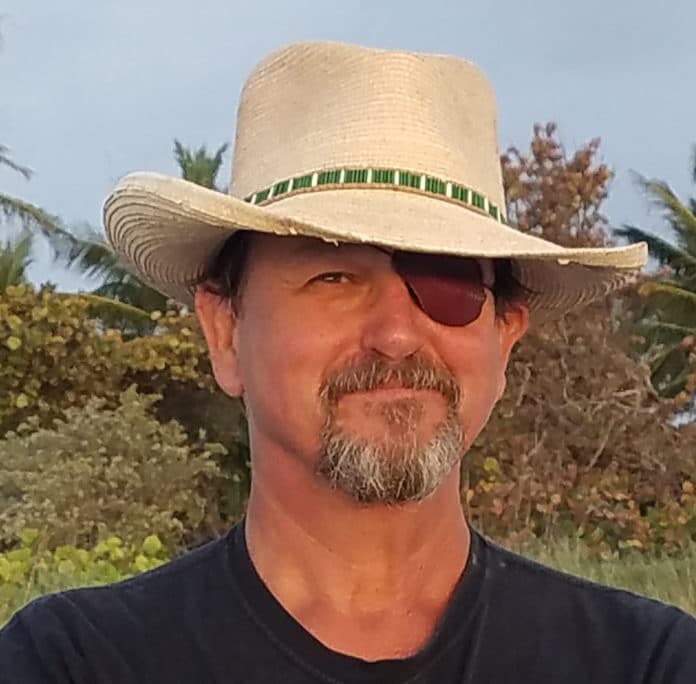

Welcome to the PleinAir Podcast with Eric Rhoads. In this episode Eric interviews Lon Brauer on entering – and winning – plein air competitions, and much more.

Listen as Lon Brauer shares the following:

• The surprising utensil that’s his favorite when it comes to creating texture

• Painting what sells versus painting what’s true to oneself

• Tips for painting on a large canvas, and more

Bonus! Eric Rhoads, author of Make More Money Selling Your Art, shares advice on how to know which publications in which to advertise your art, and insights on paying percentages to art galleries in this Art Marketing Minute Podcast.

Listen to the PleinAir Podcast with Eric Rhoads and Lon Brauer here:

Related Links:

– Lon Brauer online: https://www.lonbrauer.com/

– Eric Rhoads on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/ericrhoads/

– Eric Rhoads on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/eric.rhoads

– Sunday Coffee: https://coffeewitheric.com/

– Plein Air Convention & Expo: https://pleinairconvention.com/

– Plein Air Salon: https://pleinairsalon.com/

– Publisher’s Invitational: https://publishersinvitational.com/

– Value Specs for Artists: https://streamlineartvideo.com/products/paint-by-note-red-glasses

– Paint by Note: https://paintbynote.com/

– The Great Outdoor Painting Challenge TV Show: https://thegreatoutdoorpaintingchallenge.com/casting-call

– Figurative Art Convention & Expo: https://figurativeartconvention.com/

FULL TRANSCRIPT of this PleinAir Podcast

DISCLAIMER: The following is the output of a transcription from an audio recording of the PleinAir Podcast. Although the transcription is mostly correct, in some cases it is slightly inaccurate due to the recording and/or software transcription.

Eric Rhoads 0:00

This is episode number 177. Today we’re featuring artist Lon Brauer, the artist who’s been winning all the big awards lately.

Announcer 0:27

This is the plein air podcast with Eric Rhoads, publisher and founder of plein air magazine. In the Plein Air podcast, we cover the world of outdoor painting called plein air. The French coined the term which means open air or outdoors. The French pronounce it plenn air. Others say plein air. No matter how you say it. There is a huge movement of artists around the world who are going outdoors to paint and this show is about that movement. Now here’s your host, author, publisher and painter, Eric Rhoads.

Eric Rhoads 1:05

Thank you Jim Kipping and welcome everybody to the plein air podcast. I hope you’re doing well. I know these are crazy times. And it’s important to keep your sanity. One of the best ways to do that is to keep focusing on your growth as a painter learning and growing learning new things. I have been live each day trying to help you do that at 12 noon, Eastern. And we’re trying to keep things upbeat, keep your head in the right place, and I’m giving marketing advice prizes, and offering two video instruction segments a day from some of the over 400 artists that we represent. To find me live. Go to Eric Rhoads. That’s r h o a d s and follow me. Don’t do a friend request on Facebook because I have limits on how many I can do and they don’t let me have anymore unfortunately, otherwise I would but you can still follow me on Facebook or you can follow me on Instagram at Eric Rhoads and I’m on YouTube at streamline art. video just go to YouTube search streamline art video and hit the follow or subscribe button. Alright, just go there and search streamline art video and subscribe. If you have been watching those you would have learned that I announced a big dream that I’ve been working on bringing all the plein air painters in the world together for a global virtual event. That’s right, it’s going to be amazing. And it’s going to be something you’re going to want to be a part of, and to be sign up to be notified. Or to learn more, go to Plein air live.com that’s Plein air live. It’s coming up on July 15. And there’s a four days of virtual summit it’s going to be so cool. Plus, there’s a fifth optional day a first day actually, for beginners, people who are brand new to planner who want to know the ropes, about equipment about various forms of paint about all the things they need to know. And that will save you a couple of years, though my Adirondack 10 year anniversary event is now sold out. There are more things that we offer you to do. We’re moving forward as planned with the Plein air convention August in Santa Fe first time in the summertime. And we have an amazing lineup. And we have a money back guarantee to of course, just in case you are we have to cancel or reschedule due to Coronavirus or the conditions at the moment. So you can visit pleinairconvention.com to learn more about that in the light up is is as good as any lineup we’ve ever had. A reminder that at the end of the month, it’s the last chance to enter to win the plenary salon art competition. There’s a $15,000 Grand Prize, lots of other prizes for the monthly competitions but also for the annual and if you win in any category in the monthly. You’re not all if you get entered into the national competition for the big prize which we present at the plein air convention and so there’s not too many more of those. I think there’s one more probably the month of July. And then we’re going to be doing the judging and have it for the plein air convention for onstage. So enter at plein air salon.com. And we don’t have to have fresh paintings we don’t. We don’t believe that that’s the way our competition should go. You can have any painting you’ve ever done. And of course, every judge it’s really interesting because some judges, like certain types of paintings and others don’t. And so you can see somebody enter something one time and not get judged in and then they enter it again another judge goes Wow, I like this painter. The other thing that’s interesting, we use a lot of gallery people and a lot of them are discovering painters and inviting them into their gallery so that’s pretty cool too. No guarantees on that of course. Coming up after the interview, I’m going to be answering some art marketing questions in the art marketing minute but first let’s get right to our interview with the amazing Lon Brauer. Welcome to the plein air podcast.

Lon Brauer 4:56

Eric, thanks for having me on. This is this is quite an honor. I’ve listed a bunch of the podcasts in the past and they’re always interesting. So hopefully this will be busy as well.

Eric Rhoads 5:07

Well, if it’s not interesting, nobody will listen.

Lon Brauer 5:09

Yeah, there you go. You can just throw it out. No pressure. Yeah, there you go.

Eric Rhoads 5:17

So on you and I met in the Adirondacks. And, as happens very rarely but happened when you were there. Everybody was clamoring to your work. Everybody was in love with your work. And, and your work stands out, because it’s different than what everybody else tends to be doing. So I want to talk about that today. Amongst other things. I know that you’ve been kind of before Coronavirus, you are rocking it. You’re winning lots of awards, getting invited to a lot of events. So let’s kind of start from the beginning. How did this whole painting thing begin for you?

Lon Brauer 5:56

Well, I go back to the beginning. You know, I started like everybody else as a kid, you know, as drawing and painting and then making things as a kid and and I, you know, but the idea of being an artist, you know, for a career or anything like that was, you know, that was just a pipe dream. My dad was a pharmacist to my mom was a nurse. So, and I’m the oldest of four. So I was going to be I was gonna be a pharmacist. And so my, you know, going through school was all about, you know, math, science and English and you know, those sorts of things. It was, you know, very academic, and, you know, any art classes that were available in grade school in high school, I just really didn’t have time for it didn’t fit in my schedule. But I had an opportunity to, there’s a guy in town I grew up in Illinois and live in a small town and there was a fellow there who worked for International Paper. We had a plant there and he was one of the graphics people. And while he was the graphics, he was old department, but he also did painting on the side and he Lesson so I was able to get hooked up with him when I was about 15 I guess. And, you know, we I, you know, I it was just basic once a week art classes and he we started out with still lifes and working in charcoal and about three, three, within about three weeks we were we were doing portraits because that was his thing. And so I think that’s where I kind of got in the gut, the figurative bug, but again, it wasn’t ever really a time about 15 1515, something like that. So, um, but you know, when it came time to go to college, it’s like what I’m going to do, I went to a few, we, you know, mom and dad took me to several schools, and we we interviewed and they said, you know, yeah, he can be Yeah, he’s got a pretty good portfolio, but he’s gonna, if you if you’re not going to teach, what are you gonna do with it? So this is Midwest and so I end up going to a liberal arts college for a couple years, thinking that I would get a biology degree and things like that. was my next strongest thing and I took a few classes there in painting classes. And I thought, No, this is this is what I need to do. And I that’s what I transfer to wash u or Washington University in St. Louis, and went through their program and so, but I came out as you know, I came out of school as a painter, a figurative painter primarily. And I was the this was this was 1976 to 80. And the the faculty, there were all abstract expressions. You know, the Kooning was still painting and Rauschenberg and all these all these guys and, and they but the program was set up in such a way that yeah, that’s what they did, but they taught a fairly good cornet, a good core program. Drawing was very important. And, in fact, we had one guy that I just adored there he was, he taught figure drawings and, you know, it was very, I wouldn’t call it academic, but it was, you know, the fundamentals were there. And by Anyway, I came out of school and I thought, Okay, what am I going to do with this? So, and I was getting panicky I had a whole summer I didn’t do a whole lot but pour concrete and then a friend of mine who was working at a photography studio called me and said, We need some help. It was a they were doing studio work catalog work and said, We need some help in the darkroom. Are you interested in I said, Oh, yeah. And, boy, I did that I was gonna be a part time gig and I went from working in the darkroom to eventually being an assistant. And then I, you know, within a year, I was a shooter. And I ended up being a 30 year career. So 30 years. Yeah, it wasn’t planned at all. It was just, I just, I’m glad I did. I mean, it was a great, great thing to do. But you know, the whole time I was doing it. I’m thinking to myself, yep, I’m a painter. So So and when when the time I had in 1991, I went and I opened my own studio. And, you know, I had a I had a good Stable of clients. And every time they would bring a project I was shooting widgets, primarily, you know, is like service catalog work. But there were times when I could stretch a little bit. And, you know, as you know, here, I’m working with view cameras, I’m working with film and I’m working with, you know, photographic images, but I’m trying to always to make them painterly. And, and, as was anybody else at that time, this was in the 90s. You know, so we were running, doing all kinds of stuff before Photoshop. So we’re trying to do all kinds of manipulations in the camera to make the image although it’s photographic to make it look as if it has that painterly quality, whatever that is. And, you know, we got into things like Polaroid transfers, you know, where you can take an eight by 10. Polaroid, and transfer it to a piece of paper. So now it feels like a piece of art as opposed to just, you know, select photo image. Yeah, I used to be no Yeah, yeah, you know, so, and I was doing all kinds of and I actually early on I started doing all kinds of manipulations in darkroom where, you know, we’re playing with different development speed, you know, well first you take the film and you’re pushing and pulling, and then you’re scratching the film, and then you’re making prints and you’re, you know, and then you’re distressing the print and then you’re going into the stop, and then you’re going into the fixer. And then maybe you go in the fixer, Nickelback to try to go back to the, to the developer and the flashing stuff, you know, all this kind of stuff. And but, you know, the whole time I’m doing it’s a job and it’s in, it’s in, it’s in, it’s working well, and I was pretty good at, but it was all window dressing, and you know, it. I’ve had I’ve got friends who are photographers now, and I talked to them and they say, you know, photography is an art and it’s Yeah, I mean, I guess it is. But it’s also kind of a mechanical thing. You know, you take, if you take 10 photographers and throw them into a room and give them all the same project, they’re all going to kind of come up with the same image and at that time that I was thinking about that kind of the limitations of the medium. I’m not trying to offend the photographers out there cuz I’m sure there are people who think quite differently about it, but, but I was looking at illustrators and what they were doing and painters as well and you know, the options that you had, you could have 1010 illustrators and give them a project, they’re all going to come up with something quite quite different. And I know that that was really the thing that was always in the back of my head, if I ever get a chance to do you know, be a painter or an illustrator, whatever, doing things with my hands, as opposed to doing things mechanically with a camera, that’s where I want to be

Eric Rhoads 12:40

What led you out of that situation into painting? I assume you didn’t do any painting the whole time?

Lon Brauer 12:46

I did. I did. In fact, I had a good client. I had a client. I did a lot of medical supplies. I was photographed I had a client that I was with for about 10 years. I was a freelancer so I wasn’t connected with them, but I was their only shooter. I was doing Oh, they had, it was all throwaway stuff. So it was tubing and syringes and needles and chest drainage and urine bags and all these kinds of things and everything had to be photographed. And by the time we get through their full product line, then they’d have to do it again and there was but they also did trade magazines and and convention displays where they would have the you know, they have what they call the beauty shot of your a bag. And you know, you have to you have to know how to do that. And but but the backgrounds for these things, you know, maybe it’d be tubing, but what I would be able to do they allow me to do is create a piece of art to go behind the tip. It’s just tubing, but you know, there would be some maybe a an image of how it is used. I know I did a series of backgrounds with a whole series of products, and it used my oldest boy. He was eight or nine at the time, I think and I photograph And it was a call what was it was it was a, what was for chest rays. So you have it, you know, you have to actually cut a hole, you know, side between the ribs and you run this to bid for pressure and so we had the product name would sit on top of this drawing that I made of him with you know, there’s an anatomical drawings and all this sort of thing so, so it gave me an a kind of an eye a way to marry the two disciplines. And it just, it was a way for me to you know, keep a hand in, you know, in in the art field that’s in you know, painting drawing, if you will.

