Noted painter Joseph McGurl wraps up this series by discussing Frederic Edwin Church’s studies of icebergs. PleinAir Today thanks Joe for sharing his knowledge during the last few months.

For the last of these articles, I am returning to where we started, with Frederic E. Church. Church was an incredibly sensitive observer and skilled interpreter of the natural phenomena that he traveled the world to experience firsthand. He was adventurous, particularly for the mid-19th century. His journeys took him to South America, Europe, the Middle East, and, as can be seen here, to the North Atlantic. Church chartered a schooner to bring him to the coast of Newfoundland in 1859. From aboard ship, he made numerous studies of the icebergs he encountered there. As with the painting in the first article of this series, “Clouds Over Olana,” once again we see Church as an earth scientist investigating the physical reality of the natural world.

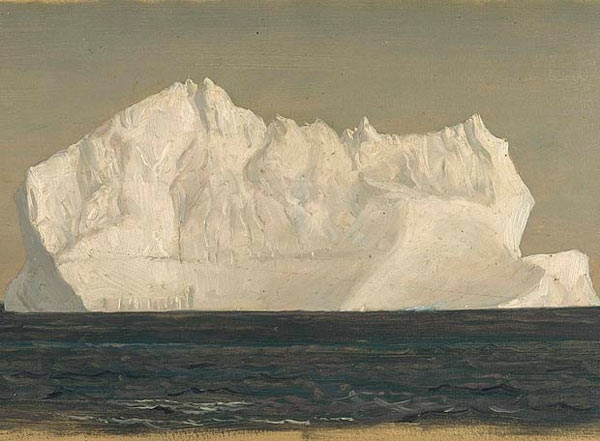

These iceberg sketches are particularly intriguing because they lead directly to one of Church’s most important studio paintings, “The Icebergs.” They were Church’s reference material, and because he spent so much time making dozens of sketches, he became intimately familiar with the characteristics of icebergs. He came to understand their structure; how they float; how ice calves off, creating their sculptural qualities; and the effect of light on all that whiteness. In these sketches, Church paid careful attention to form, and his understanding of light and shadow helped him describe the different planes, surfaces, and textures. This is important when dealing with a monochromatic subject.

“Twilingate, Newfoundland,” by Frederick Edwin Church, 1859, oil on paper, 12 x 18 1/8 in.

Equally important is the control of color and value when the subject is large and white. White is seldom pure, because it reflects the colors of its environment. This can be seen in “Iceberg Flotante,” where Church incorporated some of the warm coloration of the sky onto the tone of the iceberg. In “Twilingate, Newfoundland,” the icebergs take on a cool purplish tone similar to the sky colors found in the painting. This creates harmony; therefore, the objects blend naturally into their environment. Church also painted the sky slightly dark to avoid a white, pasty coloration, and he sets off the whiteness against a deep-colored ocean to create further contrast and value range.

“The Icebergs,” by Frederick Edwin Church, 1861, oil, 64 1/2 x 112 1/2 in.

The culmination of those studies, their raison d’etre, is the monumental studio painting “The Icebergs,” completed upon his return. Here, we can see Church incorporate many of the features he observed when making his sketches. By the time he began the studio painting, he had a thorough understanding of his subjects, allowing him to exploit their characteristics and create an intriguing and scientifically accurate depiction of a subject few people had ever witnessed. It is interesting that he included the broken mast. This may have referred to an expedition that was lost in the arctic a few years before, and it also may refer to the dangers of crossing the North Atlantic in the winter … 50 years before the Titanic.