Canadian artist Claude Millette is not alone in his love for painting water. But its particular draw for him rests on a paradox.

“Rushing Water,” by Claude Millette, oil, 42 x 42 in. Studio

He’s painting a static, 2-D image, but what he likes most about his subject is its movement. “I’ve been mesmerized by water imagery since I was a teenager,” says Millette. “I used to go jogging by the river, and I’d go down by the falls and meditate by it. I still tend to go to rivers and walk along them. I am a big walker, and I spend a lot of time watching water reflections.”

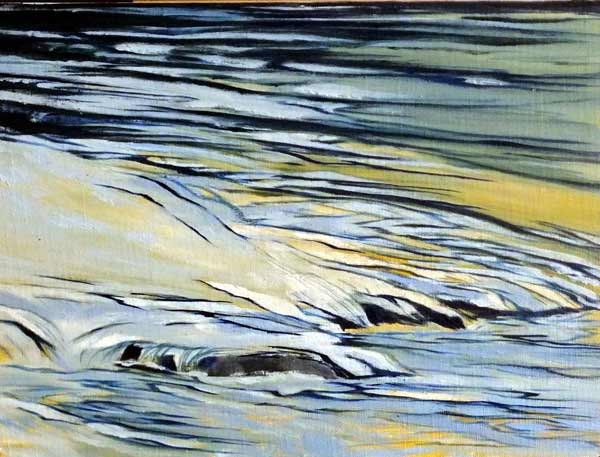

“Rushing Water Humber III,” by Claude Millette, oil, 12 x 16 in.

Millette lives by a lake, but even there, where waters are more still, his eye goes to the small waves at the shoreline. His favorite water feature is rapids. “There’s an issue of power and color in rapids, in that moving, frothing water. It’s a sign of the power in nature, in the world that will still be here long after we’re gone.”

“Petites Chutes,” by Claude Millette, oil, 48 x 48 in. Studio

It’s the movement he likes, but it’s the structure of the riverbed that gives the water its movement. The shape of the river’s bottom creates the still areas and the rapids. Millette zeroes in on the dark depths and the surface highlights, finding the value contrast therein, and looking for an interesting hue within it all.

“Calm Amidst the Storm,” by Claude Millette, pastel on board, 18 x 24 in.

“There’s usually some kind of rock structure, and I paint the movement of the water around that,” he says. “I sketch in the position of everything, then I start playing with color. I do the large masses. But really, it’s an interactive thing — I don’t know what it’s going to look like. I tend to show the interplay and contrast between dark and light and that ‘something’ that makes the movement.”

“Humber River Lambton Bridge,” by Claude Millette, oil on linen board, 16 x 20 in.

Millette, a family therapist, has long carried a sketchbook with him. He is well acquainted with the grayscale, and the use of value. But although he considers himself a newcomer to color, it’s usually a hue that catches his eye and draws him to a scene.

“Yes, usually one color attracts me more than the others,” says Millette. “If there’s a gold ochre, it’s probably going to be that. I’m less attracted to blue.”

“Toews Falls Rushing Water,” by Claude Millette, oil on linen board, 16 x 20 in.

Millette made the switch from drawing to painting due to a tragic event: His wife passed away. As he struggled through his mourning, he found himself playing around with his wife’s pastels. “I was never really able to do color,” he says. “My wife painted in watercolor and I would watch her. Color was her main thing. After she died, there were pastels around and I learned to play with them, essentially because they were an easy medium. I could draw with them in the house and just get up and leave them and go to work. I got some books and learned some theory and started experimenting with putting color together. It’s not a natural thing; color is something I struggle with. I end up with large contrasts with color and value and strong colors.”

“Humber River Rushing Water II,” by Claude Millette, oil on board, 16 x 20 in.

The pastels, and the artwork in general, helped Millette through a difficult time. When his clients saw his work in his office, they urged him to have an exhibition. Millette’s first show was titled “The Color of My Darkness,” in reference to the genesis of this new mode of expression for him. “It was not an expression of my depression,” he says. “The paintings were a way of being mindful of the outside world. In that first year, I started out just living one hour at a time. Then four hours, then a full day, then a full week. I was not expressing the emotion inside. Plein air painting allowed me to not feel, but rather be present to what I saw. While I never intended to pursue this too far, the reality is I have been caught in the web of this creative experience, and now I need to paint daily and I can’t wait to get back to my easel.”

Millette is now in his second year of painting outdoors. He finds himself “adopting” rivers, concentrating on one of them for a while, depicting it in various conditions. His goal is to learn more about using transparent colors to depict the scenes. “I want to get the greens and browns of the river to shine through each other,” he says.