Eric Rhoads 14:39

So how did you make the transition from made to where you are now

Lon Brauer 14:41

if it was made for me, the you know, when everything went digital in around 2000 you know, I could see it coming and I thought, I don’t know if I want to do this and because I’ve been shooting with film, and that’s all I knew, because I didn’t Anything when I get when I started. And so I learned everything on the job and the only thing I knew was shooting with a with an eight by 10 camera. So I’m, you know, I’m working with large film. And in fact, when I see somebody with a 35 millimeter camera, I’m thinking, what is that little thing? You know, it’s just it just, I had no, no relationship to it at all. But as when things start going digital, I started getting these calls from my clients. Most of my clients were manufacturers, and they would call me and say, you know, Mike in r&d now has a camera. And I knew what that meant. That meant that, you know, the mic, who’s probably somebody’s nephew says, you know, I’m working here in r&d. I’ve got a camera, I could do this cheaper. I wouldn’t have do r&d anymore. I could be their photographer. I could take batters. Yeah, yeah, exactly. Anybody can take a picture and you know, and so, little by little things just kept getting less and less and, well, I can do one or two things I could I can fire up and try to get you know, I’m gonna have to get more equipment. You know, I’m gonna have to get somebody do Because they were not only not only did you have to then do the photography, but they also wanted you to do pre press, which is you had to take, now you shoot the image, then take the image and prepare it so it can go to the printer as opposed to the old days when the printer would take care of that. I thought I just not wanting to gear up that way. So I thought, I think while things are kind of in flux, I’m going to start painting again. So that’s what I did. And I had space. I had a large space downtown St. Louis and and I certainly didn’t need it for photography. I mean, I hadn’t I still had jobs going but it just didn’t need that kind of space, but I had space to paint. And that’s when I started you know, really trying to learn the vocabulary again, pull the paints out and see what I can do. I had a bunch of hollow core doors. And what I would do is, you know, it’s a great surface them they were they they were down in the dumpster and I pulled them out, cleaned them up and put you know just slow them down. But it gave me a nice hard surface. Just play around with it and I was smearing paint this way and that and doing drawings and kind of rely on stuff I rehab is all figurative work. But it was all conceptual, if you will, because I didn’t have a model in front of me. And just to get, you know, just get my hands dirty again. And, you know, started getting into, you know, I would submit, I submitted a few things to some local shows, got in and won some awards and made some sales and I’m thinking, maybe this could work. But I didn’t give up everything else. It was like one just sort of faded away as the other one was getting, getting built so

Eric Rhoads 17:32

And that’s an old story now in the sense that the whole digital revolution changed everything for photographers, or graphic designers, even free Australia, everything, everything changed as a result of that.

Lon Brauer 17:43

Well, it’s like, I’ve got I’ve got I had a friend, I haven’t talked to him a long time as a typesetter. What do you do with what do you do with a typesetter? You know, that typer I was I used to do a newsletter for one of the for the photo organization as MP in St. Louis and You know, every month, I’d have to go over him and I’d say, Okay, here’s all here’s all here’s what I got, can you put it in the galleys, and he would send it back to me and I would actually, you know, it’s waxed on the back and you put it down, you put it all together all by hand. That’s all gone. And not only that, the, the guy that I used to use, he was the photo lab that I used to go to where they did all the transparency, film processing. You know, it all went away. And now you can’t buy film. But you got it. Yeah, you got to have some connections, we’ll get filmed Polaroid gone. And you know, it just changed. And I think it changed so much, much faster than what people anticipated we said was going to happen. And then in that course, when you put Photoshop and you know, I still use I still shoot a little bit nice, and I use Photoshop for everything but yet, you know.

Eric Rhoads 18:50

So in terms of the whole plein air thing, how did that begin for you?

Lon Brauer 18:54

Well, that happened around Well, in 2010, I think was 2010. I had a client He was I was doing some small photo jobs or he was doing a brochure for a chamber of commerce for a small town just west of St. Louis, out in the wine country. And he said, he called me said, Hey, I got this job. If you’re interested, there’s no money in it, but they’ll feed you. And I said, Yeah, okay, I’ll go out. And it was out at a winery said, you know, they’re doing this thing called plein air. And their painters said, Oh, that sounds interesting. So I get out there and there’s, it was supposed to be a sunset paint paint out, and I got there three in the afternoon. And there’s painters everywhere, you know, they’re sitting in the fields are standing, they’ve got easels, they’re painting, and they’re drinking wine. And I thought, and I walked around and I was doing just kind of what they call running gun shops. It was just, you know, just shooting a bunch of stuff. And then the client would pick three and put it in a brochure. I thought I could do this. So So when it comes around next year, I’m going to do this because I didn’t know anything about the name of plein air world. And so I did, and the next year I did it and did painting, do pay Three days was actually the same location. And, you know, I won an award, I sold it, I’m thinking this is great course that, you know, it’s an everybody’s doing plein air painting because it’s so easy. And I realized, no, that’s not quite the case. But but from there, I just, you know, I started looking for more events, and, you know, and then start finding out how to jury into events, you know, and and, or how to submit to jury and then I got in and smaller events, and then you know, you just keep looking, okay, what’s the next step up? What’s the next step up? And I really did see it as a ladder, you know, how can I get, first of all get recognized by my peers? And then how can I get recognized by judges and how can I get recognized by collectors and so on and so forth? Maybe not in that order, but you know, that sort of thing. So, what year was that first, that first St. Louis? That was 2011. So I’ve been doing this for about 910 years now. And You know, my, I did an event in camp Hill was camp Hill, Pennsylvania, it’s just on the other side of Harrisburg, and they don’t do it anymore. But I went there. And that was kind of the first one where I realized, if I want to make this thing happen, I got to I got to go to as many events as I can get into, and just be a workhorse. And that’s, that’s the approach I’m going to take. And that’s what I did. And you know, and the other thing too was, I was doing a lot of work and it wasn’t a matter of well at first it was just making I was making yellow green paintings like everybody else. And I thought I’ve got to set myself apart from everyone somehow or other you know, and and how can I do that and how can I make them and like I said, I’m primarily I still consider myself a figurative artist. How can I make landscape be interesting to me and I found that I make it interesting by Painting the things that I want to paint, which is usually an object or, you know, some something that is isolated in the center, which basically is a portrait of something other than, than a human being. And, you know, so I playing that game trying to figure out how can I, how can I do this and really, really, really enjoy it.

Eric Rhoads 22:21

And the result was you started winning all these awards?

Lon Brauer 22:24

Well, yes, and no, you know, one of the things I found was I, you know, I kept going back to what I knew, and what I knew when I was, you know, that’s a long time ago, then at that even at that point, when I look back, what do I What was I doing in school while I was doing things like, you know, kind of coming back to the abstract expressionist, you know, it’s not, not not necessarily polished, but kind of like polished and you know, where I’m throwing paint and I’m scratching paint and I’m using sandpaper and, you know, trying all these different things. And I found that I needed to keep it within a certain realm because number one, they the Get juried in, you have to, you can’t go too far off off the rails in order to get into the, to the event. And then once I got into the event, we can’t go off too far off the rail if your intent is to either win awards, or to sell, so I was playing kind of the conservative card if you will. And, and in not doing things as as, as as bold as I would really like to that didn’t get me anywhere, it really did because I was just part of, you know, many on wall, I thought, well if I’m not gonna sound like a win I’m just gonna have fun with it and just go ahead and just start throwing some some interesting things on the wall. And I think that so that, that, that that lack of success in a way that I was getting into the show, so that’s success but but but the lack of selling and awards to begin with, kind of gave me a freedom to to to try some new things. And then to Look at it a little differently, how can I play in this genre? And yet, stretch it, you know, push, push those boundaries, push those edges. And, and I think it what it did was it gave me an opportunity to be true to what I want to do, as opposed to, like I said, you know, muddying it up so that, you know, I can play I didn’t want to play to the audience, Does that ever really get you anywhere anyway? Not really. And what was what? What was the big lesson in all of that? I think that I think that the very fact that you, you know, that I felt that I needed to be true to experiment. If there’s something I want to try to do, I’ll do it. Now. I still fight that, but I’m at an event and I’m thinking okay, I’m going to go I’m going to do this. I’m going to I’m, you know, I’m getting an example. Well, here I’m right now I’ve been doing a lot more drawings in the in my paintings, you know, style a painting but I’m coming back in them with vine, charcoal, or oil sticks, or whatever it might be. So there’s more drawing linework in there scratching it down. I haven’t taken a standard anything yet, but I’ve considered that. So these kinds of things that are kind of non traditional, and those kinds of things. You know, it’s, it’s, it’s risky to do that, I think, because you can easily be Yeah, that’s interesting, but do it does anybody really want to look at that? So, so what I can find myself in the trap of, you know, I need to pull us back a little bit because yeah, sale would really be kind of nice. And I I’m so I have to fight that with myself. You know, I have to to have two minds. But, but I but when I think of some of these experiments that that, you know, I maybe can’t pull the trigger on it at an event I will as soon as I get home, I’m on it. And so my studio time is really important in terms of of exploring those two to a different level. So that when I do then go back out, it seems very natural to me, you know, if I’m going to, you know, one of my favorite tools, serrated steak knife and I use a lot use that a lot for textures and ends and, and certain kinds of contour lines and that sort of thing and I use it all the time. It’s, it’s, it doesn’t seem unusual for me to pull that thing out. You know that that to me is normal. You know, and but you look at, you know, the wall stuff on the walls, oftentimes, you’re not going to see that kind of thing.

Eric Rhoads 27:26

…so that you’re walking that fine line between being true to yourself and being true to something that’s going to sell. That’s always a dilemma for artists isn’t it?

Lon Brauer 27:36

I think I think it is, you know, I’m obviously we we want to make sales because, you know, we need to pay pay for our materials and you know, I’m kind of semi retired I would say now, but I, I like the income and you know, with things the way they are right now, my season’s been kind of thrown into the dumpster and you know, it’s, it’s tight. But, you know, the problem is though, as soon as you start thinking about, you know, what’s the customer gonna want? What’s the gallery gonna want? Or what is the, you know, what, what is the judge gonna want, you start making compromises and you end up with a painting that you can’t feel really good about. Because you know that you’ve watered it down. I played that game when I was doing photography. I mean, it’s commercial photography. So I have clients. And you know, I’ve got a, you know, there’s a, there’s a client, account executive, and there’s a creative directors and an art director, and there’s me. So it’s got to go through all those people. I got to read all those people’s minds. So that in the end of what may have started this really exciting project ends up being, you know, it’s got all these compromises. I don’t want to play that game. I really don’t. I want to be able to make choices.

Eric Rhoads 28:52

And so what is your best advice for artists in that scenario, because they’re always playing That issue of do I paint to sell? Do I paint what I love if I paint what I love and it doesn’t sell, I can’t paint anymore. Where do you find yourself?

Lon Brauer 29:10

I tell you, honestly, money aside, and I know that that’s a big, big aside, I, you have to paint what you want. And you have to paint it the way you want it. And I think you can find yourself and I know, I know some people and I may be in the same boat is that maybe I’m not, you know, maybe this planner thing is not my bucket to stand in. It’s, you know, it’s, uh, you know, you start asking yourself, Well, okay, I want to do maybe I want to do figure and I want to do conceptual figure and maybe I want to do, I don’t know, fantasy or whatever it might be or maybe I want to do graphic novels, and that’s what I really want to do. Well, you know, that’s, that’s fine that but that’s a different that’s somewhere else. And you know, and so, you know, with the plenn air thing in my wife asked me this all the time, she says, Do you really want to do this? And I said, Yeah, I do. Because for you know, planners, number one, I’m outside number two, I get to travel number three, I get to stay at somebody’s house and, you know, and they feed us like crazy. And I got good friends and, and I’m making a lot of paintings. And as as particularly the last two or three years, the the, I think there’s a there’s a movement towards when called avant garde, but more edgy stuff. Not everybody’s doing it. There’s, you know, you’ve got I think you’ve got a bigger I think you’ve had a much more interesting mix of work in in most events now than you had. There’s definitely a trend there’s definitely a trend in that direction. There are a lot more people we’re getting a little bit more abstract and in the way they’re approaching and right there. So it’s a good thing. Well, I think it’s a good thing because, you know, I think, you know, because we do we do rely on on on the collectors and the you know, they’re they’re an avid group, they’re just you know, they’re just so excited about having this there. But if if everybody has kind of, there’s a homogenous look, then then you’re only gonna get the collectors who are interested in that kind of work. And, you know, then we get young people in, and we can’t always have the retirees buying stuff we need to get the young people in, and they’re going to be looking for more contemporary things and more cutting edge, if you will. So, I think if if people know that I’m going to go to, you know, the gala on Friday, and I’m going to go there and I’m going to, I don’t know what I’m going to see, I really don’t know what I’m gonna see because, you know, the events, you know, if they, you know, if they have a nice mix of artists, there’s going to be a variety something for everybody. And I think that’s, that’s going to widen the audience. I think it’s a good thing.

Eric Rhoads 31:48

So, yeah, well, I can’t I don’t have an opinion. You know, me. I’ll never have an opinion about anything. No, of course, I Well, I think the the issue is that everybody’s got to do what’s They feel, you know, and and some people paint, you know, leaning abstract, because that’s what they feel some people leaving tight, nameless people in the middle, you got to paint what you love. I think first and foremost, I think if you don’t do that, then you’re not being true to yourself. Now, I do have a line that I’ve oftentimes used in marketing training, and that is that if you, if it’s a matter of making a living, and you have to clean toilets, I’d rather be painting something even if it’s something I’d rather not paint because at least in that scenario, I’m painting at least I’m growing. I’m learning I’m doing something.

Lon Brauer 32:35

Well, I agree with that. Yeah, I think that Yeah. And which gets back to your question, your original question is, yeah. And, and I have, you know, I was doing art fairs for a while, did that for about six years and kind of concurrently when I got into the plein air thing, and because I thought, well, I’ve got landscape paintings, I can put them on a wall somewhere. And I started doing that and I had, I had just enough success with it that I broke even make some money. I actually made some money. I didn’t make a lot of money. Because it’s it’s just a different audience. It’s a different world. It’s different. But was I going with that? Oh, I started doing a woman came in one time at my booth. And she said, she said, You know, I held these these landscape days, I was telling her the plein air, she didn’t care, because that audience doesn’t care. But she said, you do think bigger? And I said, Well, I can. I think the biggest thing I had was maybe 16 by 20. I said, What are you talking about? She said, Well, I’ve got this wall. Can you do six feet? And I said, Yeah, I can do that. And it was it was done in Texas was down in Dallas. They’ve got one. What is it because they know the name of it now. It doesn’t matter. I had two two shows in Texas. They were back to back both of them Dallas in Dallas or one South was north and a week in between. So I thought you know, I’ve got this weekend between we’re just gonna be hanging out. So I went to, you know, went to Home Depot, bought some panels, two foot by four foot panels and put this thing together in the parking lot. The motel and I bought a bunch of paints and, and I did these, they were landscapes, they just all memory stuff, kind of, you know, kind of layered and they had depth. You know, there was a foreground and middle ground and the background was a sky, but they were but kind of conceptual, but very decorative. And I did, I must have done 15 of those and sold them. And I didn’t really by the time I got to that point, I thought I don’t want to do this import. And I didn’t have to, but if but uh, you know if I really needed the money if that’s something that you know, yeah, I’m changing. I’m still painting and I have a client base for it. So this is one of the issues if some friends of mine back east Vermont area. They’re always up doors painting really, really big. You know, they have these Cape Cod easels and they’re painting 30 by 40 on location, and they they laugh at me because I’m painting a nine by 12 In the same amount of time that they’re painting a 30 by 40 and they said how can you make any money if every time you’re just putting your your small paintings out there? Do you have a feeling about that? Because you tend to paint larger even in the plenary Yeah, yeah, yeah, I do I do because number one, it’s not a gimmick, but it’s, it’s kind of fun to be able to do it. So I like working big because it gives me because I use big brushes a lot of paint and I can move around quite a bit. And I like the scale of big paintings. But I don’t really be honest with you I don’t have a handle on what people want you know, I do get you know, sometimes people will come in say, you know, I you know, I just can’t put that I just don’t have a bunch of all space and so that you know, there is that that practicality about it. And then other places I’ve been in locations where they say can you you know, wish it was bigger because I got that big space you know, then so it it and then you get into situations of you know, your collection. There’s what kinds of houses do they live in? How much wall space do they have? You know, you hate to be selling paintings because it goes with a couch or fits on, you know, fits between the windows. But that is part of it too. So, I know that answers your question or not. I do small paintings I like doing small paintings and I think a small painting can have just as much validity and and it can be as complicated or as complex as a large painting maybe even more so. I when I’m working different sizes, I’m not really thinking about the size. If you know I do small paintings occasionally, I might get stuck on big paintings and because it’s it’s you got a lot of acreage you got to cover and sometimes I’ll think well, you know, let’s let’s do a series of listeners. So small stuff, just to kind of go that way. And I’ll do that till I run out of steam and then I’ll go back to the big things that are all bam. Back and forth. So, you know, again, you know, if you’re thinking about what the collector is going to want, that’s, that’s all there things, I think, if if, if everything’s equal, I think, you know, the artist really just has to paint the size that feels comfortable to them. You know, if they choose to do small because they like doing small, that’s, that’s great if they’re doing small because they’re afraid of big that’s, that’s a different that’s a different issue. You know, that, you know, if there’s if there’s a fear or, or a situation where they, you know, they don’t have the knowledge to be able to do a large painting and that’s why they’re not doing it, then that that’s maybe something that needs to be addressed.

Eric Rhoads 37:43

So that’s something that I find difficult I find it it’s a lot different doing a large painting. Not only is it of course, covering more real estate, but the idea of something different about when you go large. Do you have any tips or ideas for people when they’re used to painting small What they can do to get a little bit more comfortable or how they have to do things differently?

Lon Brauer 38:05

Well, number one, you know, it is bigger. But I think you have to, there’s a fear of moving to a bigger painting because I think, I think with a lot of people, when I do workshops, I see this all the time, they want to work small because it’s almost like when they’re in a room with a bunch of people, they want to sit in the corner, you know, they want to be as as they just don’t want to be bold or you know, the Tim it’s timid, it’s just be timid. And, you know, honestly, if you if you got a bigger panel, get bigger brushes, and squirt out more paint and you can, you know, it’s it’s not that hard. It’s but it’s that first step of doing it. I look at you know, I’ve got I’ve got a painting I just finished the this morning. Maybe it’s finished, I don’t know, but it’s 30 by 40. And it’s got to figure and, you know, when I was blank canvas, something that’s gonna take a lot of pain. It’s going to take you know, you kind of walk your way through Without having done anything at all, you kind of look to the end and you work your way back anything. I want to do that. And but it’s you just kind of have to take a bite at a time and just start throwing paint on it and, and that sounds easy. I know it’s not it’s not quite that easy. But I think the way to work larger is just get a larger panel and start working larger, you have to get comfortable with it. And at first it’s not nothing you know, the first time you do anything, it’s not comfortable.

Eric Rhoads 39:29

Yeah, with your brushes and…

Lon Brauer 39:31

Bigger brushes are the key. I use two x brushes and three inch brushes. But that’s the way I paid. I mean, it’s and that’s the other thing too, that if you’re doing very tight traditional work, which most people want to do that. Okay, here, let me back up a little bit. I get people all the time in workshops, particularly or they they want to do a workshop with me and they’ll say, I want to be loose like you and I. Okay, we can do that. That’s easy. You will start with a bigger brush. We’re going to do Paint we’re going to get a bigger panel and all this kind of stuff want to do, but they keep falling into this trap of doing tight, tight little tiny little paintings because their experience is is is limited their experience is photography. That’s what they know. And even though they want to break edges and they want to, they want to simplify shapes and patterns and all this kind of stuff in their head, the brain is working against them. And it says you know that it needs to look like a photograph and even though they’ll say I don’t want it to look like a photograph, they that is how it is they’re driving.

Eric Rhoads 40:36

Yeah. So how do you break them up?

Lon Brauer 40:39

Well, one good exercise I use a lot is okay, when I have a student come in, when i when i people in workshops, they often will start at noon. I know you’ve seen this and you’ve probably done yourself I know I have where you start a painting that first 10 minutes is you know it’s it’s really pretty fresh. It’s it’s spontaneous and You know, there’s, there’s, there’s some really wonderful, you know, great stuff going on. And then they, you know, the student will then take it and and basically drive it into the ground because they’re trying to take it someplace. But it’s, you know, if what I’m what I try to do is have the students capture that that freshness and and keep it and not over, you know, take it beyond that you know and the way you do that is you have them paint something and you give them a timeless you know, and it has to be a short time limit so you know, the you know, the first thought was well I can’t do a painting you can you just do it and put it on the floor and forget it just keep doing it. I did with my my wife wanted to learn how to do she wanted to do quick thing she’s she’s an artist, she’s a fiber artist, and she said I think I could paint so never painted before and I said okay, I’ll teach you how to paint we’re going to do a total immersion thing. And I’m going to teach you how to mix paint and I’m going to you know, show you some something about Vegas, but I’m just going to show you and I’m gonna give you a brush and you’re gonna put it on there. We cheated in a course of about three months, she did quick paints at Eastern Endor county and down in Texas. And but I said, here’s the deal, because I gotta do my thing, you’re gonna have to do this on your own. But I said, here’s a bunch of panels, you got 10 minutes on each one, just paint the same thing over and over again. So you know, in 10 minutes, it’s true chip chip chip in throw it on the floor. I said, at the end of that end of an hour, you’re going to six paintings. This got to be a gym in there somewhere. And now is that the best way to learn, I don’t know, but it does give it gives a student an opportunity to see something that they would have dismissed and covered up and to see it as a finish or as a as a finish or complete but, but it’s got some sort of, it’s got some good bones do it and you know, so it seems to work pretty well. But what you Gotta give them you know, it’s just a matter of, you know, just let the painting do the work and not not, you know, not that try to drive it to someplace where, you know, some other expectations, that’s that’s oftentimes, you know, for a lot of people, they don’t have the skill level yet to get there.

Eric Rhoads 43:19

Well, I think if you give them examples, you know, I, one of the mistakes that was made when I was learning to paint is that I didn’t really have anything to rely on other than photographs, as you said, you know, so I didn’t, I didn’t know a lot about art. I didn’t know a lot about painters. And finally somebody came along and said, Okay, I want you to before you come to this workshop, I want you to pull out, you know, 10 screenshots of 10 paintings that you absolutely have fallen in love with. And then what then the instructor pointed out to me so you realize how loose This is. And look at this. There’s nothing photographic about this. And so it was in a way it kind of gave me permission to realize it’s okay to get loose because there is that tendency driving us towards you know, photographs. And of course, people will come up when you’re painting and they’ll go, Oh, it looks just like a photograph which of course you want to wring their neck. But but at the same time, it’s a, it’s a clue to you that maybe you need to, you need to loosen up a little bit.

Lon Brauer 44:21

Right and, and to tell someone to loosen up is that’s, that’s not really enough information to because they probably know that or they, they want it to be something else. But there are certain things you know, and like I said, I break edges, just breaking edges, you know, it’s a small thing. You know, running a learning brush through, you know, two different areas that you know, across an edge and that can that that breaks it up but but it’s sometimes there’s there’s there really needs to be more to it than that. You know, you’re talking about, you know, photographs and you know, the the the people will use photographs But I think they use them in the wrong ways. I think they’re, they’re a great tool to be able to learn. You know, when we look at photographs, well, I do I do pay from photographs. Well, here’s the deal, you know, the, I don’t know, let me let me caveat first when i when i do other vet all events have rules and you know, and they’re their number one rule is no photographs, which is fine. I you know, that done, you know, I don’t really need photographs for for doing the kinds of things that I do at events. But if I need some information, sometimes a photograph is a good good tool to have it, you know, there’s three, three things that we reference when we paint we paint from, from direct observation, you know, things in front of us, we can use photo photo reference, so that could be a drawing or the study, either we did or somebody else did it. You know, there’s all kinds of printed references which you’re looking at. So they, in a sense, they are direct observations. Well, and then the third thing is, which I think is probably the most important is memory. You know, what we’re doing when we’re learning how to paint is where we’re building a memory of, of things we’ve done, and, and ways of doing it that we can then incorporate into what we do when we go out into the field. And, you know, I think it’s a Robert Henry was his book. He talks about, you know, it would be ideal if we could, you know, if you were, again, using a figure situation as an example, they said, what I’d have my students do is go upstairs to another room where the model is, and I’d sit and have, they’ve got 15 minutes to look at the model and to make sketches or any kind of notes they want, but then they come back down into the into the studio and actually make the painting from memory and that’s hard to do. But that’s kind of what we’re doing. You know, working from memory. But back to back to back to the photographs. The value of the photograph, I think, is the fact that if you understand what a photograph is, you can use it I think more efficiently. You know, yes, it doesn’t give you all the information that you might get if you were standing out in the field in terms of values and colors, and that sort of thing, but it does give you a sense of pattern and shape. And that is really, what’s one of the key things to what we do and I think gets gets overlooked. You know, if I, if I had a photograph of a tractor, and I handed it to you and ask you what, what is this, you would say? Well, number one is easy to say it’s attractive, which is not are you say it’s a photograph of a tractor, which it is, but it’s really not that either. It’s a piece of paper with light and dark patterns on and it’s those light and dark patterns that we need to key on. So we’re not painting a tractor we’re painting light and dark patterns. And that’s the way it is with anything. We don’t paint what’s in front of us. We don’t paint grandma’s house, we paint Light and Dark Shadows that when put together, your brain says, Oh, I understand that I see that pattern. And I’ve seen it before. That’s grandma’s house.

Eric Rhoads 48:10

So you’re really, looking at that as abstract shapes.

Lon Brauer 48:14

And that’s all it is. I mean, painting is abstraction. And so it’s photography for that matter. It’s not real. I mean, they, you know, we think of photography is real. It’s not real, it’s an abstraction of, it’s just, it’s just like patterns. You know, the word pareidolia…

Eric Rhoads 48:31

Never heard it.

Lon Brauer 48:32

Pareidolia is when you see the man in the moon or Jesus on a piece of toast, it’s, it’s, you know, we see we see a dragon in the clouds. We it’s pattern recognition. Yeah. It’s pattern recognition. We look for that, you know, it’s a, it’s a survival mechanism. We need to know that, you know, we’re in the Serengeti plains, and we’re walking around and we see something we need to know whether that’s a lion or a rabbit, so we can respond to it. We need to know it immediately. And so we are Marines are icy just like a camera does. It’s just like dark patterns that come in and it gets sent to our brain and a brain, then we’ll look and see if it’s got a symbol for that. And if it sees, you know, it says, well, when those light and dark patterns are put together in that particular configuration, it’s a tractor. And it’s, and it’s, you know, it’s the same way when we’re out in the field. You know, you when you’re looking at whatever it is, you need to be able to key on those light and dark patterns. And that’s hard to do. Because your brain is wanting to over override you and say, Well, I know what that is. Therefore, let’s let’s get at it, because it’s in its efficiency thing that you need to somehow learn how to shut it off. You know, when I when I was teaching figure drawing, I had a student one time, and she was in there, she had never drawn anything. And here she has a figure drawing class and she was really lost and she just couldn’t do it. But we tried to persevere and we had one day where the model actually Had reclining on the dais. And she was right down kind of looking at the model from the top of the models head. So you had these overlapping forms you had, you know, the head and the breasts and belly and knees and feet, and whatever it is, and they were all stacked up because it was foreshortened. And she did really well. And the reason she did well is because she had no frame of reference. She had to respond to the shapes. You know, it’s like taking a photograph, you know, and turning it upside down, you know, the right side of the brain thing. If you’ve never done that, you need to do that. Because it will, it will just blow your way out, well, good. You’ll be able to respond to that image, or do it all the time whenever not so much with a photograph, but when I am…

Eric Rhoads 50:45

When I have a problem with a painting, I turned it upside down.

Lon Brauer 50:49

So that’s the same, it’s the same thing because when you turn it upside down, your brain still knows what it is. But it sees but it has to not only look at the positive but it also has to look at the negative and sees all those shapes with the same kind of with the same hierarchy. So remember, they’re they, they all have the same value. So, you know, that little negative space, which is a triangle, you’ll see it as a triangle. If it’s upside down, right side up, you won’t see it. Because your brain says, It’s not important. I don’t need to see that. And, you know, that’s, that’s just the way it, you know, that’s the way you have to learn it, then, you know, and then of course, you know, and you and actually if you, you know, if someone’s painting from photographs, if that’s their only source is upside down all the time. There’s no reason why not to if you know, a camera, the image that comes into a camera is upside down, you know, we see prints from you know, the old film days you see a print, you know, comes back from Walgreens, it’s, you know, you’re actually looking when you look at that right side up, you’re actually looking at upside down. So that’s not how it was captured. So you can’t turn you can’t turn. You can’t, when you’re out in the field. You can’t turn the world upside down. Unless you have a camera obscura, you can but if you don’t But But the thing is, but my point is if you can get if you can start understanding that that image is not the thing that it is, it is the patterns that you know the light and dark patterns and understand those shapes. You know, like, again, when I do I do a lot of head studies and when I do, you know, the shadow that is created around the eye eye socket, that has a certain shape, you know, if there’s a light from above, it’s going to it has a certain shape, if you put that shape in, it will describe that and again, it’s a bit of a symbol, but it’s, you know, it will work every time. And same thing when you know, you know, a doorway, you know, a dark doorway and a light in a building. You know, you put a little dark rectangle on a on a white field with a Gable hits a house with a door it’s it’s, we you know, we we see it we what we’re trying to do is communicate we make a painting we’re trying to communicate to the viewer If it’s whether it’s ourselves or somebody else, so they look at it they go, I seen that before I understand it. I mean, that’s, that’s what representational art is all about. It’s apparent All right,

Eric Rhoads 53:14

I went to a workshop recently, I won’t mention the name of the instructor, but he said the opposite of what oftentimes people say most people say paint what you see. He said, paint what you know. And he said, for instance, I know that I’m seeing a cool shadow, but I know it’s gonna work better as a warm shadow. And so he you know, and the same thing with shapes. He said, you know, the same thing with you know, every eye socket looks approximately like this. Every skull looks approximately like this. You have to capture that likeness, but you have to get, you know, a sense of what people know. So it will represent itself as what you’re trying to represent.

Lon Brauer 53:49

Well, I think there’s, I think there needs to be a balance and this was kind of what my my credo, if you will, when I go out. I want to paint I want to find a balance between what I see and what I know. So that means I’m not married to what’s in front of me, however, that’s my reference. So, you know, there’s gonna be certain things that I need to refer to I’m looking at, but, but I’m also, you know, really kind of pulling out things that I’ve either painted before I know, or certain lights and darks or certain, you know, warm colors, cool colors. I know what colors work together. I may not even even know it. You know, I know may not be I’ll tell you, which ones that I use and why not use them? I just know they work. It’s instinctive from experience, you know?

Eric Rhoads 54:34

So as we kind of get to the end of this thing on what we’ve always got a lot of new plein air painters who are listening to this podcast around the world and and I always get the question of what’s the best advice you can give somebody who’s taking up plein air painting for the first time or they’re in their first year. What are the essentials, if you were teaching beginners, other than what you talked about, with the You know, painting a lot of panels fast. What other essentials? Do you really try to nail with these people and get ingrained in their heads early on?

