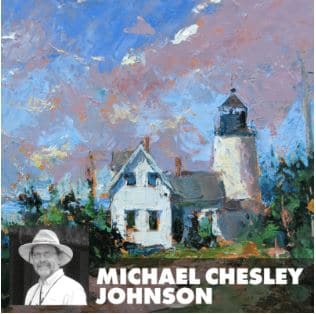

Plein air painter Michael Chesley Johnson explains his “best guess” process for painting landscapes, and how it inspires a variety of styles that span the centuries. Learn from Michael in person at the 2020 Plein Air Convention & Expo (PACE) in Westminster, Colorado, May 2–6!

Making My Best Guess When Painting Landscapes

BY MICHAEL CHESLEY JOHNSON

Like some painters, I have a studio gallery. I’m always amused when visitors enter, look around a few moments, and then ask, “How many painters do you represent?” My answer: “Just me, but I have several painting personalities.”

Unlike some painters, I don’t attempt to create a painting in any definite style. Instead, I like to respond to the landscape before me and to make my best effort in recording my response—however that works out. The result is a catalogue raisonné of styles that spans the centuries, jumping here and there across the globe. Come to my studio gallery, and you may find paintings that resemble Hudson River School, French Realism, French Impressionism, California Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Expressionism, Realism/Color Field . . . well, the list goes on.

As an avid student of painting, often what ends up in the finished work is sometimes the result of trying new materials or techniques.

However, one common thread weaves through all my plein air paintings. It’s a stage in the process that I call the “best guess” stage. Let me take you through the steps in how I make a painting outdoors, and I’ll explain the “best guess.”

First, I look for my subject. I require something that evokes a strong, positive feeling. It could be something about the light and color, about the play of masses or, in a broader scope, about the spirit of the overall landscape and a story it tells. This process can sometimes take days in a landscape that’s new to me, or just moments when I walk through a landscape with which I’m intimately familiar.

Once I’ve found my subject, I take the time and trouble to make a few design sketches. Once upon a time, I used to skip this step—quite often, a design will come to mind that I feel intuitively is “right”—but I realized that besides design, a sketch helps work out values. It gets the eye, hand, and brain working together so they can understand the values better. It’s also an opportunity to adjust value relationships. Sometimes, I come up with a more effective set of value relationships than does Nature.

After settling on a design and coming to understand the values, I lightly sketch it on my canvas. (Or paper, if I happen to be working in pastel rather than oil; I work fluently in both, as well as in gouache and cold wax.) At this point, the painting is all about big, simple outlines.

Now for the “best guess” and the block-in part of painting landscapes. Some painters will take the time to mix an exact match to what they see in their subject, or try to do so. (Pastel painters often fret that they don’t have the right color in their box.) Depending on the experience level of the painter, this can be quick—or not. Often, it’s frustrating. A dab of color goes down on the canvas and looks right; but then you put a dab down for a different color, and that first one looks all wrong. One way around this, of course, is to pre-mix all your colors on your palette and compare them side-by-side before committing them to canvas.

Meanwhile, the shadows are moving, and the tide is going out, changing the contour of the waterline . . .

I prefer to make my best guess rather than to agonize over and waste time in mixing or selecting the exact color. Instead, I mix color rapidly, taking into consideration value and color temperature first, and hue and intensity last. If the color is dark enough and cool enough, or light enough and warm enough, that’s all that really matters. And even if I am “off” on these two properties, then so be it. I keep going.

However the color goes down when I’m painting landscapes, I tell myself that I can adjust it quite easily. Having engaged in pottery briefly in my youth, I like to compare this process to shaping a lump of clay. You start off with a lump, kick the wheel, embrace the clay with your hands, stick a couple of fingers in the top, and soon you have something that looks like the beginning of a bowl. From there, you can build it up or tear it down and just keep massaging it until you get what you want.

I find this step incredibly relaxing and enjoyable. Massaging color on the canvas becomes a form of meditation.

From here, I continue working until I achieve whatever goal I set for myself with this particular painting.

By the way, it’s important in the “best guess” step to keep the paint thin but not thinned, or at least not so much. The drier the paint is, the better it will stick to the surface and not churn up when the adjustment layers are applied. (With pastel, I like to fix the block-in with a spray of alcohol.) If possible, I use paint right out of the tube, thinning only if necessary with the tiniest amount of Gamsol. I also have found that a somewhat absorbent ground helps. (I make my own panels from hardboard to which one layer of Gamblin’s PVA Size has been applied, followed by two layers of Dick Blick Master Gesso. If this is too absorbent, I add a layer of Golden’s Acrylic Matte Medium.)

As one of the artists invited to demonstrate at PACE 2020, I’m looking forward to showing you in person how this technique works for painting landscapes.

About the Artist

Michael Chesley Johnson, a Signature Member of both the American Impressionist Society and the Pastel Society of America, splits his year between studios in New Mexico and the Canadian Maritimes. Also a teacher, he teaches frequently throughout the year in many locations. He is on the faculty of PACE this year in Denver. For more, visit www.MChesleyJohnson.com.

Upcoming travel and art events with Streamline Publishing:

> Click here to subscribe to the free newsletter, Plein Air Today

> And click here to subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue!