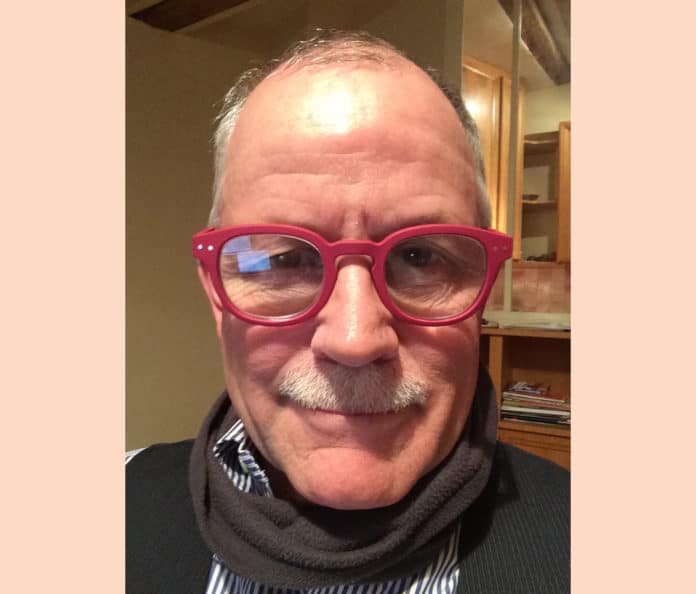

Welcome to the PleinAir Podcast with Eric Rhoads. In this episode Eric interviews Timothy Standring, who is the Curator Emeritus of the Denver Art Museum, an art historian, author, and much more.

Listen as Timothy Standring shares the following:

• Thoughts on painters today versus the painters of history

• The importance of educating the general public about art that’s created with skill, and how to “develop” them

• How to determine that a painting is appropriate for a collector’s space

• His advice for artists who want to develop their work and their careers, and more.

Bonus! Eric Rhoads, author of Make More Money Selling Your Art, shares advice on if you should list your prices on your website, and thoughts on fame versus success, in this week’s Art Marketing Minute.

Listen to the PleinAir Podcast with Eric Rhoads and Timothy Standring here:

Related Links:

– Timothy Standring online: https://www.standringwatercolors.com/

– Realism Live: https://realismlive.com/register-now

– Fall Color Week 2020: https://fallcolorweek.com/white-mountains

– Eric Rhoads on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/ericrhoads/

– Eric Rhoads on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/eric.rhoads

– Sunday Coffee: https://coffeewitheric.com/

– Plein Air Salon: https://pleinairsalon.com/

– Value Specs for Artists: https://streamlineartvideo.com/products/paint-by-note-red-glasses

– Paint by Note: https://paintbynote.com/

– The Great Outdoor Painting Challenge TV Show: https://thegreatoutdoorpaintingchallenge.com/casting-call

FULL TRANSCRIPT of this PleinAir Podcast

DISCLAIMER: The following is the output of a transcription from an audio recording of the PleinAir Podcast. Although the transcription is mostly correct, in some cases it is slightly inaccurate due to the recording and/or software transcription.

Eric Rhoads 0:00

This is episode number 186. Today we’re featuring Timothy Standring, the curator emeritus of the Denver Art Museum, art historian, author, and plein air painter.

Announcer 0:33

This is the Plein Air Podcast with Eric Rhoads, publisher and founder of Plein Air Magazine. In the Plein Air Podcast we cover the world of outdoor painting called plein air. The French coined the term which means open air or outdoors. The French pronounce it plenn air. Others say plein air. No matter how you say it. There is a huge movement of artists around the world who are going outdoors to paint and this show is about that movement. Now, here’s your host, author, publisher and painter, Eric Rhoads.

Eric Rhoads 1:12

Thank you Jim Kipping. And welcome to the plein air podcast. Happy September everybody seems like this summer went by pretty rapidly. This is kind of the year that never was. Things were simply not very normal this year, nor are they now but anyway, the best part for me is I got a lot of painting done more than normal even though I still work from home. It’s a beautiful thing to be able to get some painting done. I am really looking forward to fall and as it stands at this moment, my annual artists retreat fall color week is going to happen live in person. It’s unbelievable. We thought we would have nothing going on in person this year, but it looks like it’s going to take place. The resort we’ve taken over is going to be all ready for it. They’re taking all the precautions we’re taking precautions Of course most of our time is painting Outside, and we’re painting for the first time in the White Mountains of New Hampshire where the Hudson River school painters painted their famous fall scenes. And we have artist Eric Koeppel, working with us and helping us. Even though it’s not a workshop, he’s going to be there. He’s going to show us his favorite spots. And we have a full house or almost we have a few people who have dropped out because of COVID. But I think we have 12 seats left. And if you want to go We would love to have you. And of course if you have to cancel for any reason, because of COVID, etc, we understand and we would give you all your money back so you just got to sign up at fallcolorweek.com All right. Now speaking of signing up, everyone is doing it. Everybody is signing up for realism live. We had done plein air live, it was a huge success. We decided by by noticing that people were doing a lot of other kind of painting too. We decided to create a realism conference this coming October. And it’s an incredible lineup and it’s about the topics you want to learn. It’s got landscape Studio landscape plein air painting, of course still life floral painting figures, portraits, color theory, so, so much more all from very, very top artists. And we’re able to get these people in this kind of a lineup this year probably because of COVID. That’s what I’m thinking anyway. They’re going to be more or more announced soon, but Kathy Anderson, Juliette Aritistides, Stephan Baumann, Tony Curanaj, Marc Dalessio, Rose Frantzen, Dan Gearhartz, Dan Graves, Cornelia Harris, Victoria Herrera, Joshua LaRock, Jeff Legg, Kathy Odom, Graydon Parrish, William H. Schneider, Daniel Sprick, Jean Stern, Connor Walton, Peter Trippi, and me, of course, is your host. It is four amazing days and it’s all virtual. So you can watch from the comfort of your home and we have international components. We got people watching from 30, 40, 50 countries, we’re going to have teachers from other countries, and there’s a fifth optional For beginners and including on all of these, there’s going to be interaction so you’re going to be able to interact with one another interact with, our suppliers and vendors and sponsors. So make sure that you visit realismlive.com and get that seat booked because the price goes up to hundred dollars as of September 30. You want to make sure you get in for that. Coming up after the interview. I’m going to be answering your art marketing questions in the marketing minute. But first, let’s get to our interview with Timothy Standring, curator emeritus of the Denver Art Museum and also at plein air painter, Timothy Standring. Welcome to the plein air podcast.

Timothy Standring 4:38

Eric, it’s so great to be here with you.

Eric Rhoads 4:41

I think this is going to be a real interesting podcast because you’re the first person that I think I’ve ever interviewed that blends a whole lot of worlds together. You are the curator Emeritus from the Denver Art Museum having recently retired. Congratulations. You are an art historian. You’re an author and expert about certain artists, and you’re a plein air painter. So this is going to be a lot of fun.

Timothy Standring 5:12

Well, I hope so. And I hope so for your listeners that I’ve found that the to go hand in hand and actually my own practices informed how I write about artists and art history.

Eric Rhoads 5:27

I think that’s a really great place to start because one of the things that really perturbs me at it is that so often you go to an art museum and you’ll read what a curator has written about a particular artist and what that artist was thinking about or what signals he or she was putting into her paintings, and a lot of these people have really great backgrounds and really understand Art History, but most of them have never painted. And so, sometimes I kind of feel like they’re just trying to fill space. How do you kind of bridge that? What was it about painting that really helped you see things from a different perspective? Or did it?

Timothy Standring 6:19

Well, I really wanted to understand how, I want to understand how artists make their paintings. And if I’m so, for example, with Degas, he used a great deal of repetition. He had ads affirmation is and cancellation in terms of his mark making. He was he was all over the map and I wanted to understand the basis for that and how that informed him in his His works of art his past sells his oils in his drawings and how that really worked throughout his entire career. The same thing with old master painters with in addition to 19th century painters and even 20th century painters, so I’ve written on contemporary artists, Dan Sprick, Keith Jacobs Hagen, Scott Frazier, T. Allen Lawson, and Andrew and Jamie Wyeth. And I spent an enormous amount of time just lingering in their studios reading everything that I could, but I still want to get to the heart of, of how they approach painting and what that meant to the final picture. Remember, Ben, Shawn’s book shape is some form of content, which still resonates with me. And it’s so true because what An artist how an artist constructs painting really has something to do with the meaning if they’re bringing across and, and I really wanted to deal with that I’m, except I allow different kinds of narratives for works of art. But the kind of art history that I write is based on, on how the technical means and all the challenges that artists overcome when they make their own works. And so when when I was writing about Andrew Jimmy with it’s been an enormous amount of time learning about watercolor painting, and trying to imitate what and her wife was doing. And that really gave me huge insight as to the challenges and the problems that he had. When he said, Well, it took me 20 minutes to do this watercolor but I’m completely exhausted. I can’t do anything else was this day and I know exactly know what he’s talking about.

Eric Rhoads 9:03

So did they rotate? Let’s back up for just a second. Because I’m curious when that journey began, which came first the, the curator or the artist.

Timothy Standring 9:19

It’s, a braided narrative. I was a studio major and as an undergrad, a painter. And for some reason or other, I didn’t think it was that challenging. So I turned to art history, which was hugely challenging and difficult for me. Because writing doesn’t come naturally to me, I work so hard with it at but I’ve painted watercolors now for about 40 years, but only in the past five or six years that I really began to think seriously. And thanks to many of your efforts and the little seminars in the events that take place across the nation, those are been hugely informative for me, and and then I’ve networked in the Denver community where there’s a really great sense of camaraderie and sharing among many artists about trials and techniques. So it was studio first art history, graduate degrees, a career at the Denver Art Museum for 30 years organizing 20 exhibitions. But now I’m trying to balance back and paint more.

Eric Rhoads 10:35

So, now, there’s a reason I retired from that role. But I understand that you’re continuing to do a little consulting Is that right?

Timothy Standring 10:44

Yes, I’ve got one more exhibition, and…I wrote an essay. The exhibition is entitled Whistler to Cassatt and it opens up in Denver, November 2021, and then goes to the Virginia Museum of Art. And it’s about American artists who worked in France from around 1865 to 1913. And I wrote an essay on suck Tour, which is actually finished, or the appearance of paint on the surface. And that was an interesting concept. For artists working in the second half of the 19th century. We have people like Homer who goes over to France and so this is fine. He really didn’t. I mean, he went more as a as a tourist than anything else. But if he wanted to see his painting in a salon, but here, he’s he really wasn’t influenced either way. But there are others like akin to who had a really horrible time trying to manage colors. And along with that, I started to paint oil paint. And I discovered that that really informed my writing, because I could understand the challenges that whisper Aikens, even hopper who spent time over there, as well as America, Assad and others, how they really reacted to what was going on in terms of the salons and the Academy, as well as the independent workshops and masters. That answered your question a little bit.

Eric Rhoads 12:34

So do you think that, not to slam other curators by any by any stretch, but do you think that they can even come close to understanding what you’ve discovered by learning to paint because it’s, it seems to me, this is more of a consumer thing than it would be a curator thing, but there is this misnomer that These people, from anybody, any artist historically or any artists living, there’s this misnomer among those who don’t know, that these people just picked up a brush one day and they were magically talented. And that, we believe, as a culture that if you want to be a brain surgeon, you got to go through eight or 10 years of school, you’ve got to get all this education. You can’t just start doing brain surgery yet. We tend to think that artists just magically have this ability. Do you think that that’s something that curators believe or do they really understand the struggle though, that went through that?

Timothy Standring 13:45

I don’t think they understand the struggle. I sometimes talk about how can you write about Shakespeare’s sonnets without understanding the rules of making a solid in terms of paintings and drawings, There are so many challenges that that artists face with the technical means that they have to overcome. Maybe what’s happened is that ideation as well as iconography, and content has taken over the past couple of decades in terms of art history. So when art history is taught, it’s about subject matter. It’s really not about stylistic shifts and connoisseurship. I think there’s room for both. But I think that what’s happened is that a complete understanding of the of the technical means of making paintings and sculpture, but let’s keep it to two dimensions are enormous. And you can, you can only begin to identify with that if you’ve taken any classes. I remember. I think I For sure, but a number of art history programs that drop the studio component of graduate programs and that would have been so enlightening to many, simply because they… touching chalk to paper and how you position your hand, how much pressure you put to it, how you twist turn, is going to affect mark making and that’s going to affect the meaning that one is giving to a work of art. But yeah, I’m with you, Eric, sometimes, there are labels that are written of art history since Gaia did go on and on and on. I mean, at least I’ve had a great group of colleagues at the Denver Art Museum where we had mutual respect of understanding label writing, that an extended label should be 75 words. section labeled maybe 125 words because people won’t read anymore. And if they want to know more, they’ll go ahead and find it. But at least they’ve got the original work of artists stimulate them to further research and study on on those works of art. But it’s it’s so captivating to know how much goes into to making works of art. And the other thing that I I found amazing is how hard artists works. Work. didn’t check clothes, say, I go to work every day. It’s not just dilettantism. It’s something that’s extraordinarily taxing. And it takes a great deal of discipline, all the artists that I’ve written on. They work nine to five, seven days a week. I asked a couple of hours, what do you do on vacation and they said, we think about painting T. Allen Lawson his family says, Sorry, you’re not going to be painting on vacation. He only shows you. It’s very hard work. It is rad as Andy and was said it’s exhausting at times. But, I’ve also learned in being an art historian and I’ve written on a British watercolor landscape sketching in an exhibition catalog, glorious nature British landscape painting 1760 to 1860. And I learned that one of the reasons why British watercolor painting grew and bergeon throughout the 19th century, is because they they had popular pis picture as sketching, so their instruction manuals, there were guidebooks is to tell you where to stand for a picturesque view. There were instruction manuals with little hand colored tips of colored paper to show you, here’s how you match the color, and that inform the broader public and gave them discernment, so that they could begin to understand what the artists were doing. And except their brilliance as well as their mastering of various techniques. And, and I think that’s what, what you’re doing in the broader field of publications, as well as holding all of these various events. It informs a broader public so that we begin to collectively recognize excellencies in painting in a realistic mode, realistic vernacular. And what’s happened unfortunately, in the past couple of decades is that is that The broader let’s say, many tastemakers have misunderstood that it’s not just replicating nature it’s it actually deals with a great deal of intelligence and thought and, and the goes into making landscapes. So even though you go out and plein air paint, you still have to make artistic decisions. And those decisions are equally informed by one’s measure of how much art history you have, but also your training, your technical knowledge, and all packaged together as well as your audience because artists want to have a dialogue with visitors are going to look at their pictures and what closes the entire dialogue is actually talking about works of art that were produced by these This and their viewers…

Eric Rhoads 20:03

It appears to me that there are, the tastemakers as you refer to are oftentimes they’re so obsessed with what I would call modern art or modernism abstract, whatever the title is that they have almost looked at what we do as something that’s been done before. So it doesn’t need to be done anymore. Why do you think that is? Or do you?

Timothy Standring 20:36

Well, I mean, there are individuals writing today who are a little bit more balanced, such as Peter Saito of the of the New Yorker. I’m fascinated that he led the revival in fact, one of the revivals of Norman Rockwell and in 1974 review and said, what’s next Like, I mean, he’s as good as us. Look at look at Willem de Kooning when Sejal went out to de Kooning studio in Milan, and he turned to the turning and said this book man, Rothko. And he said Rockwell, and de Kooning took the book opened up the page, shoved it in ….face and said, Look, he’s one of us. He’s just as good as us. He’s an incredible painter. I think what’s happening is that people just aren’t looking at works of art for their own criteria of evaluation. So it’s kind of like judging a Volkswagen on a Mercedes standard. They’re both apples and oranges. They’re different. And I think if people just relax and suspend their beliefs as to what constitutes a work of art, and begins to work out, the problem solving that is involved in individual works. We’d all be better off and we’d all be able to have a collective dialogue. Whether it’s non objective painting or abstract painting or working in a realistic vernacular. I mean that there are just brilliant painters out there that are that really should be recognized on a broader scale.

Eric Rhoads 22:28

There are painters today that that are every bit as good as any painter in history who are not getting that recognition.

Timothy Standring 22:40

I know. And it’s, sad. I mean, well, let’s look at the positive. How do we change that we change it through your efforts, we change it through my efforts of getting people enthused and excited about looking and looking at the proper way and I think sharing that with colleagues in the industry in the museum industry as well as among collectors, it’s only going to work with with a with a broader public that begins to recognize what many of these artists are doing and, that’ll take some time and the tide will turn.

Eric Rhoads 23:31

It’s interesting, because you look at the newsstand, where you know a lot of consumers have an opportunity to be influenced and pick something up and and plein air magazine, at Barnes and Noble nationally is the number one selling art magazine in America. It outsells all the art and all the photography magazines. And it it has it’s a term that nobody even knows and I think it’s I think what’s happening there is it’s that beautiful image on the cover that I think people are drawn to. There’s a lot of evidence about museum shows and you know this better than anyone else that I sometimes think that museum whoever’s making determinations about what some of the museums do, I think they’re bored with the past and so they want to do something fresh and new. And yet you look at what happened to the show at the Met, the Sargent show at the Met where there were lines around the block. I think that people are still interested but I think that the again, going back to the tastemakers we’ve got to figure out how to get them interested. And I agree with the public but I wonder sometimes if they’re listening to the public.

Timothy Standring 24:51

I’m retired. I you know that there are two jobs from every museum director. across the country that are at the forefront of his or her direction, and that is one fundraising. And number two, the program. And the program of an institution, I think, is an interesting place to start, because that’s a dialogue that should take place with a broader constituency of individuals very much the way we did at the Denver Art Museum, and that is that it’s made up of about a half dozen people that meet weekly, sometimes bi weekly. And we figure out, figured out a schedule with beacon exhibitions and then going into maybe more experimental exhibitions. But there’s always that money component, ie beacon exhibition exhibitions, which would bring in many that would help pay For those other kinds of exhibitions, also, I think there needs to be a broader dialogue as to what do our broader constituencies, what would they like to see? And how would they like to have it represented? And and I think that maybe in the realm of contemporary curators, there needs to be an opening dialogue that says… doesn’t have to be cutting edge all the time. And it doesn’t have to be, blue chip modernism, that it can involve, what’s taking place elsewhere by many of these local artists, all across the country, and that could be one of the ways to increase the visibility and the consciousness of many of the artists who who paint and This realest vernacular.

Eric Rhoads 27:02

Yeah. And of course asking, people who don’t know is sometimes a problem too. Yeah, I’ll tell you a quick story is my nephew who is probably 30 to 33 years old, was with one of his internet millionaire buddies in Las Vegas, and they wandered into a photography gallery. And this guy dropped a million dollars out of beautiful photograph a million dollars. It was it hit the record books, as a matter of fact, it was in the media, first million dollar paint photograph sold or something like that. And I said to him, for a million dollars, he probably could have had a phenomenal masterwork, some something, he certainly could have had a Bouguereau or something like that. And he said, What’s that? And he said, you have to keep in mind that when I was in school, they ripped that away from us. We didn’t have any art classes. We didn’t have any art appreciation said my generation doesn’t know anything about art. He said, my friend would probably buy those paintings that you talked about. If someone would just tell him about him. He said Your job is to educate them and educate us.

Timothy Standring 28:15

Well, I think you’re doing a good job. I mean, you’ve got a brilliant editor and Peter Trippi, who you really do and, he knows how to make those articles accessible to a broader public which is is so important. But, for 30 years when I worked as a curator, I’ve worked with a number of local individuals and tried to help and help them build collections. And, you don’t tell somebody premiere a crew Bordeaux, when they only understand Thunderbird. And, and so and then at the same time, when going to art fairs. I would tell them don’t buy Baltic, by Park Place at least by utility at least by a railroad but but don’t. And so it takes a little bit of consoling and intimidation and, and persuasion and education and handholding. I mean, a number of money people are are extraordinarily bright. And they’re quick learners. And I think that’s one of the ways in which if we had a broader communal activity, in terms of curators educating the broader public instead of simply cutting edge contemporary works, or other kinds of blue chip works, don’t buy works of art as trophy collecting by works of art. So that You can learn and develop and form your own knowledge along the way as you’re, you’re building the collection. And it’s a diplomatic art, it’s not easy and not everybody has that kind of skill set either.

Eric Rhoads 30:18

So what is that process like in terms of, somebody might be listening to this, who is a collector or wannabe collector, maybe has gone to some plein air shows, and seen some artists and trying to develop an eye but, I know in my own particular case, when I was really green at this, I was drawn to things that were almost photorealistic, that the one compliment you get when you’re out painting, which is actually not a compliment for most of us is Oh, it’s just like a photograph. Right? And, how do we how do we develop these people? people so that they can develop a sense of taste and they’re not being critical of, what they’ve picked. Right? What’s your process?

Timothy Standring 31:09

Well, number one, I mean, you have to start off with a sense of passion. I mean, it doesn’t matter how much art history you give or how much information if you don’t have a passion for what you’re doing. That’s number one for working with various individuals. You want to show that this is exciting, this is fun. This is, it’s a worthwhile endeavor because it enriches all of us. And some people have money that can can buy really wonderful things, but you want to get them as enthusiastically involved as you are, and say, This is why this is important. And and begin to teach discernment. It’s very much like teaching people how to drink wine. It’s based on varietals and and you start with varietals and then you with terroir, and you deal with nationalities but and so it’s the same with with works of art, going to fairs, and say, I would advise people to get trusted individuals who, who are knowledgeable and and who are pretty much like Switzerland. They’re neutral. And they’ll give a unshared commentary about works of art, both to the sellers as well as to the buyers. You know that. The best way to do it is be honest, and not sugar and not say, Well, this is great just to make a sale. But you really want to have people begin to understand for themselves, that yes, this is going to work. in your living room, in this and our second piece is going to be something that’s going to relate to that either thematically stylistically or iconic graphically. I remember one person, I went to their home. And I walked through the whole thing. He was a new trustee and and he said, Well, what do you think? And I said, Well, this is horrible. It’s really a horrible collection. I mean, you had a designer who purchased all these pictures for your installation. And, they’re completely inappropriate for these various spaces and rooms. So he turns to the lot of us or half dozen there. And he said, Okay, we’re just going to take corporate jet to New York and go buy paintings. And I said, No, no, no, it’s not like going to Walmart. We’re going to fill up the cart. We’re just going to do this over the next couple of years. And we’re going to do it slowly and we’ll bring work To your attention that will be appropriate for these various spaces. And I’m really proud of that. And I think that individual really loves those works of art. That makes sense in the spaces and in hopefully, had learned a great deal. So that’s, I hope that answers part of the question.

Eric Rhoads 34:24

It does, but it answers part of the question, but it raises other questions and one of them is that this is a concept that most of us have not heard myself included, and that is, how do you determine that a painting is appropriate for space?

Timothy Standring 34:44

Well, two people could agree but the third person doesn’t it’s not easy. It’s not easy. You simply have to keep talking. And it’s it. Sometimes you have to reach a compromise and say, Okay, fine.

Eric Rhoads 35:16

But you’re talking about the designer saying, oh, there’s purple in it, it matches the couch.

Timothy Standring 35:23

No, no, this these are our people who actually, no, no designers. No, this is just people collecting works of art and acquiring, I should say acquiring works of art, and you’re helping them understand why it’s significant. I also…is this a work of art that the museum would want to acquire? Absolutely. And is this something that’s close to that? Yes. So And also you have to anticipate how much time and effort they want to put into the the entire event of acquiring works of art.

Eric Rhoads 36:18

How important is it that these people love what they’re buying, it seems that that should be important. Because they’re going to live with it.

Timothy Standring 36:30

Yes. And because I tell them, do not buy works of art as investment. You’re going to live with this and moreover, you want to get something that’s going to grow with you. You’ll see something different with this. You’re fortunate enough to have Monet in your in your home. And you’re lucky enough to notice how sensitive the lead that was painted on plain air and All the problems that he had solved to overcome and create this beautiful scene and it’s worked people really love their Monet’s and, and other works of art. So that’s what I, I tried to work on, show my enthusiasm and then they become curious and say, Why are you so excited about that? Why, is this making you so excited instead of that other picture? Where, let’s say, we’ve got to Monet’s we’ve got three more days. Why are you excited about this one, as against those other ones, and then you explain, just go through a whole variety of factors, but this comes from from 30 Being a curator of having a trained eye and also having experience in the field.

Eric Rhoads 38:07

Yeah. Well, that’s why having somebody like you to help is enormously important. You just raised another question in my head just thinking about that. I remember hearing the story of I think it was willdan, Stein, Weldon Steen (Dinnerstein?) in New York, the dinner, who, four or five generations, three generations ago, whatever, discovered a lot of these impressionists and a lot of the painters in Europe and just became their patron and just bought up everything that he could and filled a warehouse that would fuel a, 100 year business. And, of course, I wonder I’d love to have seen that warehouse and what was in it and I wonder if, some of what was filled up or things that never became a very valuable Have any significance if if you were given a somewhat unlimited budget today put you on the spot here and and I said Look, I want to fill up a warehouse of things that a painters today living painters today who people are going to look back on in 50 years, 100 years, maybe some of which haven’t even been discovered yet. Who would you buy? What would you buy? Maybe it’s not so much specific painters, but maybe it’s specific topics or content or styles etc.

Timothy Standring 39:49

I do have a big sense that sympathy for contemporary as well contemporary, non objective or Let’s say contemporaries against realist painting. But what would I go out and buy? I would go out and buy things that are I just have to coin it as integro. In other words there, it’s very much like analyzing a novel. You know, the lie has to be honest throughout the entire work of fiction. And as soon as that lie is betrayed as soon as the dialog falters, you stop reading and throw the book against the wall and say, I’m not going to finish that novel. And same thing for a work of art. Whether it’s, it’s realistic or not. I would look for, you know, what’s really integro in in in That artists have a corpus of works. That that really works on all six pistons. Yeah, and and that goes back to bench on forms the shape of content. I mean there’s an interaction between the final project product and and the methods that went into making it. Mark Bradley, Julian mariu, Gerhard Richter, I just love it. But I’m a little bit rusty because I’ve been I haven’t been to many fairs recently. Nobody have but yeah, But there are some…it’s hard to answer that, Eric at the moment.

Eric Rhoads 42:11

Yeah. Well, and I and and I put you on the spot a little bit too. In terms of best advice. You’ve had a lot of artists around the world who are listening to this who are part of this massive plein air movement that has kind of cropped up the last 10-15 years. I think all of us secretly, quietly probably yourself included, I don’t know, maybe we have delusions that maybe one day we’ll get discovered and one day, we’ll be in a museum. What is your best advice to any artist in terms of development of their work or development of their careers?

Timothy Standring 42:52

The advice that I give a lot of artists and mentor. Keep working. Sometimes I’ve seen artists go into networking mode, as against a working mode not I would simply say, the world will find you the world would will discover you. And there’s this urgency to have this dialogue on the part of the artists tonight. I understand that. And I recognize that, but there’s nothing that replaces hard work and discovery and problem solving from the hard work that comes into patterns. Number two, establish a network with other artists in your community. So that there’s some sense of camaraderie while you’re working with an entirely solitary existence. I mean, it’s, yeah, you’re all by yourself.

Eric Rhoads 43:58

Well, and also influence that also informs the growth because, if you’re stuck in your studio and you’re not seeing what other people are doing, you’re not going to be challenged to experiment yourself.

Timothy Standring 44:12

Right. The other thing is, is just having informal critiques with others. This visiting studios and talking about paintings and it’s, it’s really helpful to have other people articulate when they look at your painting and go, Oh, this is what’s going on or not going on. And that’s, that’s also leads to further discovery on the part of an artists and in making works of art. Then there’s that network component, which is important, but it shouldn’t dominate. And I guess just being lever about keeping that network that that really works for you as much as you can and, and learning from all of this, but, you know, your workshops that you’ve been putting together have been extremely informative, and helping the nuts and bolts of how to become an artist how to move forward. Maybe how to network with local curators and and local dealers as well as local collectors. It’s it’s all of the above, but the primary component is that that very much hard work in the studio.

Eric Rhoads 45:44

All right, excellent. So we have a few minutes left, what I’d like to do is talk a little bit about maybe a little bit of art history, some of some of your favorite artists and why they’ve become important. To you. I’m just curious about that because you have such good taste you’ve written how many books have you read?

Timothy Standring 46:08

I’ve just written a weekday heart. I’ve wrote a number of essays on Pusan. I’m finishing a catalog resume on Giovanni Benedetto Castiglioni I’ve published on Degas, Rembrandt and many others and done many exhibition reviews of my most recent reviews on Hopper, Hopper in the hotel, which was a great exhibition, which is great sign of recognition of a realist painter. The late comic, Edward, both at Richmond, Virginia Museum of Art and then moved on to Indianapolis. Great show. But what you know, I just loved Van Gogh. I loved Degas. I love Rembrandt, but an oddball out is perhaps Nicholas… Yeah. And it’s probably that I’m attracted to him because he is such a challenge. And if any artist is going to put a survey class to sleep quicker than nodos it’s going to be Nicolas… And so I think I’ve got a lifelong ambition to try to get the world excited. But this French artist…

Eric Rhoads 47:35

I got an order when I went to the there’s a beautiful little museum and on floor and I got very excited about his work. When I saw the collective especially the plein air works they had such energy.

Timothy Standring 47:51

Yeah, yeah. Isn’t this great to have this kind of discussion? This is what this is this additional advice to all those artists have a dialogue you know put your mask on stay succeed product, have a coffee with somebody else. But keep the dialogue going along with the visual dialogue participant to go hand in hand.

Eric Rhoads 48:26

Well, I’m trying very hard to do is to create this dialogue between artists you know that we have had hundreds and hundreds of artists who have become friends with others by coming to an event like the plein air convention which by the way is coming to Denver, and to be able to connect and to sit down and have lunch with and and just dialogue about art and you know, learn about what others are doing and what inspires them, what techniques have worked for them and so on and it reminds me of the cafes of France, you know that when when the Impressionists would get together at the…and dialogue, I’m sure they were arguing about things all the time. And, that’s what I really hope to have happen is, I’m trying to create a giant dinner table, where there’s a giant worldwide movement of dialogue that’s going on. And we’re now seeing, interestingly enough, it all started in Europe and then it came to America and then Europe forgot about it, and then America forgot about it. Now that we’re seeing this resurgence and now it’s starting to spread back to Europe. we’re now seeing plein air shows across Ireland in England and France and some other other locations. And it’s all because of this dialogue that’s been taking place.

Timothy Standring 49:46

Absolutely. Absolutely. Well, I would say I was timid and and went incognito to first plein air – one of – your conventions. But I loved it. I loved it. And I learned so much. So it’s a great sense of encouragement to many listeners. Don’t hesitate. You may think I don’t know how to hold on to a brush or not. That’s not important. You will learn and you’ll have a great time. On my refrigerator. I’ve got Michelangelo’s dictum, never stopped learning.

Eric Rhoads 50:25

So one last question. You mentioned you were doing a catalog resume for someone. What should I or other artists be thinking about? it? As you know, someday maybe if we’re lucky enough that somebody is going to want to do a catalog resume on us? What’s missing that you wish the artist had done?

Timothy Standring 50:51

Well, Giovanni benedito Castiglioni dates 1609 1664. He didn’t have a right Have a registrar. So I would record all the works of art, if you can, when they go out, at least keep the thumbnail image recommend Versa of the work. Read has it measurement size. You never know what’s gonna happen with your your corpus of works of art. And any other information along with that. I wish there was some kind of statement. I’d love to hear my artists voice. The only time I hear His voice is in depositions, and in legal documents from 1655 from a big trial. But and maybe some kind of chronology which is extremely helpful for people in the future to sort of understand that maybe this is how it works about David. On the directory traversal of those works of art. And catalog raising is old works by an artist and so the difficulty is that Giovanni benefitfocus to be only worked with his brother Salvatore, his son, Francesco Casta, Rene and, and so it’s about four or 500 works of art that has to be sorted out as to which ones were original which ones may have been done by collaborative method. So it’s, it’s been taking me about 44 years and, so that 95% I’ve got 5% more to finish it.

Eric Rhoads 52:41

Yeah, that’s a huge job. Well, I think that a lot of us, don’t really ever expect to be somebody who’s going to be written about but you’d be surprised and I did a thing on my noon facebook youtube daily the other day with John Pototschnik see how organized this man was he had every image every sketch in a notebook numbered, filed away and I thought, you know, somebody does a book on him and 100 years, they’re going to love discovering his archive.

Timothy Standring 53:16

Claes Oldenburg did that. I think he he numbered all of his sketchbooks. It’s really helpful. But, but it’s also when you look back, you know, you might want to go back to your sketchbooks a couple years prior to that time. And you’ll again have a self discovery. Right? Go Oh, my God, look at look at what I was doing then. I didn’t recognize it. But I do know.

Eric Rhoads 53:45

So do you show any of your work? Is there a place we can see your work?

Timothy Standring 53:53

StandringWatercolors.com and There are some works at Kitchell Fine Arts in Lincoln, Nebraska. And …up in Edward, Colorado. Excellent. And somebody told me to work on my Instagram. But there’s only so much to do.

Eric Rhoads 54:20

You’re retired now you have all the time in the world, right?

Timothy Standring 54:23

Oh, yeah. Right.

Eric Rhoads 54:28

Well, thank you. Thank you so much for doing this today. This was absolutely fantastic, very informative.

Timothy Standring 54:35

I tried to give you as much information as possible, anyway.

Eric Rhoads 54:41

Well, thanks again to Timothy Standring. And I find him fascinating. I think it’s absolutely amazing what he’s done. And you want to get some of the books that he’s done. They’re absolutely incredible. Are you guys ready for some marketing ideas?

Announcer 54:53

This is the marketing minute with Eric Rhoads, author of the number one Amazon bestseller “Make More Money Selling Your Art: Proven Techniques to Turn Your Passion Into Profit.”

Eric Rhoads 55:04

In the marketing minute I try to answer your marketing questions. I haven’t been stumped yet but I’m sure somebody will stumped me at some point I’m it’s bound to happen right? Anyway, email your questions to me [email protected]. And if you want to check out the website artmarketing.com has tons of articles I’ve written about art marketing. Here’s a question from Kathy in Indianapolis who asked Is it a good idea to list your prices on your website for your paintings or on your social media? And if so, why or why not? I’ve always wondered this because if people don’t see the price, how are they supposed to know how much it is and some artists don’t do it? Some do it. So what’s the right way? I don’t think I can say there’s a right way or wrong way. I think that the way to say it is you got to make your choices. Now I will tell you a story. A dealer friend of mine in the I’ll just say into Texas dealer friend of mine in Texas, was having this great debate about whether or not he should put prices on his website because no dealers were doing that at the time this a few years back. And I said, I think you should I would put my prices on there because the internet is all about instant gratification. And if I am in another country, or if I’m sitting up at four o’clock in the morning, I browse around, I see something I want to be able to buy it. I don’t have to pick up the phone and call you. And his argument was, yeah, but I if I get them on the phone, I can talk to them and talk them through it and help sell them. And my argument was, yeah, but you might not get them on the phone. Most people don’t want to get on the phone anymore, and some will some won’t, but you need to be able to sell it anyway. So he took a chance on it. He did an experiment and he put his prices on the website right away right away. I just felt so totally vindicated here, right so right away. He gets a An order that came in at like four o’clock in the morning, just like I said it would happen it was from some foreign country. And the order was for get this $650,000 for a big piece of sculpture. This is a top tier gallery $650,000. Now, when he arrived the next morning, he had a wire transfer for the money in his bank account. And he was able to confirm it and be able to send the sculpture and pack it up and send it to wherever it was Brazil or something, I think. And and so, from that point forward, he always put his prices on his website. Now some dealers still don’t do it. Some artists don’t do it. I you know, I think it’s debatable but I think, in this this culture, we’re going on Amazon and we’re shopping for things we want to be able to have instant gratification and I think that art is Really is the same way. And so I would do it, that’s what I think is the proper way to do it. And you also can have opportunities to upsell for framing or you know, pick a different frame or things like that. Most of the website providers provide things like that now, so I think it’s a really good idea. I, you know, again, it’s debatable, but I think it’s worth a try. And if you have a reason why it’s a bad idea, let me know, I’d like to hear it.

Eric Rhoads 58:24

Next question comes from Randy in New York City, or Randall, who says it seems that the best artists rise to the top and are working and that working on your art and getting to the highest possible level of development is the most important thing to become famous. Would you agree? Well, I think there’s a couple of things in here. First off, this sounds like a trick question. I know it’s not random but the famous you know, what’s more important? Is it more important to be famous or is it more important to be successful? Is fame successful, you can be famous and not make any money is that You want? Do you want to be famous and successful financially, you know, you got to figure out what you want. But here’s the problem. It seems like it should be the case. I mean, you would think that the universe would do that you spend your life working on your work, you get really good at it, and you put it out there, and then it just automatically gets recognized. And that happens sometimes. I mean, people do get discovered they do get recognized from the quality of their work. And clearly quality tends to rise to the top and gets the higher prices. But if you don’t put it out there, sometimes it’s not going to be seen you know, what if you don’t just get discovered what if you don’t get a gallery? What if you don’t find an agent? What if you don’t get seen? I have seen so many instances and learned about so many people throughout my career of people who are brilliant painters who have never been discovered. I had I was had an opportunity I was asked to come to England to try and talk a particular painter into getting out there and going into the market. And because he was so shy, he didn’t want to do it. And he had, it was a brilliant artist, and he wouldn’t even sell his work. And he’s in his particular case, he just didn’t want to do it. And but there have been so many instances of people who wanted to do it, but they didn’t, that, you know, they just never got anybody interested in. Um, so I think the thing is that, that selling your work is a lifetime effort. As long as you’re going to be selling your work, you’re going to have to be somewhat assertive, some would say aggressive, you have to be willing to put yourself out there. I mean, let’s say you’re at a cocktail party, and you meet an art dealer and you’re so shy that you won’t even say hey, I’m an I’m an artist, and I’d like you to look at my work. Well, first off art dealers get that so many times they may not pay attention to it, but they also might say, Yeah, I would like to look at your work but some people are social You know, marketing is sometimes just a matter of raising your hand and telling people what you’re up to. It doesn’t have to be anything beyond that. But a lot of people think marketing is something they don’t need to do. They don’t need marketing skills. They think marketing is crass, for some reason, but some have been lucky and gotten out there. Some have not. So I would say that you’ve got to be really sensitive to the idea that learning marketing is important. Let’s let’s say this, you know, I think a great thing for an artist is to eventually get a two or three great galleries, maybe more or to get a great handler, maybe somebody to work for you, maybe somebody to be your your agent. But you know, the reality is that usually you have to do some marketing and build some some awareness before somebody wants to do it. It’s like galleries want to go after successful people. They want proven people sometimes they’re not willing to take the risk and so you got to get out there. So learning and discovering marketing, go to artmarketing.com. Check it out. See if You can find some things that might be of value to you. I think you might find it to be helpful. Anyway, I think that’s, I think that’s the answer.

Announcer 1:02:08

This has been a marketing minute with Eric Rhoads. You can learn more at artmarketing.com.

Eric Rhoads 1:02:15

Alright a reminder to get registered for realism live soon it is an online conference there’s a $200 price increase at the end of September and it’s a it’s gonna be a massive conferences already 1200 people signed up so go to realismlive.com, be part of this phenomenon. You will not regret it. There’s a money back guarantee if you attend. And after the first day you just don’t think it’s worth your money. You’ll let us know we’ll send your money back we’ll cut you off you don’t have to attend the rest of the thing. And so there’s no risk and it’s going to be amazing. People have said it’s like a fire hose into a tea cup of information. That’s what they said about plein air live, realism live is going to be also incredible. It’s just a broader topic range, right? So it’s not just plein air painting its landscape. It’s still life. It’s portrait, it’s figure all the things that we all want to do mostly want to do. Anyway, if you’ve not seen my blog where I talk about art and life and other things, check it out. It’s called Sunday coffee. You can find it at coffeewithEric.com and remember fall color week is still going on and you can register at fallcolorweek.com get to paint some color. If you don’t live around the color. It’s great thing to do, and we’re going to do it live. I’m Eric Rhoads, publisher and founder of plein air magazine. Remember, it’s a big world out there. Go paint it. We’ll see you. Bye bye.

Announcer 1:03:37

This has been the Plein Air Podcast with Plein Air magazine’s Eric Rhoads. You can help spread the word about plein air painting by sharing this podcast with your friends. And you can leave a review or subscribe on iTunes. So it comes to you every week. And you can even reach Eric by email [email protected]. Be sure to pick up our free 240 plein air painting tips by some of America’s top painters. It’s free at pleinairtips.com. Tune in next week for more great interviews. Thanks for listening.

Announcer:

This has been the plein air podcast with Plein Air Magazine’s Eric Rhoads. You can help spread the word about plein air painting by sharing this podcast with your friends. And you can leave a review or subscribe on iTunes. So it comes to you every week. And you can even reach Eric by email [email protected]. Be sure to pick up our free ebook 240 plein air painting tips by some of America’s top painters. It’s free at pleinairtips.com. Tune in next week for more great interviews. Thanks for listening.

- Click here to subscribe to the free newsletter, Plein Air Today

- And click here to subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue!