Utah artist Steven Lee Adams is very clear about why he bought the three paintings discussed below. They contain passages or suggest processes that he admires and likes to see in his own work. And one of them represents a new approach for the seasoned painter.

“I’m constantly shooting for something in my own work, and when I see it even just obliquely in another work, it definitely excites me,” says Adams. “When I was young, museums mesmerized me for hours; I loved everything. Now I find it really hard to get excited by other people’s work for the most part, unless it hits some of these notes that excite me. When I see ground that doesn’t seem to be trod over, hashed and rehashed, that has life in it, then it excites me.”

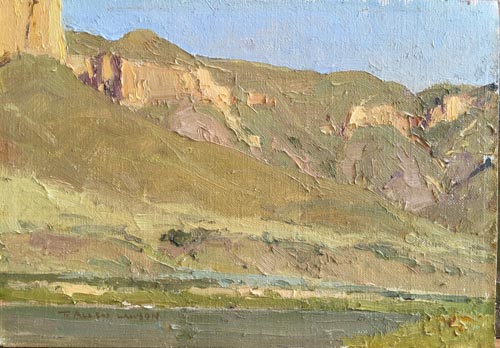

“Near Mudspring Coulée,” by T. Allen Lawson, 2003, oil, 7 x 10 in.

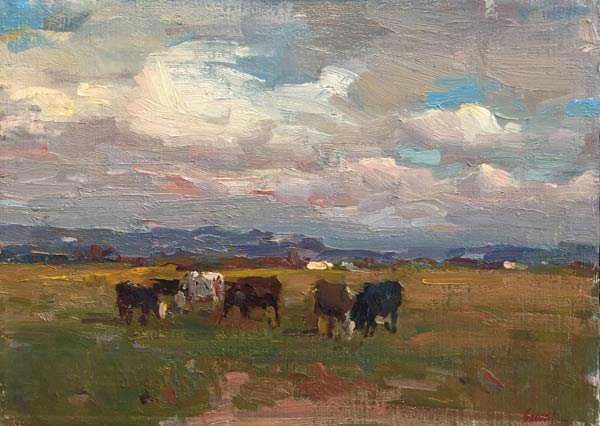

First up is an untitled piece by Galust Berberian. “Galust and his brother Ovanes came over from Russia to study with Sergei Bogart in the ’70s and ’80s,” says Adams. “They both live in Idaho, which reminded them of their home. Ovanes is very flamboyant, and his work shows that. It’s very immediate work. His brother Galust, I admire more. This piece by him is really elegant and thoughtful. It captures an essence of a place without forcing, without dictating. I’m not sure if it is plein air, but it has the feel of a plein air piece.”

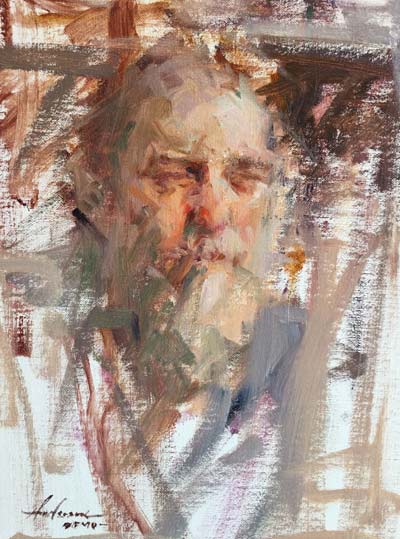

“Out West Art Show Demo,” by Carolyn Anderson, 2015, oil, 16 x 12 in.

Next up is a piece by T. Allen Lawson, one that fans of that artist may be familiar with, as it appeared in one of his books. “It was one of last ones he had available from the book,” says Adams. “It’s a little guy, and it’s really subtle, and it’s an amazing example of how subtle plein air can be when you don’t take everything literally. Some elements may be literal, but they are subjugated for the overall feel of the landscape, which is really hard to do. You get too committed to what you are seeing. He simplifies it, taking out whatever doesn’t serve the painting. If you start jamming everything you see in there because it’s there, because it’s reality, you ruin a painting. But his piece is so simple and subtle — this may be why it didn’t sell earlier. But that’s what I’m drawn to. It isn’t as obvious, and I feel like there’s genius in that.”

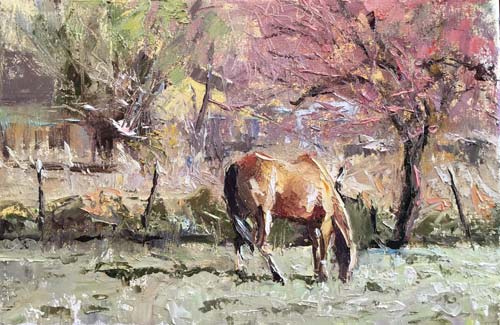

“Untitled,” by Steven Lee Adams, 2015, oil, 8 x 12 in. An example of Adams working through concepts learned from Carolyn Anderson

The last piece was a bit pricey, but Adams couldn’t help himself. “Trades are great, but the pieces I purchase are the ones I can’t live without,” he explains. “I try to hard to stop myself from spending a lot of money on paintings, but occasionally they just get you.

“I bought Carolyn Anderson’s demo from the Charlie Russell show [the C.M. Russell Museum annual benefit auction and show, held in March]. She’s been one of my favorite artists for a long time. I had never met her. I was sitting there in the gallery and somebody said, ‘Hey, Carolyn Anderson is doing a demo out in the commons!’ Everyone jumped up and went to watch her. I wound up buying the piece she was working on and subsequently signed up for a workshop with her.”

“West Desert Storm,” by Steven Lee Adams, oil, 16 x 24 in. An earlier piece from Adams

Much of the appeal of the Anderson piece is that Adams is branching out into figure painting, and he notes that Anderson approaches painting in a very different way. “Her whole approach is very different than mine, and different from the way most people teach,” says Adams. “Everyone is taught to get these shapes down — the shape of the head, the shape of the jaw, and build these forms — circles, squares, and triangles. It’s not that she disregards those shapes, she just doesn’t build with those shapes. She works from a point and measures the distance from there to landmarks. She’ll measure the distance from the dark point on an eyebrow, to the mouth, or ear, and keeps those measurements accurate. It eliminates the tendency to create a crayon drawing and to fill in what has been drawn. There’s a sense of it being grounded; it’s very accurate, but also very fluid. The figure breathes within the space around it. That’s just an amazing shift for me. I’m really excited about.”

In fact, Adams has already started painting with that approach. That Anderson demo may prove to be a crucial addition to his collection.