hour. Today they are lucky if the get two to four in an entire day. Delene sits on the side of the boat, measuring each oyster one by one as Eugene works with the heavy, scissors-like tools. She is covered in mud and salt with gloves soaked through, using one tool to measure and another to break away cultch and toss them back into the water.

Oysters measuring less than three inches are likely male. Those are not to be harvested. Once oysters reach a certain size, they become female and are considered fair catch. Delene has her measuring tool set to slightly larger than three inches. “Occasionally,” she says, “the newest growth ring will be fragile and break once the oyster is thrown in the bag. I don’t want to take a chance on that so I make sure the oysters are a bit oversized to begin with.” I sat on the bow of the boat, rocking and sloshing and trying to paint. The couple and I bonded in a way that is hard to explain. Something I will never forget: listening, laughing, crying, and sharing oysters on a small, hand-built boat in the bay. Eugene held on to the back of my raincoat while I attempted to harvest a few oysters myself.

Believed to be among the most damaging reasons for environmental change here is the expanding growth in cities north of the area. Fresh water that once flowed naturally into Florida’s pristine bays is now being captured and diverted for residential and commercial use. The lack of freshwater flows from the Apalachicola, Chattahoochee, and Flint (ACF) River Basin has upset the salinity balance. Either there is too much salt, allowing sea creatures and habitat to destroy the beds, or the water is manually released in a way that does not allow for it to flow naturally and slowly, gathering much-needed nutrients along its way. Water then floods the bay, shocking the oysters with fresh water, which reduces the balance needed to maintain healthy oyster bars. The Tri-State Water Wars (Georgia, Alabama, and Florida) have a 20-year history, and in 2013 Florida filed action against Georgia in the Supreme Court.

Years of drought conditions along with climate change are also having an effect on the bay’s salinity levels. Scientists’ predictions for increased temperatures and water levels in the future will continue to impact the industry and those who work in it. Coupled with illegal catch (harvesting undersized oysters), fewer and fewer adult oysters are available. While most longtime oystermen understand the importance of allowing oysters to reach the required three-inch size, there are many newer to this life whose desperate need to feed their families has caused them to turn a blind eye toward the future.

Following the closure of such industries as the St. Joe Paper Company and Arizona Chemical and decreased jobs in construction, the slowed economy meant more people began looking for ways to feed their families. Many turned to the fishing industry. Oystering is generational. Most of the oystermen and -women’s parents and grandparents were also fishermen. But many younger harvesters do not have the same respect for the bays that their ancestors have, resulting in illegal and over-harvesting. New inspections are now required. Following the long day on the boat with Eugene and Delene, we waited in line at the new inspection stations. Every single oyster was checked again for size. The bags are then tagged with an inspection tag. If undersized oysters are found, or untagged bags are caught being sold, there are hefty fines, around $500 for one illegal oyster.

Officers and the youth Conservation Corp of the Forgotten Coast perform the inspections. A comprehensive youth development program for young adults, the CCFC provides participants with job training, academic programming, leadership skills, and additional support through a strategy of service that conserves, protects, and improves the environment, as well as community resilience. This initiative hopes to accomplish an array of specific habitat restoration projects throughout the region, such as invasive-species removal, living-shoreline installation, oyster-reef restoration, water-quality monitoring, and pine-savanna restoration.

Processing facilities in the area, such as 13-Mile Seafood (named for its location 13 miles along the coastline from Apalachicola), were once bustling with workers washing, bagging, and preparing oysters for transport to restaurants and markets. Over 60 percent of the oysters consumed throughout the Southeast (and points beyond) were once trucked from this region. According to Tommy Ward, who is a fourth-generation owner of this company, prior to 2012 they handled more than 250 60-pound bags a day. Now they average just 25.

Ward is one person interested in trying new aquaculture methods for growing oysters. Aquaculture or aquafarming will aid in oyster sustainability — but it spurs a huge debate: It is great for some but not so great for others. There will be even fewer jobs for fishermen who have such a passion for what they know. The large metal cages in which oysters will grow, manipulation of the natural cycle of the oyster, and interference with waterways could have negative long-term effects. Similar to lobster, tuna, tilapia, and salmon farming, there are new regulations and scientific findings pouring in almost daily. Ward, however, is hopeful for the first time since drastically cutting his labor force a few years ago. He sees the number of jobs this will create, rather than destroy.

Proposals and solutions are a constant topic. From visitors to restaurant owners, from fishermen to scientists, from engineers to congressmen, many people are working to assist in recovering a healthy balance for this most significant resource. Each individual with whom I spoke had a slightly different take on the issue. Some were optimistic, some not so much. The one thing all agreed on is that this is the worst it has ever been, and it is not an easy fix.

Joe Taylor (executive director of the CCFC), scientists, government officials, fishermen, and I led a roundtable discussion that was open to the public. I shared the stories behind the sketches I had made during the week. Tourists from Maine talked about similar issues with the lobster fishing in their area. This discussion lead to future plans for potential partnering with other fishing towns as a means to strengthen voices and seek dependable plans for the future. Without fail, everyone I spoke with during my residency thanked me for what I was doing as an artist to help them see the problem in a memorable way.

Following the residency, I returned to Tennessee to work on studio pieces using the sketches I made on location. I heard Eugene and Delene’s voices and replayed their stories in my mind of good days and bad, of loss and of blessing. I later returned to Eastpoint to present my findings through work produced over the years, during the residency, and in the studio. It was difficult to present the devastating facts with such a diverse audience, including several fishermen who had lost so much. You could feel tension in the air during the lecture and the discussion that followed my presentation. Above all, however, was the sense of community and togetherness. The paintings in the exhibit sparked new discussions and ideas.