A new, award-winning book explores the relationship between artists and the beauty found in our national parks. This is a book that works to explain why painters and sculptors feel drawn to nature.

Susan Hallsten McGarry collaborated with Jean Stern and Terry Lawson Dunn for Art of the National Parks: Historic Connections — Contemporary Interpretations, an award-winning book.

The book, Art of the National Parks: Historic Connections — Contemporary Interpretations, was written by Susan Hallsten McGarry, Jean Stern, and Terry Lawson Dunn, and it earned an Independent Publisher Book Award (IPPY), tying for first place in the Fine Art category with Hopper Drawings, by the Whitney Museum. That’s not bad company, and an examination of some of the essays and images in shows why the tome is garnering such attention.

“Morning Rhythm,” by Joseph Paquet, oil, 12 x 16 in.

McGarry interviewed some of the brightest lights in plein air painting today, including Joseph McGurl, Ron Rencher, Kathleen Dunphy, Curt Walters, Kim Lordier, Kenn Backhaus, Clyde Aspevig, David Santillanes, John Cogan, Skip Whitcomb, and Scott Christensen. She says her research and her conversations with artists made it clear that just as artists were instrumental in the establishment of national parks and designated wilderness areas, the parks have given back to the artists over the decades. It is a symbiotic relationship. “Paintings helped make the parks a reality,” says McGarry. “Then from that point on we have artists using the parks. They are inspired by nature, but it runs much deeper than that. They have become emissaries for preserving nature by preserving moments in nature.”

“The Sun at Low Tide,” by Joseph McGurl, oil, 9 x 12 in.

McGarry let the artists talk in her text for the book, and sometimes the things they shared were personal. “I’ve always felt that I understand nature better than I understand people,” Kathleen Dunphy states at one point. “And I’ve never felt closer to God than watching fall leaves drop like gold coins onto Acadia’s carriage roads, or wandering along the ocean path from Sand Beach to Otter Cove. At those times I experience an awe that makes my heart beat faster. I hope my paintings convey that joy and reverence.”

“Frozen Lake,” by Skip Whitcomb, oil, 10 x 14 in.

Others talk about the urgency and forcefulness of nature in the execution of plein air painting. “There is an honesty that comes through when I’m forced into an up-tempo mode, like catching the final rays of sunlight or finishing a painting before a storm forces me to stop,” Ron Rencher says. “In those moments I tap into a deeper oneness with nature.”

“Summit Sunrise,” by Kathleen Dunphy, oil, 12 x 16 in.

The book also explores the relationship between outdoor work and studio work. For many, plein air painting is research. Studio painting is mental work. “In the studio I interpret ideas, tapping into something deeper,” states Clyde Aspevig. The gamut is here, from those who find the spiritual in nature to those who merely value the changing light of the sun on forms. McGarry, an officer for the Plein-Air Painters of America, says the book could be used by artists not just as an art book, but as a resource.

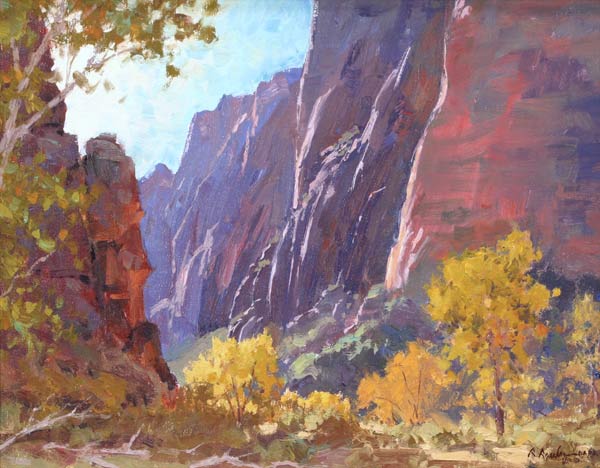

“Morning Sun Lighting on the Great White Throne,” by Kenn Backhaus, oil, 11 x 14 in.

“Plein air painters can go through this book and find locations,” she says. “A handful of the artists in the book are purely imaginative, but for the most part the paintings are site-specific. In effect it is a guide to some of the most spectacular locations, and a sourcebook on ways to interpret certain visuals and certain landmarks.”