The coast of Maine, with its turbulent surf and craggy shoreline hugging a brooding and dark North Atlantic Ocean, promotes clarity in thought and vision. Into this environment came an American impressionist painter known for painting atmosphere. The results, as presented in a current top-notch show and catalog, are stunning.

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) studied in France, had much success as an illustrator, and began to branch out into his own style of impressionism, bolstered by the efforts of other Americans whose work he saw in expositions. In 1889, he wrote, “The American Section … has convinced me forever of the capability of Americans to claim a school. Inness, Whistler, Sargent and plenty of Americans just as well able to cope in their own chosen line with anything done over here. .. An artist should paint his own time and treat nature as he feels it, not repeat the same stupidities of his predecessors …The men who have made success today are the men who have got out of the rut.”

Hassam moved back to New York City and had success applying his impressionistic approach to urban scenes, but in summer, he once again traveled, and one of his favorite spots remained Appledore, an island off the coast of Maine near the New Hampshire border. A poet named Celia Thaxter had created something of a salon scene on the rustic island, and Hassam found a favored landing spot at her home and at the large hotel on the half-mile isle. At first, he concentrated on Thaxter’s beautiful gardens and the scenes close to the hotel, but he eventually ventured afield, especially after Thaxter passed away in 1894. His body of work on Appledore constitutes about 10 percent of Hassam’s lifetime output, and this collection has been thoroughly explored through the book American Impressionist: Childe Hassam and the Isles of Shoals and an exhibition of the same name on view at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, through November 6.

“Moonlight,” by Childe Hassam, 1892, oil, 18 1/2 x 22 1/2 in. Private collection

The book and show examine not just the paintings Hassam produced on Appledore, but also the geology of the area, the historical context, and much information that a modern plein air painter would find interesting regarding Hassam’s compositional choices, chosen vantage points, materials used, and other decisions regarding time of day and painting approach. In other words, American Impressionist: Childe Hassam and the Isles of Shoals is a book that will engage those who geek out on the details of Hassam’s plein air adventures.

“Poppies, Isles of Shoals,” by Childe Hassam, 1891, oil, 19 3/4 x 24 in.

Collection of National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

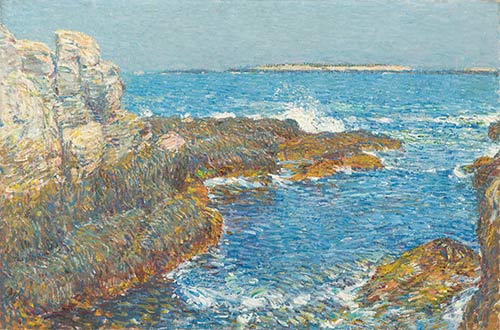

Austen Barron Bailly writes in the introduction, “Appledore’s geology and the surrounding oceanic forces remain relatively constant. The island’s consistent physical realities enabled this volume’s authors to corroborate Hassam’s painting sites—and map them. What [Hal] Weeks calls ‘diagnostic rocks’—easily identifiable markers that have not moved, eroded, or broken—can be identified in the paintings, as can the intertidal zones of particular interest to marine scientists. The authors and curators could determine how the artist adjusted his position in relation to these rocks or pools as he observed, reframed, or manipulated the views, variety, and pattern of his rugged and watery surroundings. Appledore became Hassam’s escape and his artistic laboratory, the one place he could always go to experiment and test his own aesthetic responses to composition, texture, and color seen up close or from a distance—red poppy petals; sharp, speckled-gray granite; sandpaperlike black basalt; mustard-yellow lichen blooming over rocks; glossy dark green seaweed sloshing in the waves; iridescent jellyfish; or the sun glinting off whitecaps that sparkle like sequins thrown across the surface of a cobalt-blue sea.”

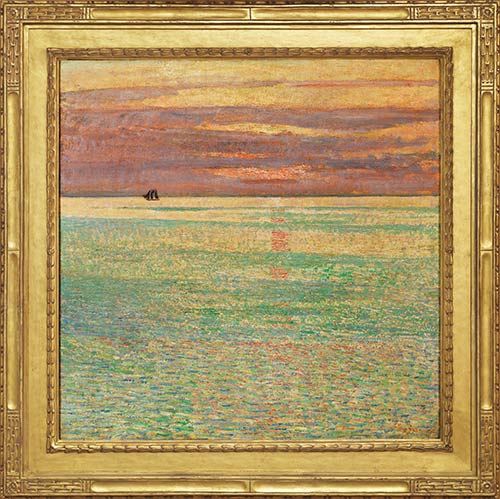

“Sunset at Sea,” by Childe Hassam, 1911, oil, 34 3/4 x 34 3/4 in. Private collection

Appledore held a certain cachet among Americans who could enjoy leisure in the summertime, enough of a cachet to explain Hassam’s willingness to venture beyond the comforts of the hotel and Thaxter’s cottage. The authors of the catalog explain that some of Hassam’s painting sites undoubtedly exposed him to biting insects, strong winds, and unrelenting sun — the kind of places plein air artists go and find themselves alone. Even his more comfortable vantage points were largely devoid of human presence.

“Isles of Shoals,” by Childe Hassam, 1907, oil, 19 1/2 x 29 1/2 in.

Collection of North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, North Carolina

“Surely Hassam, a genuine celebrity at the hotel, would have attracted onlookers as he worked away at a canvas,” write John W. Coffey and Hal Weeks in the show catalog. “However, the playful, curious, and probably annoying guests rarely figure in Hassam’s painting. His behavior was perhaps similar to a camera with a long exposure time: anything moving blurs or registers not at all. In most of Hassam’s paintings of Appledore, tourist activity, ever in motion, fails to register on the canvas. Instead, he presented a wilderness, a world apart.”

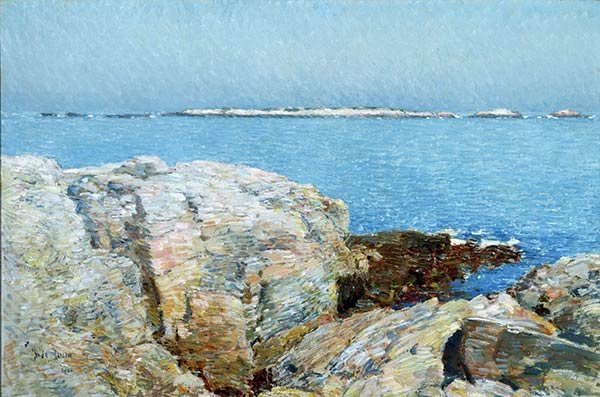

“Sylph’s Rock, Appledore,” by Childe Hassam, 1907, oil, 25 x 30 in.

Collection of Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts

In Kathleen M. Burnside’s essay in the catalog, she quotes a letter Hassam wrote from Appledore, in which he says, “The rocks and the sea are the few things that do not change and they are wonderfully beautiful—more so than ever!” Subtracting the human element allowed Hassam to include a sense of that timelessness.

“Morning, Isles of Shoals,” by Childe Hassam, 1890, oil, 16 1/4 x 22 1/4 in.

Collection of North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, North Carolina

Toward the end of the catalog for American Impressionist: Childe Hassam and the Isles of Shoals the authors offer two maps showing where Hassam painted each featured painting, and which direction he faced. Elsewhere, they discuss his painting approach, including his attention to lichen and algae, the sun-bleached and the moonlit blue. “The trio of Sylph’s Rock paintings testifies to the artist’s patient scrutiny of the visual and geological complexity of the northeast shore area,” write Coffey and Weeks. “He calibrated his painting technique—especially the dense strokes and jots of thick color—to approximate the granular textures of the rocks…. Hassam allowed himself greater liberties when it came to color. Seeking perhaps an amplified experience of Appledore, he would sometimes take the natural hues in a scene and simply turn up the volume…. In his paintings, Hassam cribbed these localized colors and applied them more generally, gilding the rocks to set off the turquoise of the sea.”

The later pieces Hassam painted on Appledore approach abstraction. Sunsets became bands of color, thick with paint. “Most of the Isles of Shoals Group are included in the present exhibition and have not been seen together in such number since their presentation in 1915,” writes Burnside. “Their striking use of color and remarkable sense of patterning and composition take Hassam’s landscape subjects to a new, more abstract level—one of ‘sincere simplicity,’ as then noted by [art critic Royal] Cortissoz.” Hassam is generally considered an impressionist, and he would question not the label, but its meaning. “The word ‘impressionism’ as applied to art has been abused, and the general acceptance of the term has become perverted,” Hassam wrote. “It really means the only truth, because it means going straight to nature for inspiration, and not allowing tradition to dictate to your brush … the true impressionism is realism.”

American Impressionist: Childe Hassam and the Isles of Shoals will be on view at the Peabody Essex Museum through November 6, and the catalog is available here.