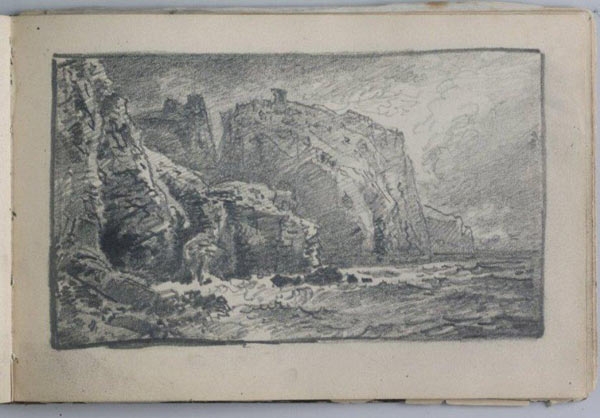

In this series, noted painter Joseph McGurl discusses plein air paintings by past masters that he finds instructive or inspiring. This week: a sketch from one of William Trost Richards’ sketchbooks.

William Trost Richards was one of the leading American 19th-century landscape painters. He was a member of the Association for the Advancement of Truth in Art, which was the American counterpart of the English Pre-Raphaelite movement. These artists were heavily influenced by the English art critic John Ruskin and his book Modern Painters. Ruskin believed that fidelity to nature was paramount, and the work of God could be found in nature’s smallest details. Characteristics of Pre-Raphaelite painting include an accurate observation of the subject and meticulous attention to detail. In his quest to portray nature accurately, Richards filled numerous sketchbooks with landscape and seascape drawings in graphite, ink, and watercolor. This sketch was included in one of his books from his two-year trip to Europe in 1879-1880. This book contained 86 drawings.

In addition to carefully observed and rendered detail, Richards’ paintings often convey a wonderful sense of atmosphere, perspective in the recession of the landscape, convincing form in the topography, and a sense of movement in his portrayal of the ocean. Although this sketch is looser and more gestural, it contains many of the sensitivities of his finished seascape paintings. If we squint, the impression is of a carefully rendered drawing because the value shifts are so precisely recorded. Here we see an overcast day; the hazy atmosphere obscures the features, making them less distinct and paler as they recede into the distance. Richards accomplishes this effect by careful tonal and line control. All of the pencil marks in the foreground are bolder, darker and more aggressive than those in the background. The forms become more indistinct and generalized as they recede, gradually reaching the distant headland, which is defined by just two lightly drawn shapes and values.

Richards creates linear perspective by his use of overlapping headlands. He also uses the perspective of the ocean waves to help move us into the distance. The foreground waves are larger and overlap the waves behind. In the distance, we can only see the crest of each wave because the troughs are increasingly obscured by the crests. This stacking of the waves helps the plane of the ocean recede into the distance. However, as well as a receding ocean, Richards also creates a moving, dynamic ocean. His pencil marks representing the dancing wave peaks convey energy and movement. The strongest value shift is where the breaking wave meets the rocky shore. This creates an energy contrast between the foreground and the softly rendered distance, thereby reinforcing the difference between things that are close and things that are far.

Richards is also interested in examining the topography and creating a sense of form. By clearly delineating the lighted and shady sides of the rocky promontories and simplifying the overall shape, his depiction of those formations appears solid and three-dimensional. It was important for Richards to carefully observe and interpret the natural world, and by doing so, he was able to refer to these small drawings to aid him in creating his large, majestic studio paintings.