When first-time author and plein air artist Deborah Paris stepped into Lennox Woods, an old-growth southern hardwood forest in northeast Texas, she felt a disruption that was both spatial and temporal. Walking the remnants of an old wagon trail past ancient stands of pine, white oak, elm, hickory, sweetgum, maple, hornbeam, and red oak, she felt drawn into a reverie that took her back to “the beginning, both physically and metaphorically.”

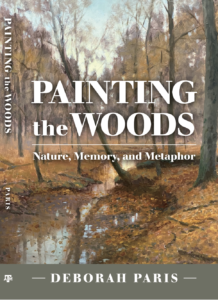

The following is an excerpt from her new book, “Painting the Woods: Nature, Memory, and Metaphor” (Texas A&M University Press).

From “Painting the Woods: Nature, Memory, and Metaphor”

BY DEBORAH PARIS

(deborahparis.com)

Pure Seeing

For landscape painters, “seeing” is a term of art, referring to a certain way they learn to see nature as motif. In general what this means is that landscape painters are trained to see nature as component parts consisting of the building blocks of picture making—shape, value, design, color. As an artist, I was trained to see it painted—that is, to look at nature and visualize the translation from three-dimensional reality to a painted surface before I ever started to paint. While looking at a row of trees in the distance, for example, I would think about what color I needed to mix to achieve the illusion of a particular light effect, or about what elements of the scene needed to be edited in order to make a more compelling design. The directive to see it painted is not bad advice. In fact it’s essential at some point in the creative process.

During my many years as a plein air painter, I was concerned with capturing specific effects and appearances in the natural observed world. So my time outdoors was devoted to creating art. But because of my focus on picture making, transcendent moments could not occur during those times. Painting, whether done in the studio or outdoors, is a series of problem-solving decisions, so the mind and eye are alert and constantly sorting through relevant data and making choices—comparing values, mixing the right color, editing and rearranging. The process of translating nature into a work of art left little room for simply experiencing the natural world, without any thought of how to paint it.

That kind of analytical problem-solving seeing, no matter how essential for the art-making process, did not foster the connection and deeper understanding I craved. In fact, it short-circuited that process. What I needed was a new way of seeing—a way that would allow me first to simply experience nature and strive to be a part of it. As a participant rather than an observer I could see it for what it was—nature, not motif. I call this Pure Seeing.

As a child floating in that pond I experienced nature in that way. Later, as an adult, I also had fleeting moments when my sense of connection was almost overpowering. In the nineteenth century these kinds of experiences were described as transcendent or sublime and included interactions with nature that produced feelings of awe, reverence, astonishment, and even terror or fear. In nineteenth-century Romantic poetry and painting, these ideas reached their height, and poets and artists went in search of such experiences by viewing awe-inspiring scenery or witnessing fierce storms or other natural phenomena. Even Thoreau was not immune to this cultural trope, and he ascended Mount Katahdin in Maine in search of it. But he eventually found sublimity in his own backyard, as it were. When he returned to Concord and Walden Pond, the woods and fields there provided all the awe and wonder he ever needed.

Drawing Sets You Free

I opened my sketchbook and attached small plastic clamps to hold the pages down on each side. I placed the sweetgum ball on the blank left-hand page so that its shape and three-dimensional quality stood in relief against the pale cream of the paper. A slight cast shadow darkened the paper underneath it and to one side, shaped like the pointy profile of the ball. I reached for three pencils—a 2B, a 4B, and a 2H—a small piece of a kneaded eraser, and my Tombow Mono eraser with its small round tip. I started to draw.

Intimate sympathy. It’s a phrase that might have been written by Thoreau, whose fascination with the workings of the natural world fed his understanding of nature, as well as his philosophical ideas. For the landscape painter, Pure Seeing can heighten our attention to how nature is crafted and deepen and transform the aesthetic relationship between artist and subject. Drawing is the natural outcome of that commitment, an exploration of how things are made as well as how they can be translated into pictorial form, and an invaluable tool in landscape painting.

“Painting the Woods: Nature, Memory and Metaphor” explores the experience of landscape through the lens of art and art-making. It is a place-based meditation on nature, art, memory, and time, grounded in Paris’s experiences over the course of a year in Lennox Woods. Her account unfolds through the twin arcs of the changing seasons and her creative process as a landscape painter.

In the tradition of Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, narrative passages interweave with observations about the natural history of Lennox Woods, its flora and fauna, art history, the science of memory, Transcendentalist philosophy, the role of metaphor in creative work, and even loop quantum gravity theory.

Each chapter explores a different aspect of the forest and a different step in the art-making process, illuminating our connection to the natural world through language, comprehension of time, and visual depictions of the landscape. The complex layers of the forest and Paris’s journey through it emerge as metaphors for the larger themes of the book, just as the natural world underpins the art-making drawn from it. Like the trail that winds through Lennox Woods, memory and time intertwine to provide a path for understanding nature, art, and our relationship to both.

Reviews:

“With a pure vision and focused interest akin to that of Thoreau, Deborah Paris has left her mark on Lennox Woods. Her depiction of those woods, both in words and in pigment, is transcendent.” —T. Allen Lawson, artist

“Deborah Paris takes us on a marvelous, thoughtful ramble through Lennox Woods, weaving together history, memory, and metaphor. Through a seasoned artist’s eye and keen intellect she brings together past, present, and future in the lifecycle of the forest and how it mirrors our own existence. Through her medium of painting she presents the imperative of deep, sustained connection to her subject and a profound sensory delight in taking the time to slow down and see more deeply. A lovely reminder for us all.” —Joe Paquet, artist

Deborah Paris is a landscape painter whose work has been exhibited at Laguna Art Museum in Laguna Beach, California; Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, Texas; National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City; Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa; and other distinguished venues. Making her home in Clarksville, Texas, she teaches and lectures nationwide.

Plein Air Today covers artists and products we think you’ll love. Linked products are independently selected and linked to for your convenience. If you buy something using a link on this page, Streamline Publishing may receive a small share of that sale.

Visit EricRhoads.com to find out all the amazing opportunities for artists through Streamline Publishing, including:

– Online art conferences such as Plein Air Live

– New video workshops for artists

– Incredible art retreats

– Educational and fun art conventions, and much more.

> Subscribe to Plein Air Today, a free newsletter for artists

> Subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue