In this series of articles, Utah artist J. Brad Holt talks about what artists are seeing as they look at the landscape. Holt studied geology in college and is attentive to what the rocks suggest in the scenes he paints.

On the day that I was born, August 17, 1959, half of a mountain fell into the canyon of the Madison River near Hebgen Lake, Montana. The massive landslide was triggered by a 7.5-magnitude earthquake, the largest to hit the region in historical times. Property damage was low in this sparsely inhabited region west of Yellowstone National Park, but unfortunately 28 people were killed when the slide covered a campground. The new lake that quickly formed behind the slide is popularly known as Quake Lake. This event is an example of mass wasting, a catch-all term that we use to refer to the work of gravity on the landscape. Rock falls, slides and slumps, debris flows, mud flows, and soil creep are all examples of mass wasting.

“Vishnu, Brahma, and Zoroaster, Afternoon Light,” by J. Brad Holt, 2013, oil, 9 x 12 in.

As a youth, I spent a summer working at the Grand Canyon, slinging hash browns and French toast at the North Rim Lodge. A comment that I heard repeatedly from visitors was some variation of how difficult it was to believe that one river, even one as mighty as the Colorado, could have carved so vast a canyon complex. We commonly hear that the canyon is the product of erosion, but this is not strictly true. It is the product of erosion coupled with mass wasting.

The question is resolved by looking at it from a geologist’s standpoint. The Colorado River, and a few major tributaries such as the Little Colorado, Bright Angel Creek, and Kanab Creek, are responsible for carving their own beds. This carving creates depth, and steepness. The bulk of the canyon was then formed through mass wasting, as rock layers of varying strength attempted to reach some sort of equilibrium. The property of steepness is a thing of inherent instability. Gravity puts a strain on the outer faces of rock layers, and depending on the steepness of the slope, sometimes it doesn’t take much of a trigger to cause them to fail.

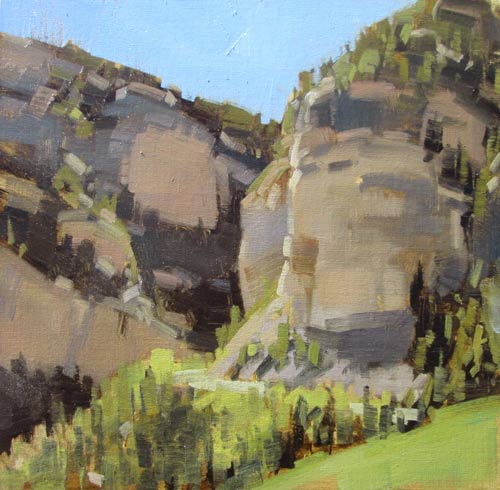

“Cedar Canyon Gorge,” by J. Brad Holt, 2014, oil, 12 x 12 in.

The pitch at which a slope of rock and soil aggregate will rest without sliding is called the angle of repose. This angle is governed by the size and shape of the debris particles. In much of the semi-arid West, the angle of repose is somewhere around 35 degrees. Those of us who are desert landscape painters have this angle burned into our DNA. It is the angle of the talus slopes that give the mesa and canyon country so much of its beautiful physical form. But we should also take from them a warning: A talus slope is a sign that the cliff above it is retreating. It is not a place to build your house. It is not a question of if more rock will fall, it is a question of when.

My friends and I recently painted in the middle part of Cedar Canyon, along Highway 14, just below the “gorge” section of the canyon, opposite to where Ashdown Gorge branches off. The gorge is composed of buff-colored Cretaceous Age sandstones of the Wahweap and Straight Cliffs formations. Under these ledges are gray talus slopes made up of clays, mudstones, and shales of the Tropic formation. This area of Highway 14 is notorious for landslides. The road has been repaired here half a dozen times in the last couple of decades.

Thin lenses of coal occur in these formations, and historic mining activity has contributed to the instability of the slopes in this part of the canyon. The last repair, a couple of years ago, was massive, and expensive. We stood on part of this reconstructed area as we painted, and we noticed that a number of sizeable cracks have developed that were not visible last year. I fear that this section of the highway will never be free from trouble. Heavy precipitation, frost heaving, earthquakes, and man-made slope disturbances are all triggers that can initiate fresh episodes of mass wasting on slopes that are just below the threshold of equilibrium.

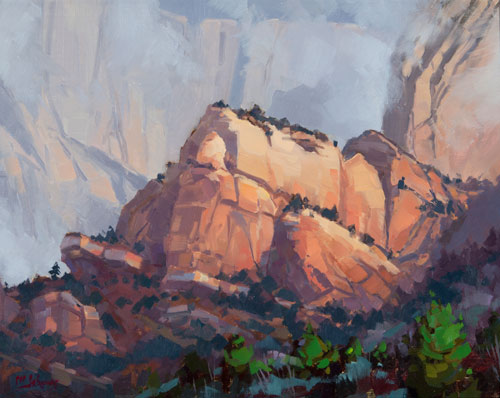

“Kolob Storm Colors,” by Mary Jabens, 2015, oil, 11 x 14 in. Studio piece

The cultured landscapes that we build around our homes offer mute testimony to our innate understanding of rock, soil, and gravity. When we place large rocks and boulders into our gardens, professionals will advise that more than half the rock be buried. Unburied boulders lying on the surface of the ground are aesthetically disturbing at a subconscious level. They can trigger our fight-or-flight response because we instinctively sense that they are unstable. When we bury more than half the bulk of that expensive rock, it becomes more stable-looking, and thus more pleasing as a decorative element.

This dynamic can extend itself to our artistic compositions. The tension created by vertical visual elements is relieved by the consequent diagonal elements, which lead to their ultimate resolution in the quiet stability of horizontal design elements. The interplay of these abstract elements of composition creates an unconscious subtext that influences how we feel about various landscapes.