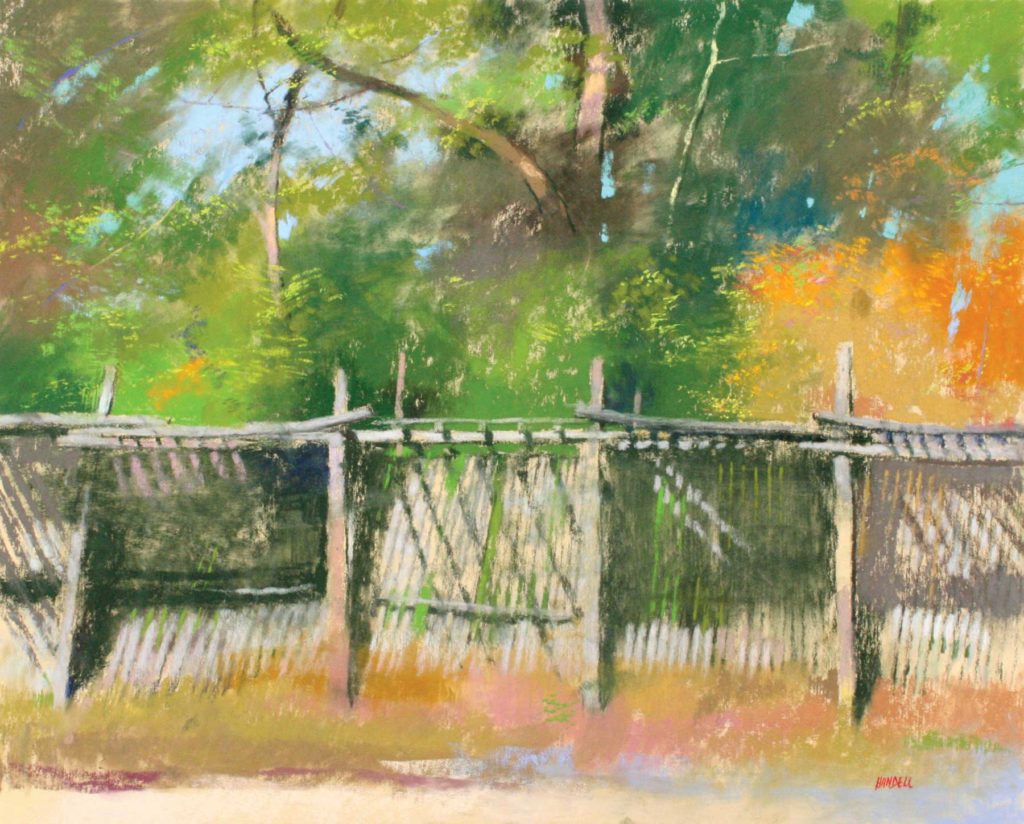

New Mexico artist Albert Handell uses pastels to respond both to the specifics of what he observes and to his emotional response to the locations. He says, “I will eventually frame the painting, not the location I observe, so the image has to be more than an exact replica of the landscape.”

Albert Handell compares painting to dancing. “I’ve been swing dancing for many years, and when I have a partner who is inexperienced, she usually stumbles around trying to remember all the steps she learned,” he explains. “I show her the basic rock step and encourage her to just feel the beat of the music and trust that she will know how to move her feet. In many ways, painting is a similar kind of experience. It’s important to know the basics, but if you think about all the techniques you learned and don’t let yourself respond emotionally and physically to the subject, you’ll stumble around the picture.”

The point of Handell’s analogy is that while technique is important, it needs to be at the service of expression. “If I’m captivated by a fallen tree, I become obsessed with trying to respond to what I see and want to know about it,” he says. “But once I’ve done justice to that subject, I am free to create a space around it that celebrates but doesn’t distract attention from the center of interest. The peripheral areas of the painting can be gestured, suggestive, or specific. That all depends on what the painting tells me it needs.”

Handell continues, “This metamorphosis takes place when I am painting. I begin by focusing in on one area of the landscape and paint it close to completion. Then the light changes, and the shapes, shadows, and rhythms evolve. As the scene changes, I hold on to the memory of what first inspired me, but I also consider the new options that have been revealed to me. If I am successful in conveying my feelings about that central image, then the painting becomes a personal expression, not an objective report.

“Rhythm has become very important to me as an artist. A stationary tree or a moving stream turns and twists and gives evidence of an inner life. Those repetitive patterns are often subtle rather than dramatic. I capture the moments in time that suggest change.”

Related > Albert Handell has a NEW Streamline Premium Art Video on how to paint landscapes in oil!

Although Handell has traveled all over the world, painting and teaching, he prefers to work near his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico. “I seldom drive more than 20 minutes away from my studio,” he says, “and I take sheets of Kitty Wallis paper or U-Art art papers, 500 or 600 grade, mounted on museum rag board — up to size 16 x 20 — sticks of pastel broken to about one half or one third their original size, with the numbered label left in the studio; and at times some watercolor paints to lay in an underpainting when I am working in mixed media. I often return to favorite painting locations, but even when I’m exploring a new area, I don’t spend more than five minutes looking around for a subject to paint that’s better. I have found that searching around for the perfect spot wastes time and leads to indecision.”

Describing his initial painting steps, Handell says, “I apply a light application of pastel describing the local colors, then I gently wipe the surface down so the pastel floats over the paper. My concern then is about the placement and proportion of the shapes on the toned surface, and about painting from dark values to light ones.

“I also use strong cast shadows to frame the focal point of the picture, and softer shadows to suggest the distant shapes. I continue working for about three hours on location and bring the painting to a satisfying resolution. I then take photographs of what I’ve been painting and of the surrounding areas. Those photographs can be useful in the studio for creating larger oil paintings of related subjects.”

During the winter months, Handell prefers to work in his studio on larger oil paintings. He usually takes a break after 90 minutes of painting and leaves the studio to answer phone calls, check e-mail messages, and do other chores so he can return to the studio refreshed, with a clear vision. “I will spend most of one entire day taking a painting through its initial stages of development,” he says. “Then I put it away and will start another painting the next day. That way, when I return to the first painting, I can see it more objectively and know what specific adjustments need to be made.”

Related articles:

PleinAir Art Podcast with Eric Rhoads Episode 6: Albert Handell

Spotlight on Albert Handell

Lovely article, thanks!

[…] Suggest Responses to Nature” by Steve Doherty featured in the Plein Air Magazine, and also on http://www.outdoorpainter.com […]