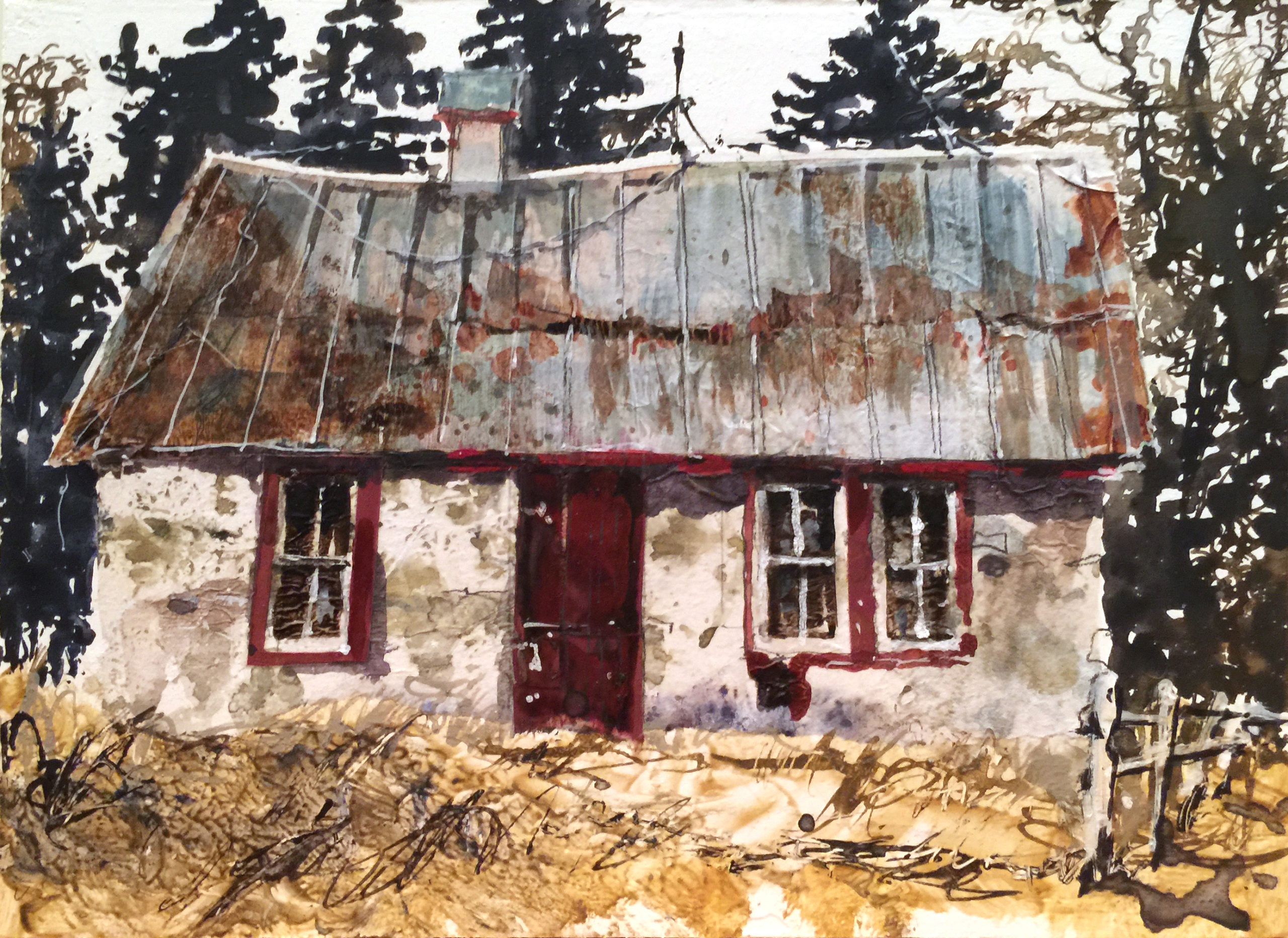

Elements of wear and tear in Mat Barber Kennedy’s textural watercolors show signs of life and how we live it.

Better With Time

By Stephanie Laufersweiler

English artist Mat Barber Kennedy knows that worn and weathered subjects tell the best stories. He’s been drawn to the aging, decaying parts of buildings for as long as he can remember. “I think the life of a city, of a culture, of a family or a business, is revealed in the ways that our structures age,” he says. For nearly 30 years he’s channeled his appreciation for the used nature of what he sees into art. “In some sense I think my work is a kind of portraiture hoping to reveal more than just the appearance of things, but revealing something of the life of things,” he says.

The Art in Adaptability

An architect’s son, Kennedy began to shift toward fine art while studying architecture at the University of Sheffield and then at the Royal College of Art in London. “I started to explore my ideas about architecture through paint, collage, and mixed media,” he says. While other students concerned themselves with how they could protect the pristine quality of what they designed, Kennedy was excited at the thought of how occupants and the passage of time might affect and change the structures. “To me it was all about how people adapt,” he says. “We renovate, repair damage, and redecorate. The passing of the seasons and the touching of a door handle by a hundred dirty hands reveal the patterns of use and decay that mirror our own lives in some way.”

The heart of a place exists not in its grand landmarks, Kennedy says, but in the everyday details we experience even if we don’t pay them particular attention. “I love the Eiffel Tower, but it’s not the essence of what it feels like to be in Paris and to experience Parisian life,” he says. “That is found in the mansard roofs, the spaces between the windows, the communal entrances to apartment buildings, the bus stops, the building numbers, the folding chairs, and the newsstands. It’s those things that I want to celebrate in my work, hopefully revealing their dignity and importance through the energy of my composition and mark-making.”

His wife, Sherry, gave him his first set of watercolors and nudged him to “get out and paint something” one afternoon in London in 1991. “My first plein air paintings were typically of chimney stacks, shop signs, front doors, and windows,” Kennedy says. His parents were also avid art collectors, and growing up in a home that cherished art made becoming a professional artist feel within reach. “I was fortunate to be mentored by Colin Kent, John Blockley, and Leo McDowell, and was elected to join their ranks in the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours very early in my career,” he says.

In 1995, he moved with his wife and children to Chicago, where he teaches watercolor at the American Academy of Art. He also leads illustration classes there from time to time and is developing a new course on the business of being an artist.

Working Loose, Then Precise

Kennedy has never considered himself a purist. “I’m always experimenting in the studio,” he says. “My work is unmistakably watercolor, but I’ve spent years trying to escape the flatness of the page by adding non-watersoluble elements, thickening agents, and collage, applying paint straight from the tube with my fingers and palette knives, and rubbing it away with shirt sleeves and paper towels.”

He even sprinkled handfuls of dirt into his first washes for some historic museum pieces he made recently at the Olmsted Plein Air Invitational in Atlanta. “It created texture and brought authenticity of place,” Kennedy says. “There are lots of things that I try in the studio that fail, but every success gets added to my tool belt and expands my vocabulary.”

Building texture the way Kennedy does requires long periods of drying time, which often allow him to produce two paintings at once. “Usually there is an attention to surface detail that just takes layering and more layering and cannot be rushed,” he says. “The attention to detail in the context of a loose and vibrant overall image is one of the things that I think people can recognize in my work.”

He builds the major masses quickly, but then areas of focus and precise detail require a slow and sequential building of layers and specifics.

“The looseness keeps the painting from becoming clinical,” Kennedy says. “The tightness lends the painting an exactness and specificity that can only come from careful observation.”

Reflections of Who We Are

His on-location approach has evolved from primarily research-gathering for studio paintings into making finished art on site. Kennedy realizes his methods put him on the slow end of the spectrum compared to fellow plein air painters in the United States, but he avoids “looking sideways” to stay true to his vision. “I try to learn lessons from my colleagues, both technical and philosophical,” he says, “but I’m getting a lot better at understanding how to remain focused and confident in what I’m trying to see, capture, and express in the frenetic heat of a plein air event.”

“I very much consider my work with tools and buildings to be about who we are,” Kennedy says. “The scars on the handle of a hammer are such a direct reflection of the work that its owner has done, the care with which it was kept, the hurry in which it was stored, the times that it was misused. There are stories behind a scratched initial, a splash of paint, a darkening of the wood, a fraying of the grain.

There is a quiet dignity and a distinct personality in humble tools, barns, doorposts, and window frames, that I hope to capture as a testament to the lives of the men and women who owned them.”

Visit EricRhoads.com to find out all the amazing opportunities for artists through Streamline Publishing, including:

– Online art conferences such as Plein Air Live

– New video workshops for artists

– Incredible art retreats

– Educational and fun art conventions, and much more.

> Subscribe to Plein Air Today, a free newsletter for artists

> Subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue