In the last of this series of articles, Utah artist J. Brad Holt talks about what artists are seeing as they look at the landscape, and wraps up his 22-installment body of writing. Holt studied geology in college and is attentive to what the rocks suggest in the scenes he paints.

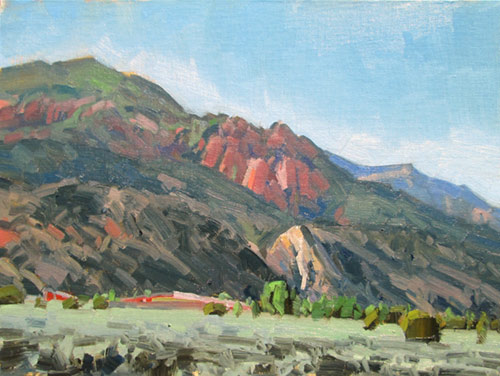

Lead Image: “Cedar Canyon — August II,” by J. Brad Holt, 2015, oil, 12 x 16 in. Studio piece

This is the final article in this series on art and geology. As I look back, I am surprised to realize that the series has run for 22 installments. I seem to have covered most of the material one would expect to find in the syllabus of a typical undergrad physical geology course. I suppose that is to be expected. We all seem to cover the basics in a similar fashion.

The entire series may be somewhat long on geology and short on art, but this is illustrative of a point that I made at the beginning: Artists, especially plein air artists, don’t really need to know anything of the science behind their subjects. It is enough to observe, and to create an artifact based on that observation. In fact, plein air painters must at times suppress much of what they know about a subject in a scholastic sense in order to simply paint the physical appearance they glimpse in a moment of time. Thus, on its surface, plein air painting is a construct of sentiment, aimed at preserving a moment when the physical beauty of a time and a place pierced the heart of the intelligent observer.

In this case, the resulting artifact is relatively straightforward, and free of deeper subtext. But the very fact that it is art implies a deeper meaning. This is easy to see in the case of conceptual art, which is almost always a product of the studio. It might also be why conceptual art is almost unconsciously placed on a higher intellectual plane from that of mere landscape painting. I would like to suggest that a subtle sense of subtext begins to enter the work of experienced plein air painters, as they delicately tweak various aspects of the plastic elements of design beyond what they are actually witnessing.

Like any landscape painter, I tend to glow with pleasure when a bystander remarks that my painting is more beautiful than the actual scene. Rather than simply recording the scene, I superimposed something of my knowledge and feelings into the piece. This is the point where plein air painting rises to the level of art. It is also the point at which a deeper understanding of the science of geology becomes a thing of great worth to the landscape painter.

All of us who paint the landscape develop an ability to mimic the patterns of nature. We understand on an instinctual level how the dendritic drainage patterns present in a hundred square feet of clay soil can have an echoed similarity to the drainage patterns of a hundred square miles of mountainous terrain. These are fractal patterns, in which patterns of great complexity can be produced through the iteration of relatively simple algorithms. If we are told that a particular crinkly line drawing represents a section of seacoast, we would be unable to discern whether it is a mile long, or a thousand miles, unless we are given a scale.

This is the nature of fractals, and it is the language of the natural world. Our innate instinct to mimic such patterns allows us to realistically simplify our landscape paintings. It also allows us to look beyond surface randomness to apprehend underlying order. It is a thing of equal worth to artists and geologists alike. A good sense of the shapes of how things grow, and how rocks erode, enables the thoughtful artist to manipulate the proportion and positioning of order and chaos within the picture plane, as another element of design.

The experienced plein air painter seems almost subconsciously to encourage those aspects of the scene that fall within the ratio of 1:1.6, and to minimize those that violate this golden mean. Alternatively, a blatant disregard for the ratio might be used to introduce an element of tension to the work, or even to make a statement about the breaking of boundaries. In either case, such manipulations would be well served by a sound understanding of the geological and biological realities of the subject.

All of the plastic elements of design may be manipulated to hone the aesthetic appeal of a particular scene. Value, color, texture, and shape may be emphasized or subdued, according to position within the composition, to heighten the impact of a design. To do so within the constraints of a recognizable landscape is a great challenge: Few pursuits are as simultaneously rewarding and frustrating as plein air painting.

It is this combination of carrot and stick that drives us to the field again and again. For we recognize in nature certain combinations of color, value, and form that are enormously satisfying to the human soul. We love certain aspects of geology, biology, and meteorology, simply because we find them beautiful. The great insight of the abstract expressionists was that this appeal could be found in pure abstract design arrangements. But I think that there is something just as profound about finding, and manipulating them, within a representational framework.

Therefore, if rocks be your subject, then learn all that you can about rocks. Knowledge is the light that allows you to ply the tools of your trade. It isn’t that I think that being a geologist makes you a better artist, or that being an artist can make you a better geologist. I think that being both make you a better human being. They are two sides of the same coin of curiosity and love for the natural world. We become good at the things that we practice, and if we practice a keen observation of nature, then we will be edified in both professions. If a subject is worth painting, then it is also worth understanding. I definitely believe that the attitude and intent of a painter is visible in their brushstrokes. Our hearts are visible in the calligraphy of our marks upon the picture plane. In this way our knowledge and love for the physical world imbues our work with a power that viewers respond to.

I would like to thank the staff of PleinAir magazine, especially Bob Bahr, who assigned me this project and has been my editor. Special thanks to Anne Weiler-Brown, my ad rep, who is always in my corner and is my biggest cheerleader. Finally, I would like to thank you, the audience, for going on this journey with me. Happy painting!