Plein Air Painting and Studio Enhancements

Whoops, did I write that? There must be a mistake – you’re not allowed to work on plein air paintings in the studio, right? I mean that would be a sin, right? ☺

Well…hold on there Jasper, who told you that you can’t do that?

The truth is, somebody did say that somewhere, but some other somebody at one time or another said it’s ok… so which is it?

Now that we’ve established that it’s an opinion, I’m going to give you mine, with the emphasis on the word opinion, because, after all, that’s all we’re dealing with when it comes to this question; so here goes…

Question: When is it “not okay” to work on a plein air piece in the studio? Answer: That time would be when you are involved in a plein air competition and the rules say not to do that, period! Wow, that was easy! Now, when is it ok to enhance a plein air painting in the studio? And the answer is…(envelope please)…all those other times! Or in other words, aside from the first example, whenever you want to, because you’re the artist and you get to decide!

So when would you do that?

Here’s how I look at it: Which is more important, being a purest or coming away with a really good painting? The late Helen Van Wyk used to have a saying that went something like this – “No one cares about how much you suffered over a painting, they only care about how it looks in the end!” I have to agree, and no one should care as much as the artist about how their painting looks in the end, so stop fretting, and let’s get to the business of creating quality art.

(Before I proceed, lest anyone thinks that I’m trashing plein air painting, believe me, I’m not. Plein air painting is the lifeblood of any landscape painter’s work. Without years of dedicated experience painting outdoors, I dare say, that a true landscape painter would be reduced to a mere photocopier at best. It’s out there in nature that the real heart and soul of the visual world is revealed to the artist. It’s there, where they can see into the shadows and perceive light and atmosphere in a way that no photographic reference could ever match! Yes, plein air is essential for artists who truly want to imbue our work with life, and a true feel for the authentic experience of painting on location!)

Having said that, there are plusses and minuses to everything, and there are certain tradeoffs and benefits when it comes to choosing to work one way over another. For instance, out there, we are always limited on time. As shadows change, the need to work quickly can inhibit our perceptions as we concentrate on getting the job done before our subject changes too much. As we concentrate intently on one area of the painting, other areas may take a back seat until we have more time away from the subject to contemplate needed adjustments. Those adjustments might be as simple as strengthening some darks or adding some highlights, the addition of a subtle color shift, or perhaps some color gradations. Maybe the painting needs a bit of simplification or some more surface quality. The list goes on and on, but you get the idea.

Many times we come back from a day’s painting on location and bam, that painting just sings and nothing needs to be done! Those are satisfying times to be sure, but what about those times when a little more finesse would go a long way in making your painting exceptional? What are you going do, not fix it?

I know what I’m going to do, I’m going to make the work better and also sharpen my artistic senses even further by exploring design possibilities that I didn’t have time to consider out there. After all, don’t my collectors deserve that? Don’t I, the artist, deserve that as well? The answer is yes! If you can spend a little time making a painting better, wouldn’t it make more sense to do that? After all, it’s your artistic sensibilities that really matter and also your reputation as an artist. So make that painting better… what would be the downside?

By the way, there’s more than one way to do this; in the case of a competition with rules, you could return to the same spot a day or two later and finish up outdoors. On other occasions, a studio experience might be just the thing to work out further enhancements.