Lon Brauer 55:05

That’s easy. You need to learn the skills, you need to learn the craft. You know, it’s it’s painting is fun, and it’s no doubt but you have to know, you have to know how to use your tools, you have to know you know, if you’re an oil painter, you’ve got to know how much paint to put out on a pallet and and when you don’t have enough you need to know that that’s not enough. And, and a lot of that comes from course from doing and doing. But if you don’t know your, if you don’t know the craft, and it is a craft, and you don’t have the skills of what to do with a brush and how to make different kinds of marks than it really is, you know, to go out and try to make a picture. It’s like It’s like buying a violin and saying I’m going to play a tune. No, you’re not. You’re just you know, we all want that. But, but it’s just not going to happen. You can you might accidentally be It’s something but, but if you sit down and really and I know that people don’t, you know, you always say the start well I don’t really want to spend that much time with exercises and, and but I think it can be fun. I think you know you’re painting with differences that make you know if you’re painting whether you’re just making marks on a page with a brush, I think you know, what I tried to do is I try to instill in my students is enjoy the paint, you know, not not the picture, forget the picture. Enjoy the paint, the quality of the paint, the buttery pneus of paint and how, when you pick it up with a brush, you can push it you can pull it, you can drag it, you can wipe it off, you can put it back on again, and when you mix certain colors, they make a muddy color and but that can be beautiful as well and it’s just, you know, get your hands in there and really appreciate that. pictures come later. In fact, sometimes pictures come and you’re not even planning it. You know, it’s it’s it’s a matter of but you have to be It’s, you know, it takes an entire lifetime. You know, I know I’ve had students say, Well, I’m getting older and I don’t have a whole lot of time left. I’m in that boat too. Yeah, but it’s not it’s not like we’re trying to make a chair and we’re doing we’re gonna keep working till we make a good chair. We’re, it’s, it’s, it’s a, it’s a journey. And there is no end to it until we just until we drop over the strength but strive strive to enjoy the journey. And that that chapter journey, the journey is huge. And I think that’s really that is the endof that. Yeah, that’s my biggest advice, you know, forget the picture. You don’t need the picture. Well, you’ve got a shot comparing yourself to other people too, because there’s always going to be somebody who’s, who’s better. And it’s a bit for some reason. I mean, you know, we know that if you’re a brain surgeon, you have to go to however many school years of school to be a brain surgeon. We know that if you you’re going to sit down at a keyboard board, you can’t just come up and slam the keys, we know that you have to learn that the notes we know you have to practice you have to do all these things. But for some reason we have this thing in our head that well, an artist, it’s all natural. It should be born talent, you should be able to paint a masterpiece right out of the box.

Eric Rhoads 58:18

I don’t know where that comes from.

Lon Brauer 58:20

Well, yeah, and it and of course, it’s, you know that. And that’s, that’s the fallacy that dwells, if you can’t do anything else do art. But it’s no, it’s the you know, I take it a lot more seriously than I think I think most. Well, it’s a serious endeavor. That’s what I’ve always kind of in my head, I think. And actually, you know, this comes out when I was growing up, I’m growing up and everybody says, Well, you can be an artist, that’s a great hobby to have. But when when I finally realized being a painter is is as valuable as being a doctor, it’s a different kind of value, I suppose, or not, but it’s it’s there’s so much intellectual endeavor that needs to go into making a painting. It’s not just, you know, you’re not just setting up your easel and throwing paintings, like we got a pretty picture, put it in a frame, it doesn’t work that way looks like it does for someone who’s been doing it a long time. You know, I’ve done paintings where I’ll go in and I will paint for an hour or two and it’s like, wow, wow, that came about it came about from doing a lot of work. Well I can give you I get a lot of doctors, I can give you a list of doctors who wish they were painters because they feel like their mechanics.

Eric Rhoads 59:28

Many of them, they just get to the point where it’s like, Okay, this symptom, give them this, this solution, and they marvel at what we do, which is why so many doctors are becoming painters when they retire.

Lon Brauer 59:39

Right? Well, painting is is problem solving. I mean, it’s it’s, it’s not making a picture, it’s problem solving, you’re figuring out you’re trying to take this this gooey stuff in a tube and pick it up with a brush and put it on a flat surface and make it say something, whether it’s abstract or whether it’s representational. You’re trying, you’re trying to again, we get back to the pattern things, you know, can we put these patterns together? And can it? Can it then kick the brain and say, Oh, I know what that is. And that’s really kind of cool. That is, that’s, that’s, that’s a pretty complex thing. That, you know, it’s is it? Is it more complex than music? Or is it is it I don’t know, I’m not a musician. I don’t, I don’t sing. I don’t dance it or do any of that. But I know that no matter how much I do have this. In no matter how far I go along. I realize there’s still so much I need to learn. And I know I was talking to somebody yesterday, and we were marveling at how we’ve been painting for so many years. And it’s still a challenge and it’s the chasing of the challenge that makes it fun. But you know what? Getting back to the skill thing, if you can get if any artists can get. If you can get your skill level up to where you know, then you don’t have to think about it. Then you can get past You know, this, you know, I always think about the, the the, the, the kids went out of my head, but if you if you know, if you know how to make the marks and you know, you don’t have to think about every single mark that you’re putting down, you don’t have to think about, you know, what color Am I going to mix? And how am I going to mix that and try to figure it out, particularly in the field. You don’t, you don’t want to have that you want to get all that out of the way so that you know, so that when you are faced with something, you’re working on a painting in the field, and you’re faced with what color is that? You know, you just know how to mix this and this, you know, and if it doesn’t come out exactly the way you say, well, that’s not quite the green, I want it but that green might work. Because I think I’ve seen that green work before I’m going to use that green. And and so you know, it’s it’s it’s getting yourself into a mess and then figuring out how to get out of it and knowing how to get out because you’re making all these.

Eric Rhoads 1:01:55

How do you get there though? How do you get to that point of painting by instinct.

Lon Brauer 1:02:00

There is no painting by instinct. No, it’s it’s no, it’s skill. It’s It’s It’s skill, just knowing, knowing your thing well enough. So that, you know you don’t have anytime that you come across a situation where you, you don’t know what to do. Here’s an example I was doing, I was doing a painting of a Longhorn steer down in Texas and you know, steers a cow, kind of So, and they’re moving around in the field. So I’m doing this, basically a cow with these big long horns and I could get the body and I could get the head. I could not get those horns because I’d never experienced the horns. Not really, I’ve never really drawn the horns, and here I’ve got a moving target. You know, they’re like, staircases going in opposite directions and curving this way, in back way. And you know, and back this way, and I worked on that for three hours. And what it told me was, I going to go back to studio to figure this thing out so that when I go back, I don’t care what that What that that steer does with his horns? I know what they do. And you know, so I don’t have to, you know, I don’t have to struggle on site. It’s just it’s just not, it’s not efficient. I want to know that anytime I don’t know something, I want to know what is what is what is what is the horse and scuffle look like, I’m not real sure what I need to find that out so that I have it in my head, I may never use it. But I need to have that. And I think that it’s that, that, you know, that quest for getting as much knowledge you should be able to paint anything from memory. And now obviously, that’s, that’s, that’s a lofty goal, but the more we can pull out of our head and be particularly to a representational, you know, the more we pull out, the more we know when it’s right and when it’s not right.

Eric Rhoads 1:03:48

You know, so, yeah, what’s what I meant is there was I remember taking photography workshop with Fred picker in the zone system. And Fred said, Look, you I complained We were not going out and, and taking pictures of pretty things or something. And he said, Look, you have to learn to get to the point where you can create any effect any light, any, you know, any sense of what you can do with that camera. You’ve got to get that down before you go out and take pictures because then it becomes an instinct. So it’s not a natural instinct. Yeah, yeah. Yeah, I think I think Well, yeah. And I think another term like, you know, it’s just it’s, it just, it’s just part of you. So yeah, exactly. Well, this has been fascinating. It’s been a very quick time. You’re fascinating guy. You’ve got a lot of great information.

Lon Brauer 1:04:40

I am very, very much enjoyed it’s been it’s been a lot of fun. Any final thoughts for everybody before we say Sayonara. Everybody stay safe and stay well and let’s get back out the painting because it’s sitting at home is just not not gotten it. So I hope we get I hope we can get back out and you know, get back to work. Absolutely.

