Plein air landscapes are fun to paint, but how does one paint the pieces so they disappear into one expressive feeling of the landscape? This New York State oil painter, a figure drawing instructor at New York City’s famed Art Students League, works to go beyond pictorial reportage of the landscape and express something more.

John A. Varriano is a representational painter. His grasp of human anatomy is at a level where the Art Students League of New York has secured him to teach figure drawing. But depicting what is in front of him no longer satisfies Varriano. He seeks more.

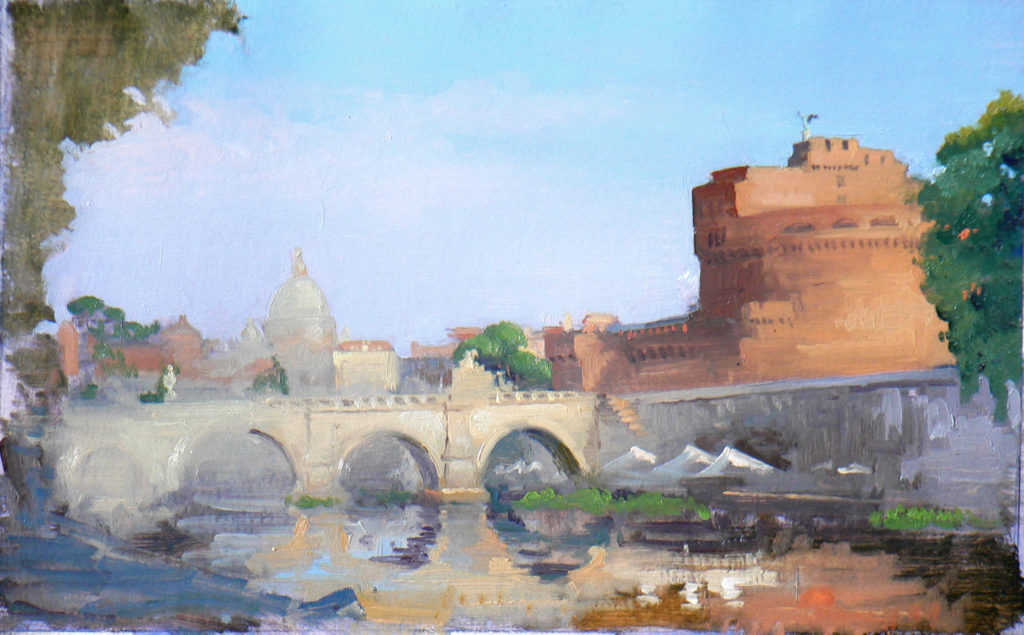

“That’s the biggest challenge of all,” says Varriano. “How do you go from reporting, to expressing, to creating something that transcends the thing that you are painting? One way is to focus on how the light washes over the entire landscape. Plein air landscapes are fun to paint, but how does one paint the pieces so they disappear into one expressive feeling of the landscape? Through the depiction of light.

“That is one of the reasons why painters like the early or late light of the day. During those times, there are more sweeping masses of light and shadow that allow you to create these progressions through the landscape, so the artist can give the feeling of walking into the scene. There’s a difference between seeing the truth of a thing and feeling the truth of a thing. That’s the difference between reportage and art that transcends fact.”

One of Varriano’s favorite ways to go further in his art is to poetically express the play of light on human flesh. “I do a lot of portrait and figurative work, and it is probably my first love,” says the artist. “It is what attracted me to being an artist in the beginning. I did a lot of figure drawing before starting into painting, and that is what I still teach at the League. So I am compelled by the idea of painting a human being first, of capturing the spirit of a human.

“I work very hard to capture the spirit of the sitter in portraits, getting a feel, a sense of the life force that is present in the model. I work pretty hard at trying to capture the essence of the gesture and the psychology that a particular pose conveys. A gesture may be contemplative, vigorous, or confident. That is what is compelling to me. But the flesh is a whole other thing. Flesh features complex relationships of opaque and transparent passages, alternating between warm and cool, and then warm and then cool again. Portraying that complexity gives a figure painting that vibration.”

Varriano continues, “And when you take a figure outside, it heightens that experience. You see these different passages in the flesh very vividly. You can have more fun and kick up the cerulean blue, add the reflected light.”

It should come as no surprise that one of Varriano’s biggest heroes is Joaquín Sorolla, the 19th-century Spanish painter known for his depictions of bathers and fishermen at the shore. “I’ve recently been very interested in Sorolla, Anders Zorn, and John Singer Sargent — but mostly, Sorolla,” he says. “Sorolla’s command of sunlight on flesh is very compelling to me. The other two had command of this as well, of course, but Sorolla’s expression of this is an expression of Spain. You see the warmth of the sand and beach reflected in the flesh of the bathers. You see in Sorolla the brilliant highlights that represent the wetness on the flesh. But in order for these wet highlights to work, the surrounding flesh has to be middle values to show that.

“It’s about opposing forces — to get highlights to work on flesh, you need to pitch the rest of the flesh lower. You must suggest sunlight, but you can’t pitch the shadows too dark. They are still in bright light.”

You may think that someone so intent on the quality of light would have strong feelings about the light in Italy, or Provence, or Maine. Varriano can speak about this, but for him, it’s not the quality of light as it is affected by latitude or altitude. It is about the quality of light as it is affected by its environment. The manganese blue of Northern Atlantic water, the warm sand of Sorolla’s Spain, the tropical greens of the Caribbean — these are the tones Varriano is expressing in his paintings.

Painting Figures in the Landscape

Varriano places figures in the landscape for many of his finished paintings. He says there are two tiers for this. The first is a landscape that includes a figure or a small group of figures as points of human interest and for scale, “in the same way you might put in the steeple of a church, or a cottage, or a horse in the landscape.”

The second approach, in which the figure dominates the composition, or the landscape and figure are equal partners, is more complicated. When the figure is more prominent, it’s an opportunity to more fully and subtly explore the quality of light at the specific location.

“Sorolla expresses Spain, and Zorn’s paintings have more of a sense of Sweden, of Scandinavia,” asserts Varriano. “I love that. I love the idea of a figure in the landscape also portraying what makes the scene specific to that part of the world. Yes, there’s an intensity of the sun in Key West, and even in Indonesia, that has a different quality than sunlight in New York. But the basic problems, I consider the same. If the sun is out, the sun is out. The difference is more about the surroundings.

“In Key West, you see the green blues in the water that infuse and reflect into everything. Sunlit, sunburned flesh has that same richness in New York as elsewhere. So much of the painting is the matter of reflected light on the figure — in particular, the ambient light reflected in the shadows. There’s a richness of the tones. Thus, the artist must work so the flesh tones don’t get washed out. On the beach, you get brilliant cool planes from sky, greens from the surrounding trees if there are any, and warm tones coming into the flesh from the sand. That is really the point.”

There’s no faking it, or it shows. “You look at some paintings by neoclassical painters, and the bathers by the stream, or the dancing nymphs, look discordant, pasted into the landscape,” Varriano says. “You can tell the figures were painted in the studio.”

The artist loves painting the figure in the landscape so much, he asked his daughters to pose outdoors for a Father’s Day gift. He and his wife, painter Marsha Massih, make a point of visiting Split Rock, a swimming hole in the Mohonk Preserve near New Paltz, New York. There they find willing — or perhaps unwitting — models.

Related > Spotlight on Figurative Artist Marsha Massih

“When I worked on one of my recent Split Rock paintings, I worked very hard to concentrate on depicting the light hitting the bathers, and yet detailing the figures enough so they didn’t just disappear into the landscape,” says the artist. “Sometimes Marsha and I will take a model down to a stream and paint a pose. There’s a nudist swimming spot downstream from Split Rock, and that offers a good opportunity to paint the figure in the landscape.”

Varriano also enjoys painting a regular landscape, and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot is one of his guiding lights. He name-checks Claude Lorraine, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Cézanne, quoting the latter’s pronouncement that painting is mostly the relationship between adjacent tones.

“I’m a formalist in that regard,” he says. “It’s the play of one little color note next to another that excites me. It’s creating a tapestry that moves across the canvas. I start always with a basic understanding of the major value masses and their relative color temperature. Then I break it down into the three simplest statements — sky plane, ground plane, and all the uprights. Then I’ll consider a fourth element — anything angled. Your landscape should read as at least three solid statements. Then you break that up into pieces.

“But the ground should all be washed in one zone, a value range that you respect throughout the painting process. Actually, that is true for all three planes. In general, the goal is to maintain your masses, but then modulate within the major masses. That’s where the fun is, the close modeling. Every major mass has at least a bit of red, yellow, and blue in it; every mass has an element of the primaries to varying degrees.”

Varriano, a dedicated draftsman, will be the first to agree that color isn’t imperative. “Claude had limited means of portraying the sunlit scene in his drawings,” says the artist. “He didn’t have the power of color to convey this. But he did have a conception of the landscape that was grand, that was bigger than the landscape he was facing. How do you convey overall creation as opposed to that one scene of a beach? The greatest seascapes do that. A Homer seascape gives you a feeling of awe. That’s when painting starts to transcend the simple depiction of something. That’s when it becomes art.”

The painter is dedicated to plein air work, but he feels that these outdoor pieces are studies. Varriano believes in learning a scene, in honing abilities, in doing the homework — then painting freely and expressively, in an effort to transcend the subject. He sees precedents for this in art history.

“The Japanese painters didn’t paint from life. They sat in front of the mountains or trees, studying them, immersing themselves in it, then went into the studio and tried to paint it or draw it,” says Varriano. “If they didn’t succeed, if it didn’t satisfy them, they went back and did it again.

“Painters used to do a lot more memory work. When you take thousands of hours of working from life, combined with a cultivated memory and the ability to visualize a scene, you can paint from imagination. Whistler and Turner worked from memory. I suspect those late Corots were done the same way — there doesn’t seem to be a particular place that matches what he portrayed. If you immerse yourself in the landscape your entire life, then it manifests itself in your paintings.”

Related > Learn how to paint like Sorolla with this new art video workshop from Thomas Jefferson Kitts on “Painting the Color of Light.”

Be to be able to give inside self-criticism and celebrate your uniqueness.

But, you can define risk parameters by using stops a different methods like hedging.

I am given many models of failure, on the.