Joseph McGurl is a champion of a technique known as sight-size drawing, an approach that can yield very accurate drawing and can also be a considerable aid to composing a painting. Here’s how he does it.

Contemporary Luminist Joseph McGurl on the Sight-Size Method

BY JOHN A. PARKS

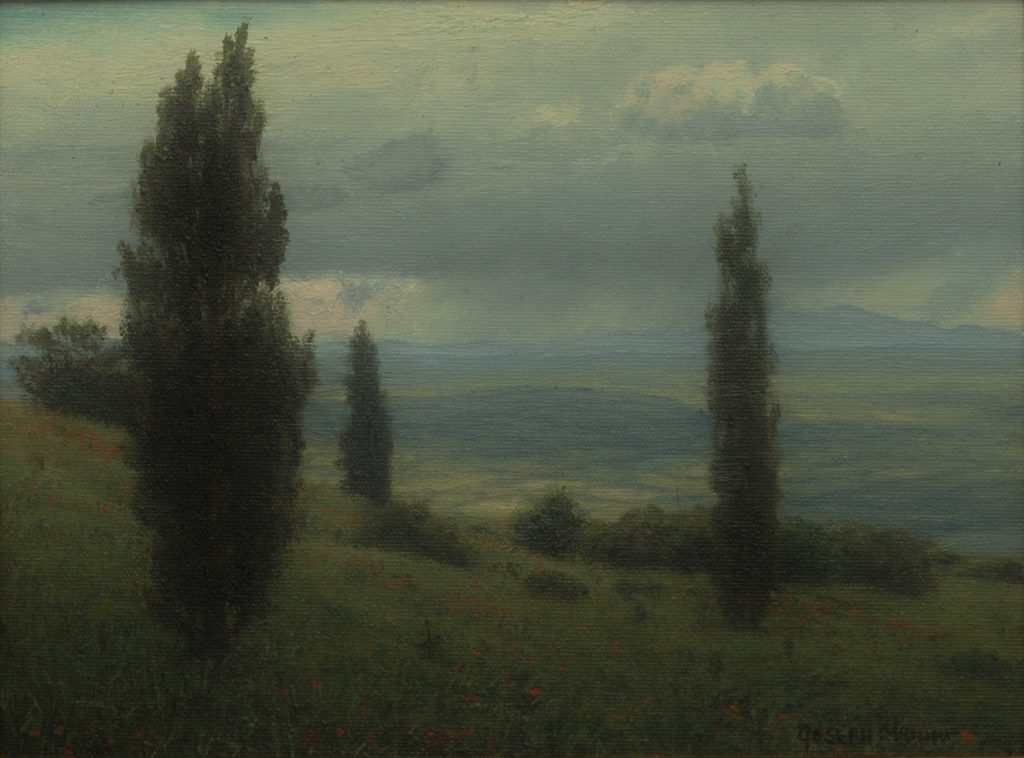

For Joseph McGurl, painting is far more than a technical exercise or even a pleasurable day out; it’s a voyage of discovery. But he’s not only investigating what’s in front of him, he’s delving into a deeper exploration of how reality works and what it means to be in the world. He styles himself a “contemporary luminist,” after the 19th-century Luminist painters who were influenced by the transcendentalist views of writers like Emerson and Thoreau. They believed that there is a spiritual component to nature that is accessible to everybody.

“Luminism was more of a philosophy than a style,” McGurl explains. “In fact, the word ‘Luminism’ was adopted by 20th-century art historians to describe a group of 19th-century painters that included Fitz Hugh Lane, Martin Johnson Heade, Sanford Gifford, and John R. Kensett.” McGurl points out that while these historic painters opted for a very smooth and quiet paint surface, he himself deploys much more energetic handling and a generally cooler palette. What they share is a fascination with how light is infused into every corner of a landscape, and an intimation that it is a spiritual force.

Renouncing Photo Reference

McGurl’s search for a deep connection to nature has led him to the decision not to use photography as reference. “I’m interested in painting the world, not a photograph of the world,” he says. “For me, the magic of art is taking a multi-dimensional experience and translating it into two dimensions. If you use a photograph, then the camera has already done that for you, and all you can do is take the two-dimensional image and make another version of it. That is very boring to me. The excitement of painting is recreating the experience, even if you are making things up based on the experience. That’s where the fun is.”

McGurl points out that not using photography can make the learning curve seem a little steeper for beginning painters, since they will have to sort out the complexities of drawing from life rather than having so much of that work done for them. But he believes the payoff in the end is immense as the artist starts to understand and master the visual world in which he or she moves.

“The other day,” he recalls, “I was painting a shoreline with a lot of kelp. I couldn’t really determine if the kelp was brown or yellow, so I rowed out and took a close look at it and saw that some of it is brown, while the younger shoots are yellow. So when I went back to paint it, I could make more sense of the color because I now had an intimate knowledge of the subject. It’s the kind of connection you can’t make if you are just looking at a photograph.”

Drawing with the Sight-Size Method

While McGurl eschews photography, he is a champion of a technique known as sight-size drawing, an approach that can yield very accurate drawing and can also be a considerable aid to composing a painting.

The idea is simple:

- The artist places his canvas right next to the subject, so there is little head-turning to shift from the view of the canvas to the subject.

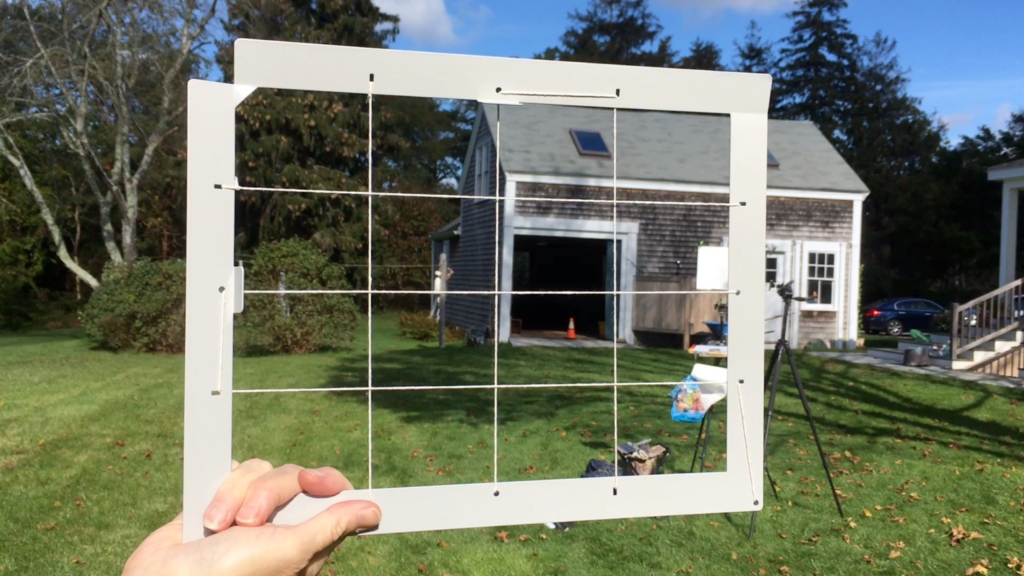

- He then places an open frame of the same size as the painting right next to his canvas. Generally the frame has a wire or string grid dividing up the space.

- An identically sized grid is drawn on the surface of the canvas.

- The artist looks at the subject through the open frame and, by stepping forward and backward, chooses whether to work with a wide angle or a tighter view.

- The closer he steps to the frame, the more of the subject he sees and the more wide-angle the view will be.

- Having decided on a composition, he must now mark the spot on the ground where he is standing so he can always return to it to check his drawing.

McGurl recommends that the artist also make a couple of marks on the edge of the frame corresponding to where elements in the composition meet that edge. This allows him to get back into position more easily.

Sight-Size Method in Action

VIEWFINDER: To find a pleasing composition, McGurl views his subject through a 9 x 12-inch viewfinder, which is the same size as his painting surface. The string grid divides the space and makes it easier to draw the shapes on his canvas.

ACRYLIC DRAWING: The artist lines up his canvas with the viewfinder and uses umber acrylic paint to sketch out the scene and make a mono-chromatic underpainting. When the acrylic base is dry, he begins to paint over it with oils.

FINISHED PAINTING: He places the completed painting in front of his subject to show how it matches up with the rest of the scene. “The colors and shadows will change with the moving sun,” he says, “but if the artist is careful, the painting should blend into the environment.”

