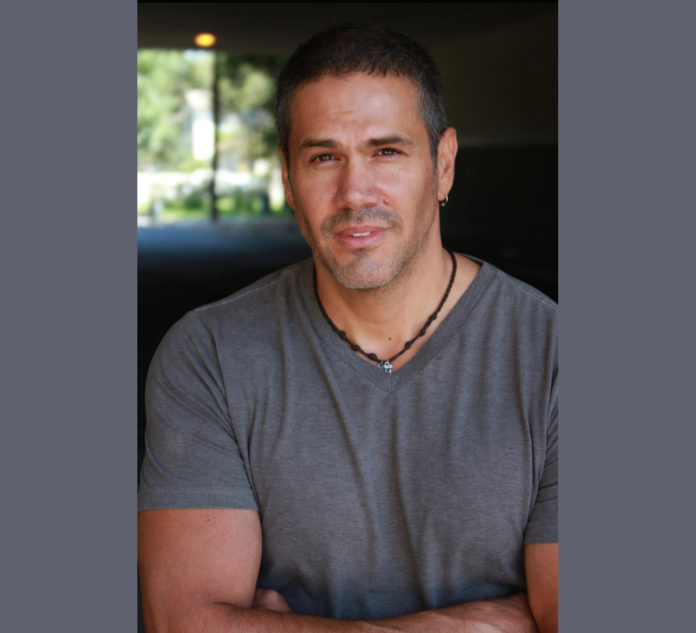

Welcome to the PleinAir Podcast with Eric Rhoads – rated the #1 painting podcast in Feedspot’s 2021 list. In this episode Eric interviews plein air painter and former production designer for DreamWorks Animation Mike Hernandez. Mike shares how he learned to channel his fear into creative energy and the related near-death experience that left him thinking, “What am I doing? I wanted to be an artist.” This story will have your palms sweating.

Bonus! In this week’s Art Marketing Minute, Eric Rhoads, author of Make More Money Selling Your Art, answers the questions, “Does my art website and newsletter need a catchy title?” and “Are there any traps that artists can be aware of and avoid?”

Listen to the PleinAir Podcast with Eric Rhoads and Mike Hernandez here:

Related Links:

– Mike Hernandez online: https://www.facebook.com/Mikegouachehernandez/

– Plein Air Live: http://pleinairlive.com/

– Paint Russia: PaintRussia.com

– Streamline Art Video: https://streamlineartvideo.com/

– Eric Rhoads on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/ericrhoads/

– Eric Rhoads on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/eric.rhoads

– Sunday Coffee: https://coffeewitheric.com/

– Plein Air Salon: https://pleinairsalon.com/

– Plein Air Magazine: https://pleinairmagazine.com

– Plein Air Today newsletter: pleinairtoday.com

– Submit Marketing Questions: [email protected]

FULL TRANSCRIPT of this PleinAir Podcast

DISCLAIMER: The following is the output of a transcription from an audio recording of the PleinAir Podcast. Although the transcription is mostly correct, in some cases it is slightly inaccurate due to the recording and/or software transcription.

Eric Rhoads 0:00

This is episode number 208. Featuring the amazing painter Mike Hernandez.

Announcer 0:18

This is the Plein Air Podcast with Eric Rhoads, publisher and founder of Plein Air Magazine. In the Plein Air Podcast we cover the world of outdoor painting called plein air. The French coined the term which means open air or outdoors. The French pronounce it plenn air. Others say plein air. No matter how you say it. There is a huge movement of artists around the world who are going outdoors to paint and this show is about that movement. Now, here’s your host, author, publisher and painter, Eric Rhoads.

Eric Rhoads 0:56

Well, thank you Jim Kipping and welcome everybody to the plein air podcast. The plein air podcast has been rated the numero uno number one and feedspot 2021 Top 15 painting podcast list. Thank you for that. Thank you for making it happen. Welcome, everybody. And welcome to March last year at this time, I was in Russia shooting a documentary and shooting two art instruction videos with one of the top Russian masters Nikolai Blokhin, which are amazing. Anyway, I’ve got some really wonderful memories of that trip. I got to meet the heads of the…, the Reppin art Institute’s the two biggest and probably most important art schools in the world and also had the got to meet the heads of the top museums there. It was really wonderful Russian painting is just so wonderful. It was cold I got to paint but it was called and I’m going to be back in September God Willing with a group of about 50 people who are going with me to Russia painting trip at paintRussia.com is sold out. But there is a waiting list just in case we can open some more seats. So we’ll hope so well hope so. But you never know. Last week we had record numbers of people signing up for plein air live or online summit with top artists. We got a big big lineup of really amazing artists, you should check it out anyway. Oh, there are still some more big artists to be announced and you can save some money Still, if you sign up at pleinairlive.com. This is a perfect thing for spring training, getting you ready and tuned up for your best painting over the summer. If Of course travel is allowed, of course, you can still go out and paint but it’s a good time. great chance to really learn from the masters. And there’s a beginner’s day for people who want to learn the ropes on plein air painting and learn all about the equipment and all the other things that you’ve got to learn and understand. That is at PleinAirLive.com. Now this is the final month the last month the end of the year. When it comes to the annual plein air salon we normally award the awards at the plein air convention which has been cancelled this year. So the last chance to enter is March 15. It’s a short month we just ended. The other competition the awards are about to be announced for that but the march competition is ending on the 15th because we have to have plenty of time to get the annual awards figured out and get them ready and we’re going to present them on the Plein Air live broadcast and so you want to be part of that. There’s a cover of plein air magazine and $15,000 in cash up for grabs and many many more cash prizes. We do only cash prizes all cash prizes. No pretend prizes. Anyway, pleinairsalon.com is where you go before March 15. And we’ve got a new video out by the way with last year’s winner Dave Santillanes. He’s and you should check that out at https://streamlineartvideo.com/. All right. It’s hard to believe this but this issue of plein air magazine is going to be the 10 year anniversary issue one of them we’re celebrating all year. This is an article on that first feeling viewers often struck by Tiffany Mags choice of materials squash digital, and the medium is not the message this California painters has many things to say and you want to check that article out also. In plein air today our newsletter a glimpse of our plein air heritage as we focus on an artist which you’re going to love and his philosophy on plein air painting or nothing. That’s kind of how I feel. Kind of. Anyway, coming up after the interview, I’m going to be answering your marketing questions in the art marketing minute. But let’s first get to our interview with plein air painter and former production designer for DreamWorks Animation. It’s Mike Hernandez. Mike Hernandez, welcome to the plein air podcast.