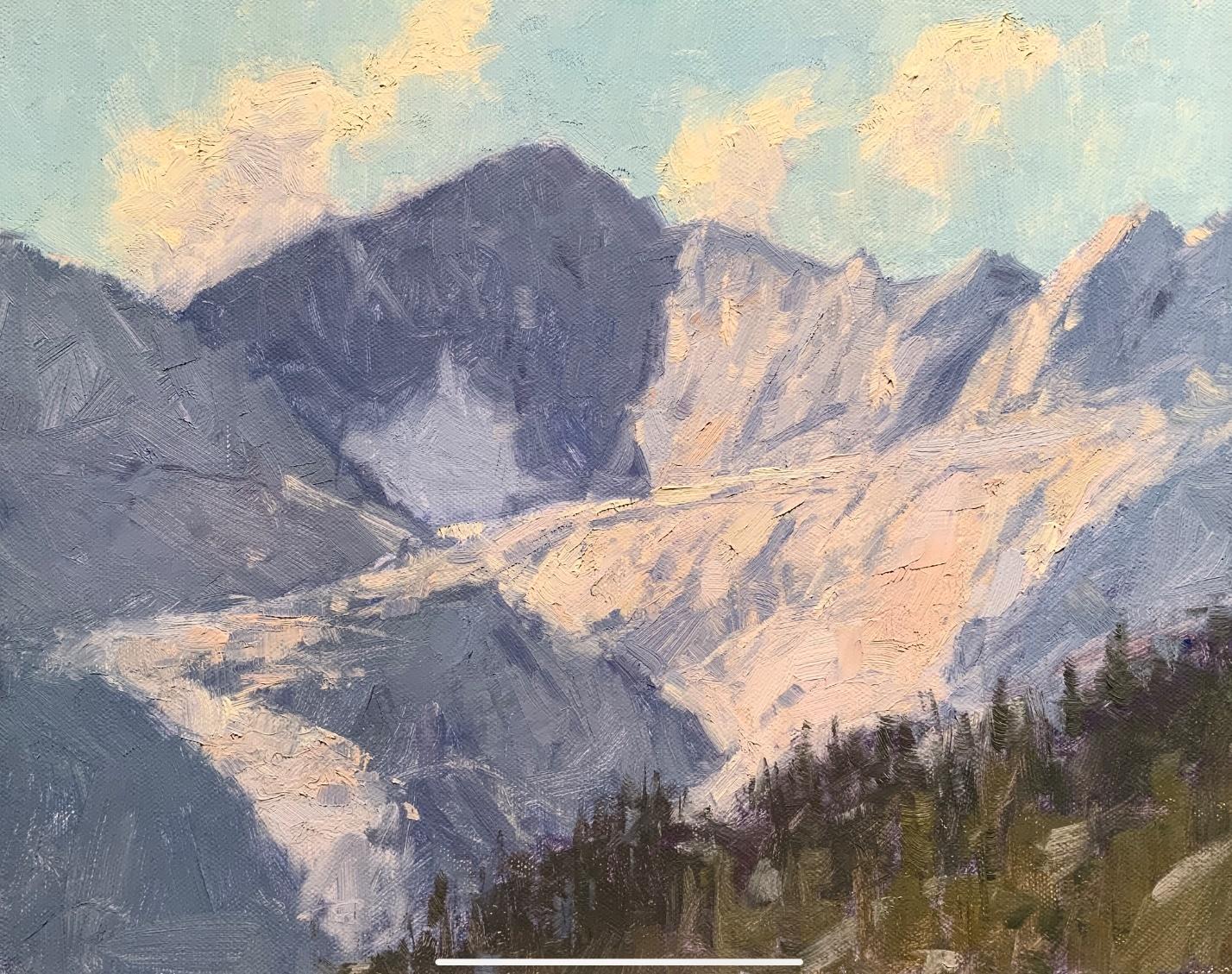

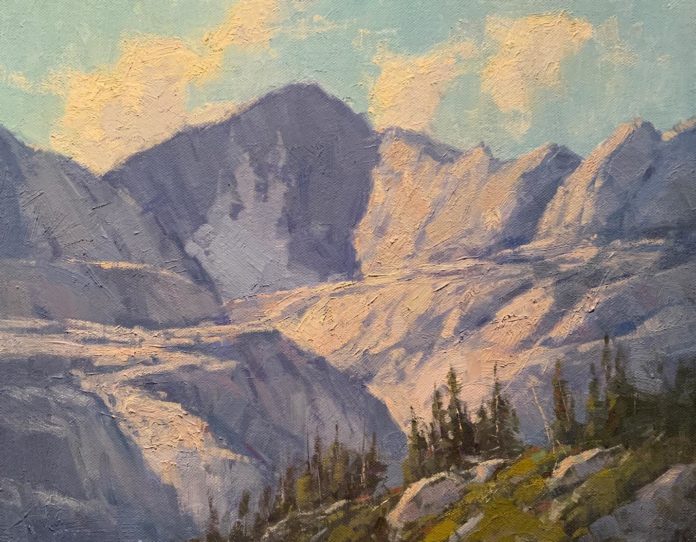

Take a look below as I walk you through a study that served its intended purpose as a class demo for my students, but needed more refinements in order to make it a piece that I could be proud of and take to a gallery.

By studying this painting’s original faults, I have improved the work itself and my own understanding of design, which will go a long way to making me a better designer when I’m out on location.

Until next time,

John

Visit EricRhoads.com to find out all the amazing opportunities for artists through Streamline Publishing, including:

– Online art conferences such as Plein Air Live

– New video workshops for artists

– Incredible art retreats

– Educational and fun art conventions, and much more.

> Subscribe to Plein Air Today, a free newsletter for artists

> Subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue

Regarding “Without years of dedicated experience painting outdoors … a true landscape painter would be reduced to a mere photocopier at best,” landscape painting precedes both photography and the practice of painting outdoors. Pieter Bruegel the elder painted realistic landscape without photography and without painting in the weather.

And from the other direction, well after the advent of photography and the practice of plein air painting, Henri Matisse painted his fauvist landscapes outdoors sur le motif, though he took great color liberties with his subject. Well, for that matter, Van Gogh painted his amazingly unique landscapes from life too.

There are no rules — except for contests.

On article “to finish a plein air in the studio”…THERE was no reply box for that article. My opinion, having painted ‘en plein air” since 1987…the answer is VERY SIMPLE:

A true “PLEIN AIR PAINTING” should not have more than perhaps 15 or 20 minutes of “touch up” in the studio, (if any at all) to be labeled a “plein air paintings”. Many artists do “sketches on location” then spend HOURS in the studio and call that “a plein air”. SORRY, THAT is a studio painting!! PERIOD! “Plein air” has become a real “catch word” these days…and those who call their studio piece plein air, are mere marketers…they are not “plein air painters”. Call it what it is: They are LANDSCAPE PAINTINGS. Period! http://www.bettybillups.com

Hi Betty,

It’s always nice when a well respected professional like yourself weighs in on these discussions. Point well taken. Yes, if we get into the topic of labeling these paintings it’s best to do it accurately. Some of these efforts could very well morph into studio art which isn’t always an improvement either!

What if, at a Plein air competition that says no painting after the fact, another artist spends hours “finessing” their work? Does one report this behavior? Suggest to the artist that what they are doing isn’t kosher? Stuff it?

What makes the other artist’s behavior wrong is not the finessing of the picture, but the decision to enter it into the competition when doing so clearly violates rules that the artist agreed to honor. In that sense it’s no different than any other kind of minor fraud. But finessing the painting — when it is genuinely an artistic decision is marvelous, I think. When you have ideas about how to make the painting better, personally, I think you should use them. The painting ought to count more. If the painting is “that good” (to the artist) it should matter more than the contest does. And then understand the contest as having been the occasion that led to the realization of the painting. In that case, the artist should perfect his picture, but not include that picture in the competition only because it no longer satisfies the contest requirements. Let that picture be art for its own sake. At some juncture art has to stand alone, separate from all its references, and the work of art becomes a little world unto itself.

Good thought, thanks for sharing with us.

Hi Gail,

I would just say do your best work and obey competition rules and be happy with that. We can’t control what others may or may not do, and personally I don’t want to be the Plein air police. I’d rather savor the experience outdoors and drink in the sunshine. Just my opinion.😎