“The subject can now be drawn exactly the same size as you see it,” says McGurl. “And this immediately makes the drawing more accurate. The shapes in your view are the same size as the shapes on your canvas, so you can compare shape to shape rather than saying subconsciously, ‘This shape is 30 percent smaller.’ It’s much easier to see errors; in fact, they jump right out.”

He points out that when the drawing is accurate, other aspects of the painting tend to be more accurate, too. It’s easier to get the right values of color and tone when the proportional relationships are accurate. “And it’s fast,” he says. “Instead of fussing with the drawing, you can get on with the painting.”

McGurl also notes that the sight-size technique helps avoid some common pitfalls. “One of the big problems we have with painting is that when we look at something, subconsciously it always looks bigger,” he says. “If there are mountains in the background, for example, we tend to make them bigger, and this screws up the proportions. In fact, we almost always see the center of interest in a painting as much larger than it should be. Using the viewfinder frame is a really good check.”

LEAVING ROOM FOR CREATIVITY

While using a frame makes for more accurate drawing, McGurl says his own use of it allows for some creative interpretation. “It lets me decide what’s in my composition and what’s outside,” he says. “But sometimes I’ll pull something into the picture that was outside the frame. The difference is that this is now a conscious decision, not the result of sloppy drawing. I pick and choose what I want to keep and what I want to change.”

One of the exciting features of this technique is that as the painting nears completion, the artist can stand back and see if it melds into the landscape. Being “sight-sized,” it should all but disappear into the view. This is also a moment when any errors in value or color will become immediately evident.

Painting en Plein Air

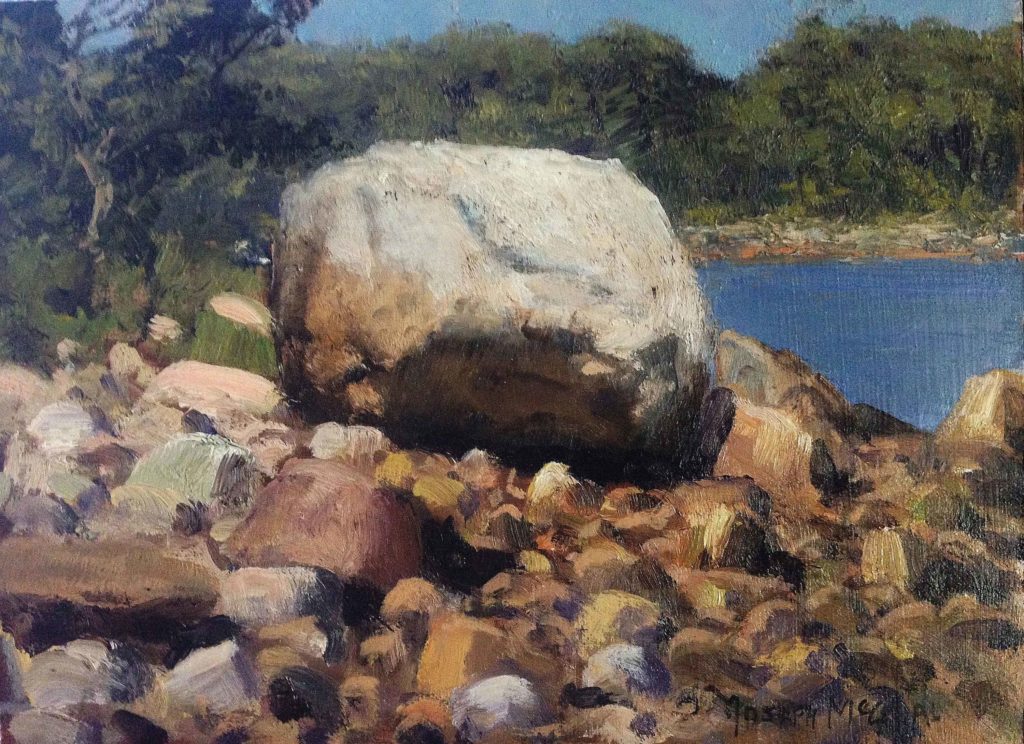

For McGurl, the process of painting often involves work done en plein air and then a later picture in the studio that develops themes and ideas from his outdoor work. The whole adventure begins with a search for a subject. “Usually I’m simply looking for something interesting,” he says.

“At this point I’m not looking for composition, but something that fascinates me. It could be some unusual rocks or a manmade structure. Then I’ll walk around it and see if I can find something that works compositionally. I also look for light and shadow shapes, or perhaps an emotional connection to the subject — some massive and dark element, a sense of solitude, or maybe a windy day on the ocean. A lot of times the composition is lousy, but the information I’m getting from the subject is so good that I want it. When I get it home I can recompose it. I don’t make too many changes in the field because I’m there to see what’s there. I want to understand nature. I’m dissecting it and reassembling it, understanding how it works. The composition is secondary. Often, though, the outdoor paintings work out and I consider them works of art. Sometimes they are just studies.”

While the sight-size viewfinder helps with the drawing, McGurl’s approach to building a painting is also designed to home in on an accurate vision of what is in front of him. “The first thing I’ll do is draw it in with umber or black acrylic paint,” he says. “Once I get the drawing accurate, I do a monochrome underpainting. This does two things: firstly, it’s easy to make changes since I don’t have to mix color. Secondly, it lets me see what the composition is going to look like. If the composition is awkward, I have the opportunity to change it. This acrylic underpainting is fairly thin so it can dry while I’m setting up everything else, then I can begin work in oil on top of it.”

McGurl doesn’t premix a palette but begins working broadly, mixing color on the fly. “I generally start fairly messy and loose and not too accurate,” he says. “I don’t want to worry about finishing things, because if I do, I’ll be less receptive to change. I want my drawing to be fairly accurate, but I’m not too worried about edges or even color. I’ll try to get it about 80 percent right, but you don’t really know what a color will look like until you put another color next to it.”

Building the painting with broad strokes and approximated color allows the artist to develop his composition quickly, while leaving room for changes and adjustments. He quotes Sargent: “Start with a broom and end with a needle.” McGurl also tends to work from background to foreground. “With landscape, it’s successive layering toward the viewer. I get everything covered fairly quickly with the first pass, and then with the second pass refine things more and make the color more accurate. In the last pass, I’ll be worrying about color, edges, and texture details.” Generally, he completes a painting in three or four passes.

As he approaches the end of his painting, McGurl uses a number of different tools to work up the various textures of his subject. “I have lot of different implements to work the paint,” he says. “I’ll take a nylon brush and give it a bad haircut so it’s really ragged. This does a really good job of making the organic shapes that you find in nature, rather than trying to paint them with a flat or a filbert. It seems crazy to paint an organic shape with a geometric paint brush.” McGurl will turn his ragged brush, using different sides to make slightly different kinds of marks. “I also use paint shapers and I have a pastry brush that I use in the studio, as well as a fan brush with a ragged edge. And then I use a palette knife a lot.”

Developing Ideas in the Studio

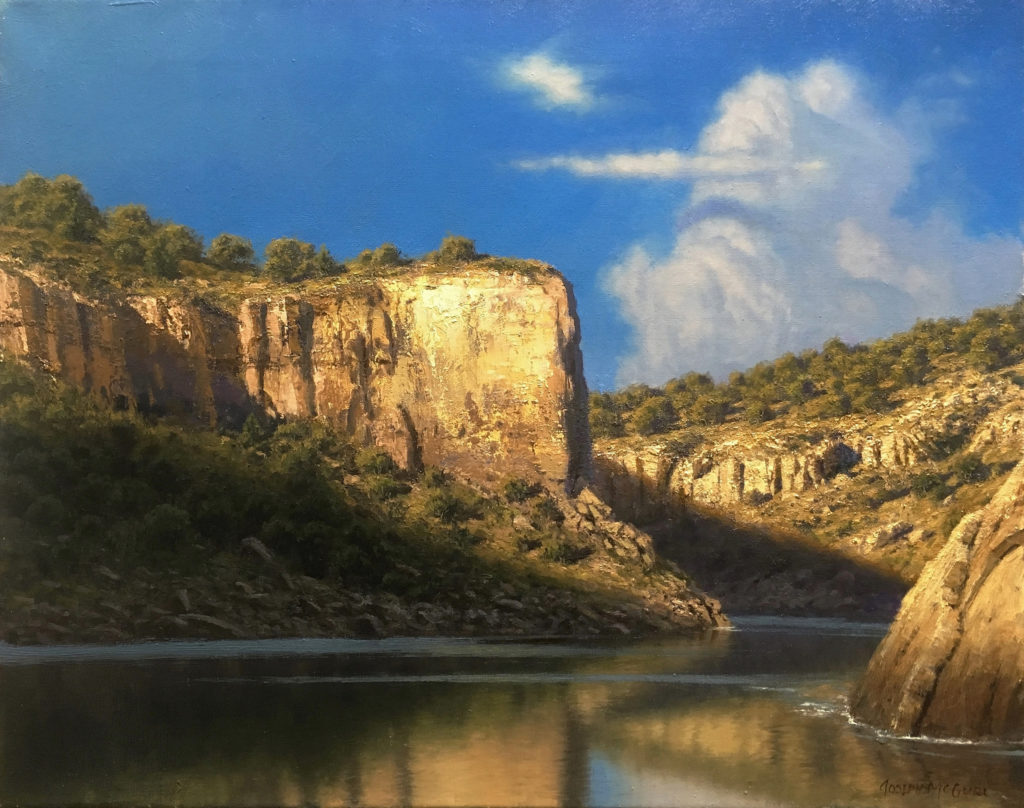

McGurl’s studio work builds on his plein air paintings, exploring, refining, and sometimes dramatizing themes and features that have aroused his interest outdoors. One theme that keeps recurring is an image of a dazzling reflection in water. In some of the studio paintings, this has been pushed to a near visionary statement, an almost otherworldly blazing light.

“It’s a theme I’ve been working on a long time,” says the artist. “The first painting was when I was still in college and I was looking at Quincy Bay in the glare of the sun. I painted the water blue and the glare white and I thought it looked cool. Then several years ago I was painting in Maine. Looking at the glare on the water, I wondered if I could paint it. I became fascinated by the effect, so whenever I’d see it, I’d paint it. A lot of times I like to investigate something over time; the more insight I get, the better I get at painting it.”

McGurl’s fascination with reflected glare seems to involve his somewhat spiritual attitude toward light. “I’m actually painting something that doesn’t exist,” he says. “If you move to the side, it disappears. It’s not an object, and it’s moving, and it’s impossible to match because all you have to work with is white paint. The challenge is: how do you make this white paint look like it glows? And of course the answer is that you have to adjust all the adjacent color values and you have to do things in the right proportions. If you put in too much glare, it’s just going to look like white paint. So how much glare do you put on there, and how does it affect adjacent colors and distant objects?”

As well as the high drama of glare, McGurl’s plein air and studio paintings share an obvious passion for the more subtle effects of light, how it creates delicate shifts in color temperature and tone in quieter passages. This results in a surprisingly rich and complete sense of an image in his outdoor work. The studio paintings not only refine light effects, but also explore ways of adjusting the drawing for dramatic effect.

This can be seen in his painting “Morning Sunshine,” where the plein air study creates a balanced, thoughtful, and delicate view of a cliff rising above a river. In the larger studio painting, he has redrawn the cliff formation to make it more dramatic and brought in more rocks on the right in the foreground. He’s also added a towering cloud formation in the sky. The result gives a more visionary and transformative feel to the painting. This ability to manipulate the components of the picture comes from a deep understanding of nature, and is clearly directed by the artist’s intimation of spiritual forces at work in the world.

Asked how his pictures relate to the viewer, McGurl says, “I want them to feel included in the experience I’m painting. I want them to be the first person there, to have a sense that they are looking at a sunset rather than a picture of a sunset. I often don’t put figures in, because if the viewer sees a figure they say, ‘Oh, it’s a painting of a person looking at a sunset.’ The figure has such a strong presence it’s hard to ignore. With plein air painting, I want the viewer to feel what I felt, to have this sense that there is so much more to our existence than what we see superficially. Through my art, I get close to the big questions. I want the viewer to feel that, too. What is reality? What is our purpose? What does it all mean?”

These are questions that may never be resolved, but asking them has spurred McGurl to produce a body of truly magnificent paintings.

> Click here to subscribe to the free newsletter, Plein Air Today

> And click here to subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue!

> Join us January 27-30, 2021 for Watercolor Live!

Excellent work, Joe, as always!

Thank you for taking the time to fill this article with lots of practical and thought provoking information! I have never tried Sight-Size Drawing with a view finder like that. I hope to do so soon!

I also loved reading about how you are continuing to stretch yourself and keep learning more about painting challenging subjects like the glare off of water…how you do that without going blind is beyond me!