Mike Hernandez 4:38

Hi, Eric. Thanks for having me on.

Eric Rhoads 4:41

We are very excited about this. You and I have done some projects together. You did a live workshop here in Austin online. We’ve done some videos together. And you’ve got an incredible background and career and so we’re going to dig into that today.

Mike Hernandez 4:59

All right, that’s Get so where do you want to start? What?

Eric Rhoads 5:02

When did this whole interest in in art begin for you?

Mike Hernandez 5:07

For me, you know, it’s weird to kind of, I don’t know, I kind of grew up in a family of art. My father used to work for the aerospace industry, he worked for Northrop. And he was a commercial artist. So he did most of his work, obviously, yeah, he did most of his work at, you know, at the studio, but he also had his own little room that my brother and I would break into, you know, just about almost every day, you know, and break into his markers. And back then they had some of the most toxic, but incredible colors you can use, we were getting high up all the bad stuff. But we broke into the markers, we broke into all the color pencils. And you know, we were looking at my dad, you know, he had these beautiful duotone gloss paintings up on his wall of you know, test flight simulation type scenarios that he was painting for Northrop, and advertisements and illustrations. And so we would kind of copy them to see if we can replicate what my dad was doing. So at some point, my father found us like years later, he kind of knew we were getting into stuff and kind of scolded us lightly because I think he liked that we took an interest to it. And I was always the kid in high school that went that extra mile with the PT folder drivers, you know, and other students would come up to me and ask if I would do a little bit more work on their PT folders. And then of course, the desk was always a fun thing, you know, my head teachers who, you know, got me in, I was in a lot of trouble for drawing on my desk quite a bit. However, they couldn’t help but you know, take interest in some of the things that were on that debt. But that’s pretty, pretty cool stuff. You know, what I got to like.

Eric Rhoads 6:43

What kind of things were you drawing on your desk?

Mike Hernandez 6:51

I don’t even remember now what it was, it must have been, you know, all we figured is things like faces, you know, it was I was never into like character, right? My image, my imagination never went further than reality. At that point. It wasn’t until I got into, you know, the industry later, but it’s better that he was all about, I like eyeballs. So I might draw an eye, you know, and I focused on the iris and making the iris look really cool. And then, you know, I haven’t when I was at home, I tried to figure out how to draw a hand. And if I was onto something, when I got to school, I got lazy, I’d start continuing on the sketchbook or I would start, it would go from the sketchbook off the sketchbook and continue on to the desk. or there might have been a girl that I was liking. And she was, you know, kind of attractive. And I had a crush on her. And I would maybe draw pictures of her profile from a distance. kind of creepy, right? But that’s kind of what I was doing as a kid. Definitely.

Eric Rhoads 7:42

seventh graders go. So did your dad. Your dad was an illustrator. Did he ever at any point say, hey, let me show you how to do some stuff.

Mike Hernandez 7:53

He did. You know, he did. Eventually, you know, come in. And you know, I remember one of the biggest hints of advice he gave me when I was struggling with you know how to draw landscapes from photographs or mountains. And he said, you know, put blue in everything. I said, But Dad, I don’t see blue in that part in that part. because trust me, it’s in there, especially when it’s a landscape. Blue is inherent in everything. And I didn’t know what he meant by that time, at the time, but I went ahead and did okay. And you know, I started putting more blue in my paintings, which is contradictory to what I teach nowadays, I always tell students, you know, not to put too much blue into their their landscapes because it tends to flatten it out.

Eric Rhoads 8:37

Then what? So you’ve, you’ve learned that that’s not necessarily the right advice, but it was time.

Mike Hernandez 8:44

At the time, it was the right advice, because I was using too much muddy colors, basically, you know, I think my dad, what we’ll do is trying to say is mix your colors, you know, mix more colors in what seems obvious if there’s a building in the distance or a rock and it looks Brown, you know, it’s not just white with brown, you might consider putting a little bit of blue or another color or green or something to it, to give it a variation of that color. And so that was a profound message he gave me when I was a kid, you know, and so I started incorporating more blue into areas that didn’t think had it, which is interesting. So now when I teach class, a lot of times that’s that is a note I’ll give students for example, they’ll have the sunlight hitting the dirt, and these guys are using straight white with yellow ochre. But what they’re forgetting is that we’ve got that whole canopy above our head of blue sky, you know, that big blue canopy. And when the sun isn’t directly overhead and it’s at an angle, well, that canopy blue hasn’t You know, it has an effect as it filters through all the warm rays. It kind of mixed through that at a three quarter angle and it has an effect on the sunlight. of the temperature of the sunlight. The color of the local the local color of the object is hitting and some of the blue that comes through in Because with that, and then that’s something I’ve kind of started to teach students. And then whenever I teach that I tell students do you need to put a little bit of blue in there? You know, maybe you make you warm up the blue by adding you know, ogres and things to it, but the blues in there. And then I’ll recall what my dad said it wasn’t until much later in life was like, like, I guess that’s what my dad meant by, you know, pit blue and everything.

