Do you feel pressured to paint faster when en plein air? If you’re tempted to practice the “smash and grab” technique, you might want to think twice. Here’s why.

The Pace Race

BY KIM CARLTON

Like any vital, living thing, the art world is ever evolving. In the distant past, paintings were accomplished in the studio by painstaking application of layers of paint over a period of sometimes years.

In the not-so-distant past, the trend toward alla prima painting increased the expectation of completing a piece in a much shorter time span. In the present day, time-lapse videography has made it possible to witness a 3-hour painting demonstration in eight or ten minutes!

Now, there’s a wicked thing in my head that tells me I’m incompetent if I can’t paint a decent demo in eight or ten minutes. Not literally but, well, almost literally. The truth is, I’m a slow painter. I want to be a fast painter and this has steadily stolen my focus away from the simple joy of painting.

This year, I am learning that I am not alone; there are a bunch of us trying to get faster. It’s a painter’s version of anorexia: you see the magazine cover of the perfect quick-draw painting and look at yourself to see if you’re good enough. You’re not good enough in your eyes so you start starving yourself and exercising and self-destructing, when all along you really were good enough; you were just different! Maybe you need someone to tell you that. Maybe I do, too.

Plein Air Goals

At the end of last year, I decided that I wasn’t fast enough to be good enough to call myself a plein air painter. I set specific goals, and my Number One Goal was to learn to be a really fast landscape painter. My training until then was exclusively studio and mostly portrait-oriented, and while I’d been painting outdoors for more than a decade (and frankly loving it with an unadulterated love), I’d never actually been taught how to paint en plein air.

My plein air works were, in the words of Robert Genn, “unabashed two-steppers.” I would paint as much as I could on site and then finish the rest later, using my mixes, my start, and my reference photos. I hadn’t entered any plein air events because of that, and I have felt more and more ashamed about it.

Well, that was all about to change because I signed up for two workshops: one with Ray Roberts and the other with Jill Carver.

Both of these great artists and great teachers asked their students what they hoped to gain from the respective workshops and the answers were pretty much the same: we all wanted to learn to think and paint faster in the field; to come to a place and be able to compose a finished painting in our head while we were setting up, mentally Photoshop trees and rocks and rivers in and out and all around a canvas, and finally to capture the essence of it before the light changed, be able then to slap a frame on it and win a gold medal. That’s what we all hoped to learn.

Here’s what we all did learn: sometimes what you think you need to learn is different from what you actually need to learn. The gentle admonition from them was, it’s not about speed: that’s asking the wrong question.

Jill suggested that there would never be an entry in an art book saying, “Painted between 2:00 and 3:45 p.m., whilst competing against so-and-so.” No, the painting must forever speak for itself and if you can’t paint it well going super fast, slow down.

Neither of these painters comes to a landscape with an expectation of coming away with some kind of slap-dash masterpiece.

Roberts’ approach was to consider plein air work as fact-finding and idea-catching, making numerous small sketches with an eye toward a studio piece.

Carver’s strategy was to make it less of a hunting expedition (her words) in which you “bag a prize,” and more of a private conversation with a friend. Her approach was very slow and polite; sketching ideas in a book with a sharpie and making notes before her kit was ever unpacked for painting. When she does get her gear out, she often divides up the canvas into two or four sections upon which to paint her response to the landscape. I’ll tell you how this affected me: I felt liberated from my own expectations and free to be myself out there.

When I watch great painters paint, they do not ever seem to be in a hurry. Even if they accomplish a painting in a short time span, they are very deliberate in their application. I felt all warm and tingly when I learned that my hero, John Singer Sargent, might paint and scrape a head 16 times, so as to ultimately leave a fresh mark that seemed quick and effortless.

But even before that, he’d done dozens of sketches. Seeing the plein air studies of another hero, Joaquín Sorolla, was exciting because they were all so tiny and jotty, like the shorthand notes of a writer! When I shared with my husband my new goal to be a faster painter, he said, “You don’t do anything fast! Why would you want to do the thing you love the most fast?” None of these things will sink very far into a hard head.

When Jill Carver paints a place, she has first loved it. Her painting is a poem about it. She has already sketched different versions of it and maybe paints several studies before she approaches the Painting Proper. When she set up for one demo, she situated her canvas so that her back was toward the subject. By doing this, she could only paint whatever she remembered once she was facing the canvas. This is an old Robert Henri trick. It requires a bit of your soul.

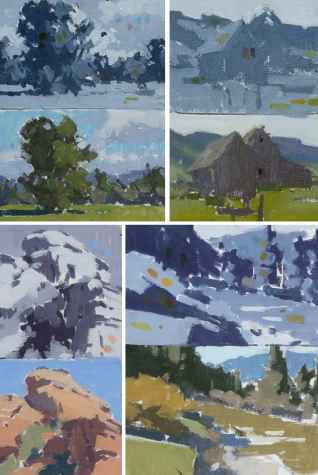

Here are some studies done by Jill, exploring the number of values needed to convey a scene, preferring to keep it between three and five. This is one of the ways she helps her students to deconstruct and tune into the scene. Note the way she matches the colors to the values.

While we were working outside, her repeated, disarmingly funny, admonition was, “Paint what you see and keep it simple: after all, this is not rocket surgery.” She encouraged her students to relax and let the scene choose us, let it reveal itself to us; that requires calm and quietude. It is much more courteous and respectful than the smash-and-grab technique that I thought I wanted to learn.

Ray Roberts was working with rapidly changing light because, as luck would have it, we had rare weather blowing through the desert while we were out there, including riotous thunder storms!

It was exhilarating to watch him work; he engaged the constantly changing light by constantly changing canvases! I know I would have decided to stay in the studio if the weather were unpredictable like that, but he taught us to move with the weather, to let it speak to us and take dictation so we could report our experience later.

Our steno pad was the canvas, 8x10s quartered, so that we could make four 4×5 inch paintings of the changing light. If he ran out of space, he tossed one canvas panel to the ground and picked up another, never chasing the light in one piece, but letting every change have its own space to speak. And again, he wasn’t slapping on the paint at 90 miles an hour; he was brief and deliberate, making exact notes that would bring a flood of memories back in the studio. His experience in the field was respectful and joyous, and that was conveyed in both the sketches and in the studio painting he did from them.

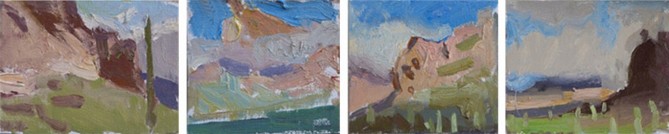

Here are some of the field studies done by Ray, and the studio painting that sprang from them: Notice how pieces of the studies found their way into the final painting, which truly captured the spirit of the experience, even though that single scene only existed in his mind’s eye.

A Marathon or a Sprint?

Having been a runner, I know that there are some people who are good long-distance marathon runners, and others who are good short-distance sprinters; there are very few people who are good at both.

There are master artists who enjoy the quiet, drawn-out pace of a marathon painting, working weeks or months (or years!) on a single piece, but who could not do a one-hour demo in front of an audience to save their own life.

Then there are master artists who absolutely love the adrenaline-fueled fast pace of the quick-draw events and are astonishing in their ability to nail a sketch in one or two hours, but who could not spend any more time than that without going stir-crazy, and would never re-enter a painting that’s been “finished.”

But! Sprinters do run long-distances when they are in training, and distance runners do train by running sprints for the same reason: it makes them better at what they’re good at.

So there are sprinter-painters who start out with a bang and run full-tilt to the tape, and there are marathon-painters, who have a relaxed stride and who pace themselves to endure a long run. But here’s the thing: painting is not a performance art.

Jill’s right: the thing that will outlast us is the body of work we leave here. Focusing on speed, even if I secretly still want to paint fast, is focusing on the wrong thing. Use speed-painting as an exercise, not as a standard of excellence. Paint a lot! Remember, a million miles of canvas is what it takes to make a great painter. And the more a person paints, the better a person learns to say more with less. And, it will happen at some point that it will take less time to do that well.

Ray Roberts and Jill Carver are able to produce masterpieces in the studio that are gleaned from their work in the field. They are also able to produce truly inspired pieces in the field because they are out there working in all weather, day in and day out: they are good because they train and hone their gift.

So now I’m reassessing. Sometimes a person has to readjust their goals in order to be true to their purpose. My real purpose is to be the best artist I can be, and maybe I, personally, can’t do that by painting fast.

We who call ourselves artists have chosen to run a road that is not easy, but we love it and that’s why we’re here. Applaud the sprinters, cheer the marathon runners, and enjoy your own journey. Press in happily and hard to the thing that makes your heart skip and sing when you paint.

There are a lot of things going on out there but we really don’t have to do them all; we’re not failures if we don’t do them all. We need to just do our best thing in the very best way we can. Getting to do what you love is such a rare thing. We shouldn’t ruin it by wishing we could do something else. I think the thing I was starting to lose in my quest for quickness was the experience of just enjoying spending that time doing what I love to do!

That old adage, “haste makes waste,” is an old adage for a good reason: it’s true! Haste could waste the thing that made you start on this road to begin with: the joy of painting.

So I’m adjusting my sights for the second half of this year: the point is the product, not the pace; this is not a race! I’m going to write a card to stick to my Soltek: “Haste Makes Waste ~ Embrace Your Pace.” Even if I still feel the need for speed!

Learn more about Kim at: kimcarlton.com

Check out the following amazing opportunities for learning with Streamline Publishing:

- April 15-17, 2021: 2nd Annual Plein Air Live virtual conference

Book Your Early-Bird Discount before 11:59pm PT February 28 and save p to $600 off the full rate - January 27-29, 2022: 2nd Annual Watercolor Live virtual conference

Book Your Early Bird Discount before 11:59pm PT on August 31 and Save Up to $600 Off the Full Rate

> Click here to subscribe to the free newsletter, Plein Air Today

> And click here to subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue!

So grateful for Kim’s article. I am a slow painter. Kim gave me permission with no shame to paint the way I do but she also gave me a challenge; hone my craft.

Thank you for your response~ the joy is back <3

Thank you, Kim for this great article! I appreciate the challenge of trying to change and adjust to what one “thinks” is the better way to do something. I’m grateful to continue to learn and grow from others like you willing to share your personal efforts.

De! That was one of the most important take-aways from these workshops: Sharing the hard-won lessons elevates everyone! Thanks a lot for your encouragement.

Thank you for this article and sharing your experiences and observations.

I have likewise been struggling mightily with how long it takes me to make a painting that I want to put “out there” and how that relates to my competency as an artist. The advice and counsel here has gratifyingly seconded my decision to put final product over pace of production. I want each work to be the best I can make at the stage of my career that I am in. Then, let it go, and make the next one– hopefully a little better yet.

Really great wisdom, Sherrie! I wish I could get back all the awful quick-works I posted when I first started blogging. Yeah, they were fast, but they were genuine junk. Looking at Sorolla’s plein air work, like I said, flooded my soul with relief. I love his finished pieces, which were based on his plein air work. But his field work was tiny and filled only with color notes. I’m still not good at that but at least I’m having fun again. My studio work has relaxed also. Your last two sentences are words to paint by~ thanks.

Great Article and so true in my case. Many Thanks