Faced with an abundance of visual stimuli and a world of opportunity on the canvas while plein air painting, New Mexico artist Peggy Immel stays true to her vision by identifying the story of her art at the start.

Peggy’s Plein Air Painting Muse

By Robert K. Carsten

“I’ve always loved painting,” says Peggy Immel. Beginning in oils, she later switched to acrylics, appreciating their transparent quality. “I was using a grisaille method, glazing colors over grays, partly because I didn’t know how to mix colors then.”

In the 1980s, Immel took a watercolor class, where she first experienced plein air painting. “I loved both watercolor and painting in nature and did that for many years,” she says. “But when we moved to Taos in 2002, I wanted to go back to oils. I took a couple of workshops to relearn how to handle them and now I’m hooked. I used to travel the United States and Europe to rock and ice climb, but I don’t do that much anymore. Instead, plein air painting allows me to follow my muse – nature. The scenery here is so beautiful and inspiring.”

Invoking Her Muse

“I believe it’s most important to discern what a painting is about – to know what it is I want to convey,” says Immel. “Is it the light, something about the subject matter, a color combination, or color temperature gradation? Maybe it’s just a feeling I have. Whatever it is, I need to define it early on because once I know and lock that in my mind, I keep revisiting that idea as I’m working, and this gives my painting process clear direction. Otherwise, the painting can be like that story that goes around a big circle and when it gets back to the beginning, it’s not at all the same story. We have an idea, then lose it and go off following another trail, and another. Staying focused and true to the original idea is key.”

To discover her main point of interest, Immel begins by designing three small notans, using an Ebony pencil. “I make myself compose the value pattern of the picture differently in each notan,” she says. “I might try the design in three different keys – low, middle, and high. It’s 15 minutes well spent.” She also makes written notes about what attracts her to a scene, sometimes even writing a haiku.

Once she’s finalized her idea, she may create a small, detailed value sketch from the selected notan. She then marks each of the four intersection points that correspond to the golden section on the canvas and proceeds by loosely brushing in the main forms of her subject.

“I usually try to place my focal point on one of those intersections and maybe a secondary area of interest on another one,” she says. “The thing is, though, this can get very predictable. Sometimes paintings are more exciting when you break a rule a little bit. I have no qualms about moving things around, emphasizing a light or dark, or shifting a color to highlight something. I’ll even play with the location of my center of interest.”

Artistic Concerns While Plein Air Painting

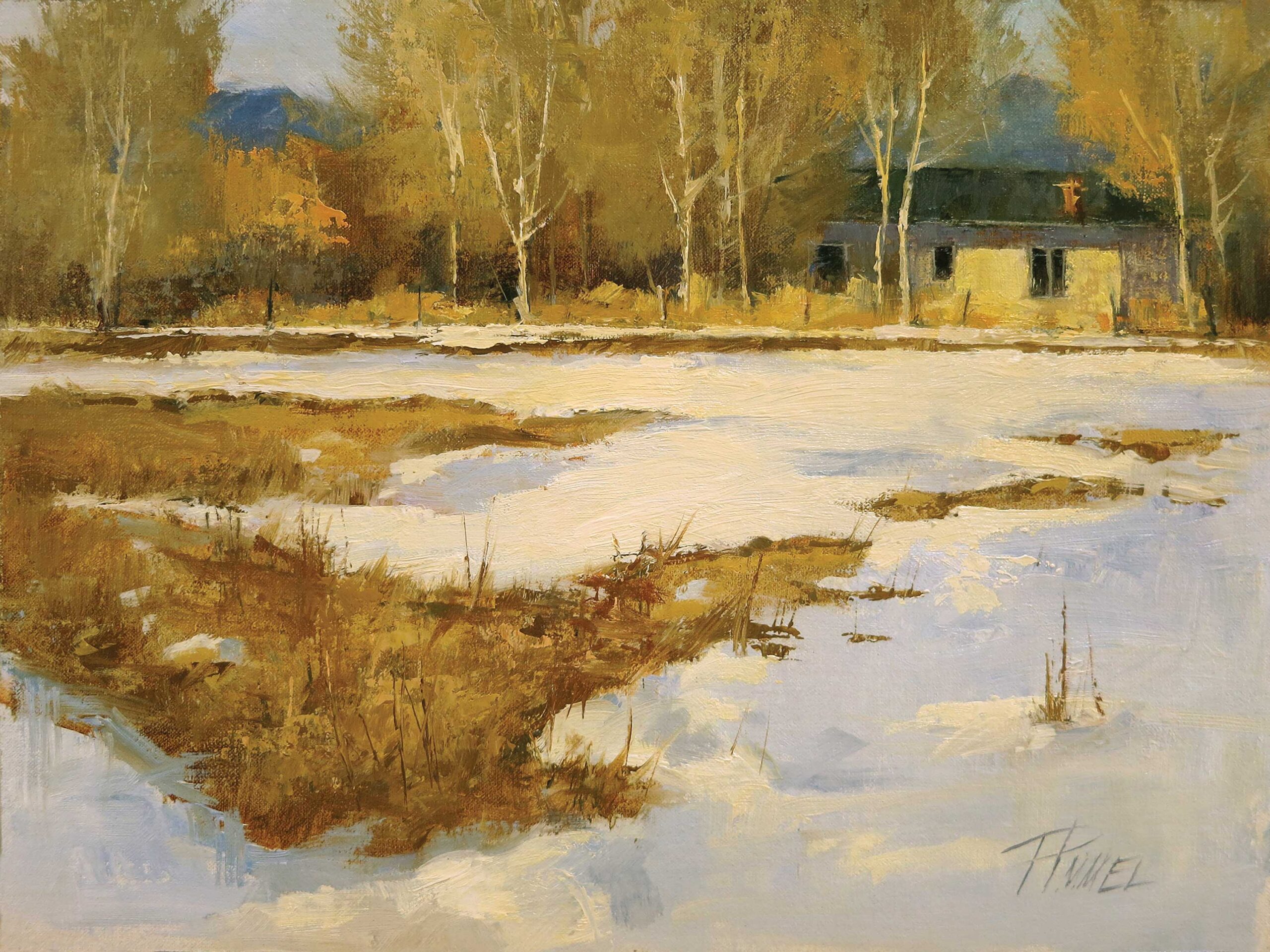

“Winter Field” splendidly utilizes an alternate placement of the center of interest. “I stood in my front yard and painted the little house across a field of melting snow,” says Immel. “I planned the pattern of the snow, working out the use of diagonals and plotting ways to keep the eye from racing off the edges of the canvas.”

To move her center of interest a little further up and to the right of a golden intersection point, she pushed the yellow of the sunlit adobe against the dark windows and adjacent lit trunks. “I didn’t make the sunlit part brighter than it was as much as I made it warmer,” she says. “I think that color temperature is one of the most underrated opportunities artists have. It’s a great way to keep value patterns cohesive. If you just change the color temperature, it can do so much, like on that little house.”

Color temperature plays a significant role in “Breezing Up at the Hacienda.” It was painted on location at Taos’s historic Martinez Hacienda, and Immel used cadmium orange to accentuate the adobe color, which complements the blue of the sky.

”Although it may seem minor, I became intensely focused on the cast shadows of the canales – the drain spouts on Southwestern adobe buildings,” the artist recalls. “I was thinking about how color temperature changes within the body of a shadow. It was cooler in the darkest part against and near the beam and warmer as it moved away, picking up more ambient light. As a painter, that’s the kind of thing that really interests me.”

Natural Beauty

A subject in which Immel creates a special kind of painterly magic is wildflowers. Of the enchanting “Fireweed,” she says, “Sometimes there’s just one of those paintings that really works, and this was one. It was a natural – the red of the fireweed against the green. I first created an underpainting of variegated greens and browns and then painted over it with opaque, lighter greens. Often, I’ll put thick paint on with a Richeson Che Son 806 offset painting knife, then brush into it.”

A Pearl of Wisdom

Undoubtedly, Immel’s impressive success in painting and teaching comes from decades of hard work. Perhaps what has facilitated this is her dedicated commitment to lifelong learning. She views every painting as a new challenge and an opportunity to improve.

“I think we learn better if we’re not trying to do too many things at once. We all have some things we’re not very good at. It could be drawing or composition, color values, or edges. Think about the thing that’s most difficult, the technical thing that you’re struggling with the most,” advises Immel, “then try to develop some drills or exercises and focus on that for some time, perhaps a year.

“It’s important to get critiques on your improvement, maybe by another painter, spouse, or teacher, because it’s difficult to see progress when we’re working on something we don’t do well. Recognizing patterns – the big and small value shapes so important in designing compositions – was always difficult for me. Several years ago I started the practice of making notans before every painting – and what a difference that’s made!”