Eric Rhoads 1:05:02

Well Lon, thank you so much. It’s been a pleasure.

Lon Brauer 1:05:05

Thank you as well take care.

Eric Rhoads 1:05:07

Well, thanks again. Lon Brauer, what a fabulous painter he is. Are you guys ready for some marketing ideas?

Announcer 1:05:12

This is the marketing minute with Eric Rhoads, author of the number one Amazon bestseller make more money selling your art proven techniques to turn your passion into profit.

Eric Rhoads 1:05:24

In the marketing minute I try to answer your art marketing questions that you submit to [email protected]. We also have the marketing minute as its own podcast if you want to look it up. Here’s a question from Amanda Houston, from Cornelius, Oregon. Amanda says how do I evaluate which publication to go deep into? I assume she means advertising. If I want to be in the waters where the money is flowing, which is a term I teach in marketing, which publication will allow me to grow my list of calls collectors and potential galleries, art brokers, interior designers, etc. Well, Amanda goes back to your strategy. You have mentioned a list of growing strategy but for different areas of focus, you’ve said galleries, collectors, art brokers, designers, you need to pick one which is your 80 percenter, which is the one that if you’ve got nothing else you go after that one particular one. I don’t think you should try to go after all four. I don’t think there’s any publication that’s really going to give you all four you know, if you want designers, you might want to spend, you know, massive amounts of money for a page in Architectural Digest or maybe it’s a local designer thing in your community. If you want art collectors, you know, who are looking for representational art, you know, and you want really rich ones. You go with something like fine art connoisseur, but if you want plein air collectors, those people happen to be in plein air magazine. So there’s a lot of different things and you’ve got to kind of decide Which you want. galleries are a low target because you can’t control your career with galleries as effectively. And you won’t get your prices up until you’re in their high demand top tier. Now I’m not trashing galleries, I think they’re a really good idea. But we put a lot of emphasis on galleries, I think earlier in our careers because we think, oh, they’re going to solve my problems. The problem with having a gallery is that if you have only one, then you’re relying on their ability to sell and if they mess up, or they have a bad month or a bad year, you’re going to have a bad month or bad year. That’s why I want to control things I want to control who in how I say who I sell my art through and how I sell it. And that way you can control your pricing you can get your prices up, etc. With a three year branding campaign that’s going to help you because branding helps you get your prices up. It’s going to help you get to galleries, it’s going to help you get in a lot of what a lot of different people collectors and so on. You know, you can reach galleries and collectors through one publication typically like the one that I mentioned. But designers, big world, you know, national, local, the cost to reach them can be, you know, 100 times the cost of reaching art collectors. It just depends on how you want to approach it. So first and foremost, Amanda, get your strategy down. And once your strategy is down, that will make a huge difference in what you decide to chase.

Eric Rhoads 1:08:30

Okay, next question comes from Mark Dickerson in Mission Vallejo, California who says I have a quick question. I know you’ve talked about this in the podcast. I don’t have gallery representation yet. But when I do get a chance to really want them to be my art marketing partner and I want to offer the gallery a percentage of everything I create, even if it never hangs in their gallery. I want them to know we are in this together. How much of a percentage should I pay the gallery for any work I produced that night hangs in there gallery 25% I want to have this figured out. So when I get a chance to partner with a gallery, I’m ready to offer them to be my partner and all of my art. Mark respectfully, why would you do that? I you know, I think that the idea of having a gallery partnership if a gallery sells something for you, typically they want somewhere between 40 and 60% depending on your stature, you know, like if you’re a you’re a high level artist, you might get paid 60% they keep 40% if you’re a newbie, they might keep 60% but somewhere around that 50% area’s what they’re going to pay, but they get paid for what they sell. Now, I’m not suggesting selling around them, but why would you give a gallery a percentage of everything you sell, even if they don’t do it for you? I think that would be folly. Now. I think it goes back to what I said earlier is that a lot of people want to advocate they don’t want to delegate then want to advocate, the idea is you delegate to a gallery and you say, okay, your responsibility is we agree to that you’re going to sell my paintings at this percentage for a certain period of time and and hopefully so many per month, you know, you can’t predict that exactly. But when you advocate, you’re just saying here, take over my career and run with it. And the problem is when you have somebody taking over your career, they may or may not do it as effectively as you want them to. And you know, it’s like, say, okay, you hire a manager, and you say, okay, go do whatever you want to do. Well, all of a sudden, that managers spend all your money and run off with your wife. Just never know. So you’ve got to be really careful about advocating versus delegating. And I think that’s a really important thing to think about. So, you know, typically 50% is what the gallery gets, and I like to have a balance. I think that every artist should have a certain percentage of their work or certain type of their work that they’re doing. Selling direct. And that, you know, some galleries don’t like that. And I understand that. And if they’re willing to give you enough of a good deal and enough sales, then it might be worth allowing them to do that. I know people who do it very effectively, but I don’t want my art to be in one gallery and then sit there for months and not sell, I need those paintings to sell to be able to pay my bills. And so as a result, you want to have something, you know, I like to have balance. I like you know, sometimes there’s hot markets. You know, there was a time when Silicon Valley was really hot, and people were spending money there, there were time that certain vacation spots were hot, and there were other cities that were not. So I like the idea of having my work in an area that’s hot as well as two or three other areas maybe and and that way, you know, and there are also economies that are based on seasons. So you know, like if you have a gallery in Cape Cod, they’re not going to sell much in the winter probably. If you have a gallery in Hawaii there may not sell much in the summer. You know that you’ve, you’ve got a ski resort. Well, ski resort probably is popular in summer and winter. So you got to kind of figure that out. And I like to, I like to spread the risk to at least three and sometimes a little bit more. I personally am only in one gallery. And that’s because I can only produce a certain amount of work because I don’t paint for a living. And I just got a call that that gallery is thinking about closing their doors. And so what do I do now I got to figure out a new gallery to go into, right. So I think you want to make sure that you have control and I didn’t have control in that particular case. Anyway, I hope this is helpful. This has been the marketing minute.

Announcer 1:12:41

This has been a marketing minute with Eric Rhoads, you can learn more at artmarketing.com.

Eric Rhoads 1:12:49

Well, a reminder to get your tickets for the plein air convention. It’s going to be taking place in August in Santa Fe. Yes, it’s still taking place as far as we know if we have to cancel you get your money back Or you can read. If we reschedule, you can push your money to a rescheduled event. I also want to remind you that the plein air salon is going to be wrapping up here at the end of the month, you want to get your entry in at pleinAirsalon.com. And last but not least, certainly not least brand new event. It’s called Plein Air live and it’s going to be taking place globally, a virtual event you can do from your living room, you do not want to miss this is going to be part of the global plein air community. We’re trying to get every plein air painter on earth on this, it’s going to be very cool. And you don’t have the travel expenses and all the other things that go in with a live event. So make sure you check that out. And if you’ve not seen my blog where I talk about life and art and other things, check it out. It’s called Sunday coffee and you can find it at coffeewitheric.com. Well, this is always fun. And we will do it again sometime like next week. Hopefully God willing. We’ll see Are you that I’m Eric Rhoads, publisher and founder of plein air magazine. Remember, it’s a big world out there. Go paint it.

Announcer 1:14:07

This has been the plein air podcast with Plein Air magazine’s Eric Rhoads. You can help spread the word about plein air painting by sharing this podcast with your friends. And you can leave a review or subscribe on iTunes. So it comes to you every week. And you can even reach Eric by email [email protected]. Be sure to pick up our free ebook 240 plein air painting tips by some of America’s top painters. It’s free at pleinairtips.com. Tune in next week for more great interviews. Thanks for listening.

- Click here to subscribe to the free newsletter, Plein Air Today

- And click here to subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue!