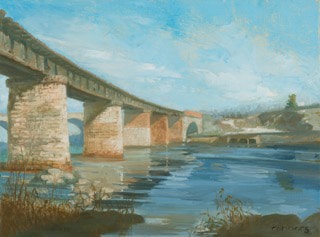

For centuries, artists have emphasized the practice of creating oil sketches as a special type of painting. The small, quickly executed works were originally made as preparatory studies for finished paintings, a practice that emerged in Italy during the 16th century. By the next century, oil sketching had spread throughout Europe, and its scope changed considerably. No longer restricted to preparatory studies, the oil sketch was used to make smaller copies of artworks, to work rapidly from nature, to reproduce imagery for pictorial analysis, to create gifts for patrons, and to work from the imagination. With its extensive studio applications, coupled with a broader range of colors, the oil sketch expanded and rivaled the traditional sketch media of stylus, chalk, and charcoal.

Artist Patrick Connors curated a show earlier this year that revealed how generations of artists used oil sketches to quickly capture gestures and to study the effects of color and form. “The Loaded Brush: The Oil Sketch and the Philadelphia School of Painting” demonstrated the depth and breadth of the legacy of oil sketching. Included were a number of rarely seen artworks from the 19th century to the present that represent diverse talents and styles depicting a variety of subject matter.

The artwork was created by alumni and faculty of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), including the historic artists Thomas Eakins, Susan Macdowell Eakins, Thomas Anshutz, Cecilia Beaux, Alice Barber Stephens, Violet Oakley, Arthur B. Carles, Faye Swengel Badura, Arthur DeCosta, Seymour Remenick, and Louis B. Sloan. Several contemporary artists also presented their oil sketches, including Elizabeth Osborne, Vincent Desiderio, Bill Scott, Stanley Bielen, Patrick Connors, and Renée Foulks.

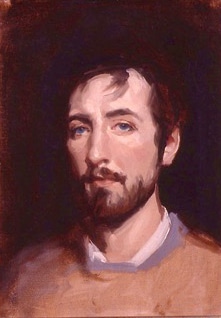

One of the most important artists associated with the PAFA was Thomas Eakins (1844–1916). He used oil sketches both in his studio practice and as a teaching tool. Three of his oil sketches included in this exhibition offered insight into the artist’s studio practice, his visual poetry, and his legacy. The three works constitute but a fraction of the many sketches Eakins created throughout his career. Their usefulness would eventually extend beyond his own studio practice to influence other 19th- and 20th-century artists, as seen in the other 26 oils.

Artists who followed Eakins were inspired by the visual poetry and potential of the practice and were motivated to follow his methods. Others reacted against the method, but grasped the intent, applying oil sketching to expressive, chromatic, or perceptive experiments.

In addition to being a critical tool for his studio practice and a catalyst for much of the work by others, Eakins’s sketches offer another disclosure: it is difficult, if not impossible, to find a group of oil sketches done in Philadelphia before his own. There is good reason for this, as it was Eakins who imported and popularized the European practice and aesthetic of the oil sketch in the city. Implications from this revelation extend to other aspects of his oil sketches, chiefly his use of pictorial structures that affirm his European training over his American instruction. In terms of scholarship and appreciation, it is of more use to understand Eakins as a French Realist rather than an American Realist, as he is more commonly recognized.

During his four years abroad, from 1866 to 1870, Eakins studied art primarily at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris under renowned master Jean-Léon Gérôme. It was in Gérôme’s private studio that Eakins was first introduced to oil sketching. Then, in other ateliers and private studies, he immersed himself in this studio practice. After his return to Philadelphia in 1870, oil sketching remained a significant part of his working routine. By 1879, so many artists had been inspired by Eakins’s example that there was an identifiable Philadelphia school of oil sketching.

Initially, the circle of inspired artists consisted mostly of Eakins’s students at the PAFA, where he started teaching in 1876: Susan Macdowell Eakins, Thomas Anshutz, Alice Barber Stephens, and Cecilia Beaux. Those four represented a new generation for whom the benefits of oil sketching would once again be discovered, incorporated into studio practice, and eventually disseminated to a receptive audience. In fact, the school, with its emphasis on preserving the artist’s first impression, would help shape the movement that would become known as the Ashcan School, a loose collective of diverse talents under the leadership of Robert Henri, a PAFA alum.

In the realm of critical appreciation, the oil sketch’s value increased with each successive wave of practitioners, critics, and connoisseurs. In 1879, when Eakins was in charge of PAFA’s curriculum, he radically departed from traditional art training for his scholars. Despite his extensive training and skill in traditional drawing methods, he discouraged drawing from antique plaster casts and even from life models. Instead, he had students paint after the casts or models. Eakins’s painting instruction, primarily through his own example and European experience, was in part derived from practice and principles inherent to the oil sketch.

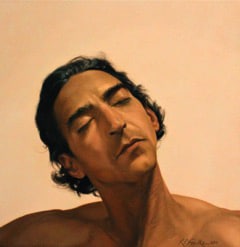

Contemporaneous art academic thinking remained largely contrary to Eakins’s own. In fact, a writer visiting PAFA in 1879 to report on art teaching methods in the United States asked Eakins, “Don’t you think a student should know how to draw before beginning to color?” Eakins replied, “I think he should know how to draw with color,” and continued, “The brush is a more powerful and rapid tool than the point or stump. Very often, practically, before the student has had time to get his broadest masses of light and shade with either of these, he has forgotten what he is after. … Still the main thing that the brush secures is the instant grasp of the grand construction of a figure. There are no lines in nature … there are only form and color.”* (*The Art Schools of Philadelphia, Scribner’s Monthly 18 (1879), 740–41.)

Eakins recognized that the oil sketch solved a critical problem for educating artists, one that was at the crux of academic training: how to turn a draftsman into an oil painter. In his Beaux-Arts training, Eakins used the oil sketch as a means to master finished oil painting, a training he would eventually pass on to his students. Unlike similarly trained artists, he did not abandon the practice; in fact, it became a lifelong interest in which he quickly realized and revealed his visual poetry. Many of his oil sketches are preliminary studies for more finished works, but this should not mislead the viewer to think that the sketches are dependent on other work for their worth. Eakins’s sketches, along with the other exhibition sketches, disclose the painter’s thoughts — a valuable insight into a private and often unseen art.

Eakins, if there was a criticism it would be that he has no ‘color’, no complements. The painting ‘Archbishop Diomede Falconio’ and the two sketches for ‘The Negro Boy Dancing’ as well as the Biglin Brothers Racing, all at the NGA, are testament to this. An Eakins work on paper: ‘Poleman in the Ma’sh’, wash over graphite and black chalk, 1984.3.9, in their collection, has as much life.