From the Editor’s Note, Plein Air Magazine, April/May 2021

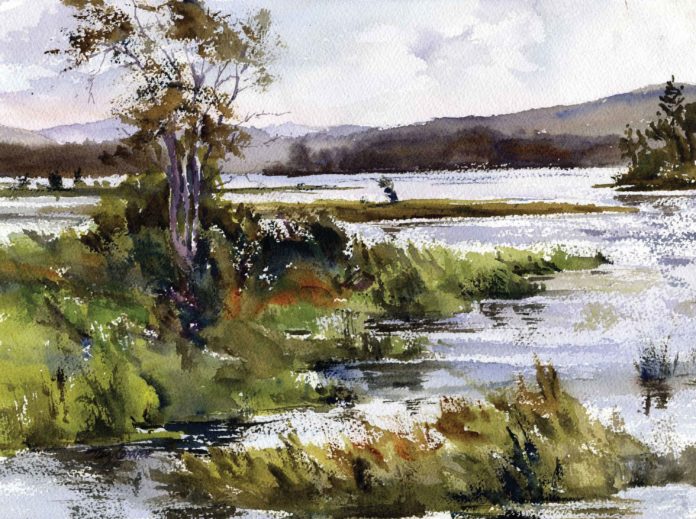

Once considered the lowest of all genres by France’s Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, landscape painting took on new life in the early 19th century. It was then that French artists, and others across Europe, returned home from pilgrimages to Italy — widely accepted as the center of the art world since the Renaissance — laden with pieces inspired by the Italian approach. The sketching campaigns embarked upon by these artists aligned with the Enlightenment ideal of observing reality firsthand and objectively gathering empirical data.

Over the following decades, artists continued the practice of sketching and painting outdoors in innumerable ways, from creating studies of specific elements of the landscape and natural phenomena to completing works of all sizes on site, sometimes returning to a scene many times to finish. In continued celebration of our 10th anniversary, we follow one timeline that reveals how we got to this moment.

From Plein Air Magazine: A Timeline

1800

Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes published his influential treatise on landscape painting, Reflections and Advice to a Student on Painting, Particularly on Landscape. In it, he developed the concept of landscape portraiture by which the artist paints directly onto canvas in situ within the landscape.

According to Valenciennes, the best practice involved making quick studies that captured the local tone, beginning with the sky and progressing down to the foreground, ensuring all parts were in accord. Details were to be ignored and no more than two hours spent on a study — or just half an hour if the subject was a more rapidly changing phenomenon, such as sunrise or sunset.

Although he was sympathetic to those who painted a scene for a couple of hours and then returned at the same time the next day to continue where they left off, he demeaned artists who spent a whole day painting a single view and then called the resulting works études d’après Nature [nature studies]. “These are just mistakes and lies against Nature,” he wrote.

1830s to 1870s

Before the 19th century, landscape painting primarily served as the basis for allegorical and narrative themes. While the French painters of the Barbizon School retained much of the formality of the Neoclassical style in their work, their plein air sketches marked a move for artists to escape the confines of the studio and to fully experience nature, to look and feel, rather than copy and analyze, then to take those studies of atmosphere and perspective back into the studio to use as reference for larger works.

Notable artists: Theodore Rousseau, Constant Troyon, and Charles-François Daubigny

1840s to 1850s

Portrait painter John Goffe Rand invented the paint tube, replacing pig bladders and glass syringes. Paints could now be produced in bulk and sold in tin tubes with a cap. The cap could be screwed back on and the paints preserved for future use, providing flexibility and efficiency for painting outdoors. The invention also meant artists could have a variety of colors on hand, allowing them to make spontaneous color choices on site. The invention of a lightweight, portable box easel a decade later also made it much easier for artists to set up and paint outdoors.

1860s to 1880s

The French Impressionists rejected the closed system of the academies, embracing modern life as a theme. Seeking to capture the effects of atmosphere “in the moment,” they based their art on the science of color and light, painting most of their work outdoors in a few hours’ time. For larger works, they would return to the same location, at the same time of day, and complete the painting. Through direct observation, the Impressionists were able to truthfully express the idea of a moment and used intense, bright colors to convey the outdoor experience.

Notable artists: Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Camille Pissarro

1870s to 1920s

A blend of academic training and Impressionist thought, American Impressionism is recognizable by its more spontaneous brushwork and a lighter palette than the work of the Hudson River School (1825 to 1870; see “Destination Inspiration: In the Footsteps of the Hudson River School” in this issue for more on this group).

Notable artists: Theodore Robinson, Childe Hassam, and Mary Cassatt

1920s to 2000s

Early 20th-century outdoor painters had a unique opportunity to work in whatever style they felt best reflected their personal aesthetic and approach, including Carl Rungius and California Impressionists such as Edgar Payne, William Wendt, Guy Rose, and Marion Wachtel. Building on the past, contemporary painters have discovered outdoor painting in droves, and many new plein air events and festivals have launched to engage with local communities.

Plein Air Magazine, 2011 to 2021

Plein Air Magazine relaunched in 2011 after a five-year hiatus (it was first published from 2004 to 2006) to encourage and support the art of outdoor painting, and to promote its advantages to artists and collectors alike.

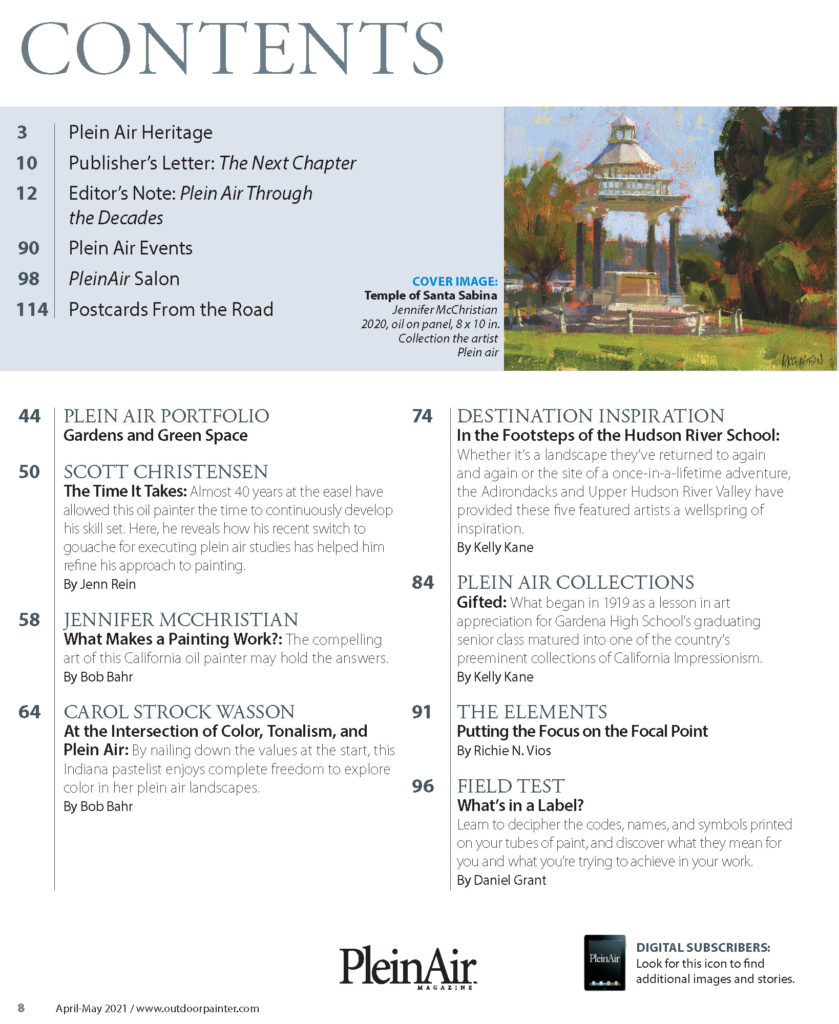

Plein Air Magazine, April/May 2021 Table of Contents:

Get your copy of the newest issue of Plein Air Magazine — available on newsstands — or subscribe here so you never miss an issue.

Related Article > Plein Air Painting Is the Largest Movement in Art History … and Growing