Eric Rhoads 10:21

Well, you know about blueing agent.

Mike Hernandez 10:25

No, I don’t.

Eric Rhoads 10:27

Back in the day. I don’t know what day that was. But to make whites look whiter they put blue in it.

Mike Hernandez 10:37

Right, I didn’t know what that was called. I didn’t know there was a term for it. But I do recall, you know, for me, when I’m doing paintings, when I get to the highlight, especially if it’s a warm object that needs a highlight, the wider it goes, the higher it didn’t, the intensity didn’t seem to be quite as bright. So I would usually pick it with a little bit of green and blue or a touch of magenta and blue in the white just to kind of feel it vibrate a little bit to see that it’s separate as a highlight. So it’s actually interesting term.

Eric Rhoads 11:08

Yeah, well, there you go. bluing agent, I don’t know probably withholding agent blueing agent is what I remember. And, and I remember from laundry back in the, you know, when I was a kid, that, that they they would always touch put it you want your whites wider while we have blowing agent in our, in our laundry detergent, they still probably put it in there, you know, if you look at tide, tide comes out blue. So maybe there’s something to shoot, maybe it’s such a die of some sort.

Mike Hernandez 11:38

Yeah, if you look at your blue scales, and this is actually something I had taught students and without even knowing it was called Blue agents. But I a lot of notes I’ve given recently for students painting buildings that appear pure, pure white, I’ll tell them, the only reason that that building looks pure white is because it has blue in it, and the rest of the landscape around it is very warm. And then if you have a building that has a cooler tint of light to it, it appears cleaner, it is going to appear whiter, as opposed to just taking as much white as possible, if you tint that little bit of blue, into that building without having to go all the way to right because that’s always something that we try to avoid is going 100%, white or 100%, black, you just kind of lose color completely or Eagle flat, or Eclipse stay within value. You know, I said if that building looks like it’s screaming white, it might, you know, you might be able to get that same effect by you know, creating a contrast of a darker color next to it. And then put in a little bit of blue in that light, or that gray make it a cool gray and it’s still a white.

Eric Rhoads 12:44

That’s terrific. Well, you teach color, and you teach composition, and you teach a lot. So let’s go back and finish this, this biography part of this, and then we’re going to go into the evolution. So you’re doing some stuff in school, and you’re getting in trouble for writing on the desks and putting pictures of pretty girls on the desk.

Mike Hernandez 13:08

Getting a bad reputation. And, and in any of that time that I feel like I was going to be an artist at all, really. It was always hobby, it was always just for fun. You know, even in high school, I was, I get the reward for being the best artists in the school. But I never thought well, that’s, that’s my, that’s my career, I’m going to be an artist one day, I never thought about any of that. I never considered it.

Eric Rhoads 13:31

Even though that’s what your dad did for a living.

Mike Hernandez 13:34

Exactly. And again, the only reason I did what he did is because, you know, it was it was the coolest thing I respected my father, you know, and I respect my father with a great, you know, with the greatest and to see what he does, it’s like, well, I want to do what he does. So not necessarily do what he does for me, but I just want to do what he’s doing. And it looks interesting, and it’s creative. But High School in high school was just, again, rewards after rewards and awards after awards. And, but never an inkling to do something artistic in the professional sense. And no art art teacher at our school ever said, Hey, you know, you can make a living doing this. Um, I recall that there were probably discussions like that. And for me, it was just like, yeah, I’m probably going to be an astronaut, though, you know, or probably gonna, I’d rather do something, you know, a little more in depth, like, you know, create automobiles or something like that, which of course, there was no chance in hell I had. I was ever going to do anything like that. But I, I think my aspirations at the time when I went after high school finished, I just kind of dropped out, you know, and I just, I didn’t do anything for a few years. Except for rock lines. You know, I became just like an avid sport, rock climb, and I would spend many, many years in Yosemite, climbing the faces of the rocks and spinning, you know, spending nights upon a little, you know, ledge sweeping up there. So that kind of became the norm for me was just climbing.

Eric Rhoads 15:00

Well, you’re my hero. That’s pretty incredible to be able to do that.

Mike Hernandez 15:05

The only reason I did it is because I grew up with a fear of extreme heights. It was always my fear. And what the fear of heights taught me was that whenever you have that fear, let’s say you almost fell, are you looking over the edge, you ever notice just how much how much fright you get? Well, that fright also, is because of the the amount of energy in the intensity in that moment, you could actually channel that intensity in your favor as opposed to against you. So for rock climbing, I ended up doing that, of course, I did everything with ropes, you know, and protection. But I learned that there was a lot of energy in the fear. And if you learn how to channel it correctly, you can use it to motivate you as opposed to bring you down. But because I was out in nature all the time, I kind of felt like there was always that connection to nature. You know, the colors, the light, the atmosphere, all of that stuff, the organization of things. I was always connected to it. And it always brought me back to art because even when I was rock climbing, I was I still had a sketchbook. And I still drew all the time, you know, and it kind of went like this. So rock climbing day, and at some point, I needed to make money. So then I went to go work for a cable company called, I think at the time they were there Comcast now but they were charter cable communications back then. I remember that. What about you?

Eric Rhoads 16:24

Oh, did you really? It wasn’t charter cable world, but it was charter It was a broadcasting company.

Mike Hernandez 16:30

Yeah. So we headed as Charter Communications cable company in Alhambra. And I was the, you know, I was a poll auditor, which was I would go up and audit cable theft. So my job was to put on these these metal spikes on on their cold gas. And you put these metal gaps in the wrap around your ankles in your, in your your boots, and you gap up your z phone poles that had to be certified to do it. And I only reason I was drawn to do is because I was I love climbing things I was. So I was gapping poles, you know, and anytime there was another person who was too terrified because it was a dangerous job, and was terrified to go football to go check to see if there was a line connected that was illegally tapped in. That was my job, by the way as an auditor with to see if that line was still hot. And if it was still hot, it might have been that maybe somebody for you know, another tech person was lazy and didn’t disconnected after the customer decided they didn’t want it. So that way when somebody moves into an apartment, let’s say for example, and they say Oh, what’s that line, they plug it into their TV and get free cable and said didn’t know it came with free cable. It didn’t. It’s just that the guy the tech didn’t go up, or a tech sold that illegal box to somebody and then went up and connected it for them. Or you had the worst ones were just people who would maybe take the wire and they would fray it and they would they would just shove it in, they would climb up and risk their life and just shove it into the darn port and get a legal cable. So there was there was a big job for me and a few other people to do that we’d go to cities, and just claim these poles all day long and disconnect the legal cable service all the time. And then try to see if we can sell them on legitimate cable and make money and we get profits from it. But it kept me climbing all the time. And then I saw I started getting further and further away from the thought of ever doing art because there was an inkling and a time after climbing and sketching all the time out there. So I thought you know, I was really good at art. You know, maybe I could do something with it. Who knows, you never know. But then I started getting into the cable company. And it didn’t seem like it was a career choice. It just felt like this is what I was going to do for a little bit and then maybe, maybe I would reconsider art again. But then came you know, the apartment and the car and responsibilities. And before you knew it, I was like you know, I was getting married. And so okay, well, maybe this could be my career, I’m going to be a cable tech, I’m not going to be an artist. And so I embraced it. But it took this one day where I was gapping up a phone pole. And it was a big one, it was a 90 foot phone pole, 9090 foot phone pole. And those aren’t normally the height of these poles are usually not that high, but this one was really high. And I’m gapping up this pole. With all the confidence the world you know to implement these gaps. By the way, these little metal spikes, they’re only about an inch and a half to two inches long, but they only go into the phone pole about maybe a quarter of an inch. Now based on angle right if your angles off you slip and you’re not you holding on with your arms. And it isn’t until you get to the very top where you’re going to do your work that you take a belt from around your waist and put it around the pole and clip it to your belt again and lean out. So you’re still not that you could still fall down. It was a pretty dangerous job. So I was doing that one poll and I was getting up there and I had a friend down below who was watching me but he’s had a lineman down below. And I get to the top of that poll just about and I’m ready to secure and I gasped and I hit a part of the pole that was just deteriorated. We call it cinnamon stick and it just deteriorated and I fell in my hand reaches up and luckily I’m at one of the tension wires up there and luckily it wasn’t a hot electric wire in it. wiring, I’m grabbing it, and I’m struggling and it’s 90 feet down by fall, it’s over. And I’m panicking about oh my god, what am I gonna do you know, and so my, my guide down below is actually called a truck and I didn’t know what to do. And I barely got my feet over the wire and clip myself in and I’m hanging there suspended. And I’m safe for the moment. But I did to get the bucket truck guys over here and have them get me down. I’m a little shaken up. But while I was up there, I started thinking myself, What am I doing up here, I wanted to be an artist. I want to be an artist, I wanted to paint for a living, I wanted to go to art school, not do this, this isn’t worth it. I mean, if I’m going to die, doing something, I’m going to die. It’s something I love it better be I die because I ate too much cadmium orange or something, not falling off the phone pole that’s not worthy of my time, you know, or death by paintbrush? Whatever it is, I’d rather do something more legit.

Eric Rhoads 20:54

You often hear stories of people have clarifying moments that that was a near death experience and clearly a clarifying moment.

Mike Hernandez 21:03

Absolutely. You know, and I did after that, I was so terrified that I wouldn’t get the chance to you know, because I made up my mind at that moment, I’m gonna go to art school, I’m gonna, I don’t know how I’m gonna do it, I’m gonna get the loans, I’m gonna get scholarships, I’m gonna go to art school, I’m gonna somehow quit this job and get out of this. But I gave him a month, you know, obviously, that I was gonna leave. But I was so terrified that within that month, because I was so shooken up from that near fall, that within that month, I’m going to fall again, and I’m not going to get my chance. So they all understood, they laughed, and it was a good thing. My boss saw my potential as an artist, because I was always the guy that said, Make us posters here at the office, and they always like, you should be doing art for a living. And so I, you know, I he understood and respect my, you know, what I wanted to do, and he kind of laughed about it, because I’ll put you on light duty, you drive the truck, you know, and you hand the stuff and I left the company and I got a scholarship to go to art center. And they got me you know, almost half the coverage for school. And before you knew it, I graduated top of the class and distinction and was ready to do art in the field. You know, it was all up from that point. Oh, Art Center has a great reputation.

Eric Rhoads 22:16

And who did you study with there?

Mike Hernandez 22:19

Vern Wilson, he was one of my favorites. I remember him from the beginning. I mean, there was almost all the teachers at that time, you know, they were just, you know, I gotta say, in some, in some form or another were all my favorites. You know, Vern Wilson for head drawing, I remember his ability to just kind of wet and block arches paper, and then know where to put the dry marks for the lines. And he’s drawing faces and know where to put the blot where it needs to bleed. I could never understand that it was just an intuition that he would do. But I loved that class. You know, I thought I was going to be a figurative artist because I was just you know, like I said, when I was a kid drawing on desks, it was always figured eyeball pants beat then, and I really embraced that when I got to art school, it was all about anatomy, taking anatomy classes and figure painting. Never thought about animation. Never thought about environmental design. Fine Art was kind of my thing. You know, I studied under Ray Turner for quite some time. And you know, I think he had the biggest impression on me when it came to expression of color. You know, I thought everything I studied prior to that which you should you know, when you’re, you’re studying your your basics and art school should be all about the academics of color, right? You know, a plus b should equal c meaning blue plus orange should equal compliment gray. All of those things added up. You know, if you take white and gray at this percentage, you’ll get that number. And I thought okay, well, I need to learn the grammar of art first. So I did that. But when I took Ray Turner’s class, it wasn’t about a plus b equaling equaling C, it was like a plus b equals whatever it is you want it to be. And, you know, he taught me a whole new method to how to use color and his method. You know, he taught both head painting. And he taught a landscape painting class, he taught the first ever landscape painting class at Art Center, where you would actually go out and location and paint. But at the time, I first took his head painting class. And what I loved about it is he didn’t mix on the palette He mixed on the canvas, so he would just take gobs and gobs of color and load his brush up and slap it onto the canvas and just start mixing onto the canvas and taking risks. And so I thought, you know, I want to take this guy as an independent study, you know, to see what I can gain. So after its head pain class, I took an independent study with him and we did you know, I remember he gave us this assignment He’s like, go to that would go to the tool crib, at the school where they cut all the wood, wood block and all that and there’s a trash bin of all the leftover wood scraps, I want you to get all that stuff. And I want you to paint them all with jessalyn prep them and then I want you to just do you know as many head studies as you can in oil and then And he gave me just a stack of black and white photos to paint that he uses. So I started painting and inventing color. And I would come back to him and he says, Yeah, you’re still just going to literally your looks like you’re just trying to like this a skin tone and this and he goes, and I want you to take more risks. And I would come back and he’d say, That’s better, but it’s not enough. So then when you would do is scrape with a pellet knife, you’d go to his dirty pallet, big glass pellet, and all the mud leftover that he was about ready to throw away, he just took a big scoop of a couple of scoops of that he threw it on my palate, and he sent me home. He said paint with that. And so without much amount of pain, it was a bit of painting and sculpting. But then you learn a lot of things from those beautiful mixed colors, the further away you get from the primary colors, the more interesting the subtleties become. And then you could react off those things with using more saturated colors against them, and then in proportions, and then within hierarchy. And then you realize, Oh, it’s not about literally what you see in front of you. That’s art. It’s about the relationships with color, and how color works. When one color is put in proportion to another, and the hierarchy of those. So then he taught me that. Just because landscape shows you that warm colors are in the sunlight poucos in the shadow doesn’t mean you have to do that you have to counterbalance and balance it, to make sure that it’s appealing to the eye in nature is a good place to start. But it’s not the end all you can kind of break all those rules and make your rules there are no rules. But there’s good footnotes To start with, right you want your academics and then after that, so Ray Turner was really great. When using color, another artist I studied under was Donald Putman, you know, he’s, he’s passed on there, but he was a west southwest artists as well. And he taught me color, you know, that was, you know, he taught me the amped up version of color, which was to use a lot more saturation, but to take risks and say you can use blue for skin tone if you’d like, or green for skin tone. And then I remember I spent quite some time doing very overly colorful paintings and using a lot of purples and magenta things I was never taught to do when I was in school. Art Center taught you you got your number Yellow Ochre is, you know, I forget what they call that. What is this palette, not the Zorn palette was it? Like earth tones, you know, mostly like earth tones with one blue or something, which is a beautiful palette, like I will sometimes revert to that palette to then kind of, you know, remind myself that colors don’t have to be so sweet. But I got to a point where the colors are so sweet. And then I ended up having to come back and dial it in. But artists like that were fantastic, you know, that every artist I had at art center contributed in many ways. I mean, one example would be I don’t remember her name. Unfortunately, she’d kill me if she heard this. But she taught letter form. And letter form was one of the classes that gave me a lot of discipline on how to actually create a letter type without using the computer. And without using any rulers, or edges or French curves by hands, you had to draw out the letter form or an alphabet or write a word and then paint it in with a pink called pluck up a black and white. And it had to be ready like camera ready when it’s done. It had to be perfect. So it taught me a little bit about control and elegance. So every class had its thing that contributed to where I got today, you know.

Eric Rhoads 28:28

So you were one of those classes you mentioned you started going outdoors. So that must have been the first plein air experience.

Mike Hernandez 28:36

That was, you know, I never did paint outdoors. I always sketched outdoors and never painted. So I decided and the only reason I took it was because I thought it was going to be a nice break, you know, from indoor classes, you know, so when you know a couple of other buddies said, hey, let’s pick it together. So we can all camp out because it was basically three weekends for the whole term. We go out in a weekend, Friday, Saturday, Sunday and paint and camp out with, you know, returner and learn some landscape painting. And then that turned out to be one of the most pivotal classes I ever took, you know, I took a big interest to outdoor painting, you know, because that’s when I realized Well, all the colors, you know, that you take for granted in photographs. They’re all out here in nature, and they’re different. They don’t look the way they do in photographs. And it’s a different ballgame when you’re painting from life as opposed to a photograph. When you’re painting a photograph, you know, you don’t get the scope and scale of that environment. You don’t feel the atmosphere or smell what it smells like or you don’t get the sense of culture in that environment that you get from maybe the people or the animals that were there. All kinds of things bleed into the experience of being present in the moment. And it has an impression on what that artwork is going to look like when you’re there. You know, were you there at that landscape early in the morning within your impression of what it feels like to be up that early. The cool air that kind of lighting, all of that in the culture of where it was you were painting all leads into the results of what you’re going to learn. I didn’t realize that until, you know, I got into the animation industry, and they’re asking me to paint like, hey, do a color key. For a very sad morning in Europe. I’m like, Well, I have to look up other artists who’ve maybe done that to try to see if I can get a reference. Or if you painted, or you can kind of draw from life experience, right? To find out Well, maybe what was it like for me to be either in Europe, if I’ve ever painted there? or What does that culture like? And how does it have an impression on the colors? Or when you’re there talking to the people or seeing other artists? there? How do they paint that culture? What is it like, or how to pass artists? So plein air painting opened up a paradox of possibilities for what it meant to be outdoors in the culture and expose yourself to the environment that you’re going to paint as opposed to looking in a window of a photograph to paint from it?

Eric Rhoads 30:58

How did you end up in the animation industry?

Mike Hernandez 31:02

So that was interesting. Graduated Art Center with a lot of debt. And, you know, thank God for all of those. All of the scholarships and the grants and those helps. But yeah, I was still left with a healthy debt and needed to get a job. And again, didn’t think that I was going to get into animation. I’m thinking that most of my career here, my career path has in college was fine art, fine art, figurative and painting. And that was my portfolio and some charcoal sketches with no environment, no perspective, maybe one perspective drawing, but mostly Fine Art ish looking things expression of the body and the head and face. And I had friends who recently graduated Art Center, and they were working at Disney and they were working at DreamWorks. And, you know, I was talking to them. And that was, you know, saying, you know, Hey, I got a lot, I got a quite a bit of debt, you know, are they hiring over there. And they kind of chuckled and said, Yeah, but I don’t know, if your portfolio is kind of what they’re looking for. You need environmental stuff, you need set design, you know, you need some cinematic background, and I didn’t have any of those things. But I took a risk. Anyway. And so what I got to lose. So back in 98, I, or 99, I submitted a portfolio to DreamWorks. And funny things I got, I got in. But not only did I just get in, I didn’t even get in at the entry level I got an F, it’s kind of not really the top, the top would be production designer, art director, but I got in, in visual development is different back then than it was today. Back then back in the 90s. You know, visual development was a small department of like maybe 10 artists, who were the top of the chain of the food chain there who’ve already paid their dues in the layout department, the background painting department, you know, or the the roughly art department or character design, they’ve kind of already paid their dues, and all those departments. And so now they can be a visual development artist. Those are the artists that basically are in charge. Before anything gets made. They work with the director in the in the scriptwriter and the producers. And they start coming up with visions for what the show will look like. And then once their visions get brought off on they start to then hire, or they send that work off to the production teams who then go into production, the visual develop those artists then turn into the rough lead artists cleanup. So for me, I got all the way up there to that and I didn’t know what it meant. And I remember my first meeting, it was with Jeffrey Katzenberg at the time, and I just wondering, what am I doing in a room with Jeffrey Katzenberg and all these other artists. And they were pitching something for a show called syndet. And they had these amazing oil paintings, which is unheard of for visual development these days, usually everything digital, there was these over the top massive from wall, you know, from the ceiling to floor paintings, oil paintings for charcoal sketches that were massive and gorgeous. Just visions of what the movie Sinbad could look like, and all this gorgeous lighting. And I’m thinking is this the job that they got me into, they think I can do this, went back into my room and curled up into a little fetal position in the fear don’t belong in this position, I suppose. And then it turned out later, one of the the lead artists, you know, was, you know, I, I’ve come to respect him so much now because I know I understand what he was trying to tell me. But he said, You know, I saw your portfolio. And I I wasn’t one of the people who wanted you for that position. But it was a producer’s for some reason that that you had the chops and thought you should be here. And but I don’t think I think you need to be in another idea. You need to kind of work from the bottom up, you know, and so, I was determined after hearing that, and I decided, you know, so what they did is they said they were going to get rid of me because it’s not going to work out apparently maybe maybe the producers you know, and maybe they shut off half cannon on that and they went a little bit too far. Until they said okay, well we made a mistake, but you have three months. So decide what you want to do before we let you go. So what I did is I went to the layout department which was, you know, one of the more entry level departments where they were, you know, after the visual development processes done at the time, they were working on Eldorado and they were already painting the background, or they were drawing the background, I begged some of those artists like, you know, look at my portfolio, what is it I need, and a couple of them are really cool and suitable, this is what I would do. And so I just did, I started doing what they were doing, I’d go back to my office, I had nothing to work on. So I did these background drawing sketches. And after about two weeks, I then started showing these sketches to some of the other lash artists. And they’re like, that’s kind of cool. But I would do this and this. And then eventually, I took it up to the head of the layout department, and I showed him the work. And he just kind of smiled at me. He gave me a big smile. And he says, You know, I don’t know what to tell you. You know, they were at a Crux at that time in the studio, they were ready to lay off a lot of their departments of people who’ve been there for quite some time. And here I am a new person trying to get in while they’re going to be laying off a whole bunch. He said, You know, if the timing was different, I think he’d be great for this position, I just don’t know Ditalion. But other people got involved. And, you know, they saw the potential what I was doing, and for some reason, I made the cut after that, you know, though, and the layouts were only because they were starting to move towards 3d films. And they were going to get we’re going to break away from 2d animation. So I made the cut and eventually made it in. And from there, the story just went on, I was a layout artist for a few years, and I was the sequence designer. Then I got my first break when I actually got to art director, a TV show, our first animated 3d TV show, and I was our director on that kept going. It was called hidden, nobody will know what that show is anymore. It was the 16th Android show. It was the father of the bride, not Father of the Bride, the father of the bride. And it was an NBC TV show. And it was supposed to be huge. And you know, it was it was the biggest thing for me about working on that show. Not only was the fact that I got to you know, that was my first shot at actually, you know, art directing something. But I got to meet, secrete and Roy, you know, he went to Vegas, and I met the two guys, and Roy is just probably one of the most fantastic people I’ve ever met in my life. Such a sweet, really caring guy. And I totally can tell that he was absolutely into what he did. He was so vibrant. But it wasn’t unfortunately, just you know, months after that we got into production, he had that accident. And you know, his, you know, got bitten by a tiger on the throat. You know, and of course, today he’s deceased from from that wound. But that kind of hampered a little, you know, that put a damper on the show, you know, it is a little bit weird. And that wasn’t maybe the only thing I think the other thing that was kind of working against us was I guess our time slot was, you know, kind of up in a time slot that was more or less family more adult. So maybe maybe that had something to do with I don’t know. But you as you know, I think a lot of people know, when you’re going into this industry, everything’s a crapshoot, you give it a shot, you see if it’s gonna work, it either does or doesn’t. But I had a lot of fun working on that show, it was a blast. And in fact, some of the people who worked on that show are actually some of the bigger names, you know, in the animation industry right now who’s kind of made it made their way up the ladder. Some of them are now directors and their art directors and production designers and head of layout. You know, we all worked on that show from the bottom because it was a TD pipeline that was more aggressive than a feature pipeline, and we learned a lot from it.

Eric Rhoads 38:33

Well, when you’re in a more aggressive timeline, like that you had to learn to get things done fast.

Mike Hernandez 38:41

Yeah, right. And I think and I think that’s what contributed to the success of a lot of the people as they were, they were put under this pressure of being able to, to produce feature level quality for TV, TV budget, and a TV timeframe. And of course, we, you know, we tried our best to try to hit that. And I think we did a pretty good job of getting a certain level of quality in there. But of course, it wasn’t feature level quality, but it was pretty good quality at the time. You know, for given the constraints we had given the timeframe we had in the budgets we had we it looked pretty good. It was pretty fantastic. You know, and it was actually really funny and and there was a lot of really funny moments on that show. But again, like I said, I just I got to meet really great people. And I got to learn a lot of valuable art artifacts within within that type of a pipeline. So it helped propel me to other jobs. You know, from there, I got to do art directing on on I became an art director on trek for loved working on that film. You know, I got to start off as production designer on other shows and then some of the shows might be canceled. Then I went on to our directing. Other things are directed some TV specials for DreamWorks. And it’s been like one of the funnest journeys I’ve ever spent working for that studio. They’re fantastic people, they make some of the best work in the industry, if I ever, ever had the chance to work with him again, and it’s the absolute pleasure.

Eric Rhoads 40:11

I had the pleasure of seeing Jeff Katzenberg at the one of the original Ted conferences, where he revealed a little bit of footage from Shrek that they had. They were just I think Shrek was the first film that they did at DreamWorks wasn’t

Mike Hernandez 40:29

Shrek was it? Was it their first film? Gosh, you know, and I think about it. No, Shrek was the first 3d film first neighbor. Yeah. And that was at our PDI facility up in San Mateo. I think San Mateo, up there up there in the Bay Area. You know, we had that that PDI studio that eventually got shut down a few years back. But the PDI studio was basically where we did all of our 3d Films because we didn’t have that kind of facility at the Glendale facility. So yes, that was our first 3d film ever made. But our first ever film, I believe, was Prince of Egypt.

Eric Rhoads 41:07

So let’s move into the world today, you have kind of made a decision to morph into kind of a full time position as an artist. I mean, you were a full time position as an artist, but as a fine artist working on your gallery works now. Is that right?

Mike Hernandez 41:27

Yeah, for sure. And again, I always consider myself you know, having having a foot in both worlds, you know, the entertainment industry and the fine art industry or the contemporary art industry, or the plein air, you know, just a foot in both worlds has proven to be more beneficial for me than I ever imagined. You know, I, I leverage so many things off of both sides. You know, from my cinematic point of view, the things I’ve learned about cinema in animation, and storytelling, and how to be intentional, you know, an economical because we only have seconds sometimes to get people to get the essence of what’s on screen, to sell emotion. and be creative that’s lent itself in so many ways to plein air painting, you know, I think if I never did that, you know, I think I’d be more of a literal type of painter, I’d go out and plan it painted plein air painting, but just try to color match everything and, and not cheat anything and not push the composition too much. But that’s not to say people who don’t work in entertainment industry who are just plein air painters don’t do that. I mean, there’s all kinds of amazing painters in that industry in the planer industry who do that who are cinematic, and they never, they’ve never had a foot in the cinema world, but they just know how to push color and imagination, I just wasn’t one of those people. So I think it was great that I had the leverage of the entertainment field teach me something about storytelling, and how it can, it can lend itself to color to lighting to composition, into, you know, the economy of detail, all of those things. And then vice versa, you know, things I learned from outdoor painting, natural light, all of those things fed themselves into the entertainment industry, you know, I leveraged off of both of those things. So I continue to do that. And for right now. So back in August, I think is when we got to the point where I was finishing up on a show that I was working on, and it was coming to an end. And because of COVID at the time, a lot of a lot of the big names, you know, in the studio, a lot of artists, you know that I respect, I started noticing they were just one by one, they were leaving the studio, and they were headed over to Netflix and Sony and other places. And I was thinking, Okay, this isn’t good. I noticed that there’s a downtrend here and a lot of people are starting to leave and I see the pattern emerging. I get what’s going on because the COVID. And so eventually, I had my views and he said, Look, you know, just a heads up, you know that it looks like you know, we don’t know what’s next for you here, we’re coming to the end of this. But of course, we would love to keep you here we’ve been and we love what you’ve done here, and I love doing what I was doing there. But in essence, they just said, you know, at the moment, if things are getting slim, they’re getting very slim, and a lot of people you know, you’ve seen them go. But they were looking to other, you know, outlets for me, like, you know, maybe you could do something in that painting, maybe you could do this over here and there. And you know, and at the time, you know, we explored some of those things. But ultimately, in the end, it was a good opportunity for me to do something I haven’t done in many, many years, which was to kind of really take some time off. And and focus on family for one, you know, because he dedicate so much. For me, it was always dedicating a whole bunch of time to DreamWorks. And that animation which takes up most of your time as a production designer or an art director, or even just a visual development artist, and also doing my plein air work on the side workshops and events that took up pretty much all of my time. And then I got to think to myself, what about my life? You know, what about my family? What about what I want to do? So I thought maybe that you know, for COVID you know, given the circumstances is probably a good Time to hit the pause button for a little bit, you know, and take some time away from the studio and focus on my own personal work, focus on my health, you know, focus on, you know, relaxing and focus on my personal work. You know, as a plein air artist, I kind of felt like sure with, with all of these things juggled at the same time, I think kind of, you know, move forward as an artist. But if I finally get a chance to take a few months off, and focus on plein air or studio work, that’s going to be great. And it’s been tremendous. It’s been so fantastic. I’ve been able to, you know, now spend hours and hours, you know, painting in the studio or going out and painting on location, and being able to kind of get myself to the other side of things that I wasn’t able to get to the other side of before, such as, you know, the risks that you normally don’t feel comfortable taking in, in studio painting, you know, for an example. How to start painting beyond the photograph, or how to start leveraging some of the things I’ve learned as a plein air painter, when I’m painting from photos, because obviously, with the pandemic, we weren’t going out and we weren’t painting from life as much, you know. So, you know, some of that was happening. But most of the time, I ended up just kind of saying, Well, you know, so much for that trip to Italy, I guess what I’ll do is I’ll just download a picture of Italy from the internet and paint that. But then I guess what I have to do is leverage off of what I’ve learned as a plein air painter, what would I do? You know, what kind of colors what, you know, I know what a photograph does, I know how it flat things and changes the colors. And I know that there’s no high key lighting in it. And I know the composition isn’t sound I know I’m not there to experience what the culture is, and all the things that bleed into it. So it’s forced me in the studio to try to take, you know, take it upon myself to leverage and trust that it’s in there. And then I know that I can pull it out.

Eric Rhoads 46:53

So now you’re climbing El Capitan without a rope. Alright, so, you’ve jumped into it full time, which I think is really exciting. Because it’s gonna be a big change for you. And it’s really gonna be wonderful. You talked about workshops.

Mike Hernandez 47:12

You’re so good at analogies. I love it. The perfect way to explain it. Yes. Yeah, sorry. Go ahead.

Eric Rhoads 47:20

No, so you talked about workshops, you talked about teaching, I learned some things from you. First off a lot of things from you, when you came into to Austin, and you did that, that online workshop that we had, and then you shot these videos on color and composition and so on there, there are things that you touch on and things that you do, that nobody else does. And I don’t mean that in a derogatory sense, it’s it is a depth that just goes beyond what we typically see. And I think that’s because of the rich experience that you’ve had in the cinematic world. And, you know, you talked about a one second frame, but you guys would spend weeks developing that one second frame, you know, develop developing the composition and the color and the light. And I can remember buying books. You know, after films have been released, I went to a lot of animated films when my kids were smaller and, and I would buy the books because the lighting was so different and so spectacular. So what is it that you would say? How can you articulate what you’re teaching differently? When you’re out there teaching workshops? What kinds of things are you focusing on? And can you give us a couple of tips that might be able to be something we can try to apply to our own work? I know, it’s hard to do that with audio instead of showing us.

Mike Hernandez 48:47

Yeah, absolutely. And thank you, by the way you for what you said, That’s quite a compliment coming from you. But yeah, you know, the things I strive for the for, you know, it depends on what kind of, you know, workshop I’m teaching, you know, when it’s only a three day workshop, there’s only highlights, you can give people, you know, in the moment, and you have to kind of figure out how to distill all of the things you want to tell these people and teach them, you know, and break it down and distill it to three days, three days worth of information, and how do you give it to them? And how do you do it without not giving them too much information, because in the beginning of my workshops, it was always too much information, you know, I only had it for three days. So here’s a whole bunch of information. And I learned that some of that is good, but that’s also overwhelming. And especially for people who are maybe beginners and they’re going to get out there. I think what you want to do, and this is how I’ve changed my, you know, it’s evolved is you want to make it simple, you know, make it as simple and approachable, and less intimidating as possible, because in reality, that’s the way it should be. In reality, when you become a seasoned painter, the paintings that have more simplicity in them, and more and are distilled tend to be the ones that we react to the most, you know, and there’s a distilled version And there’s there’s a hierarchy to what’s most important to them. And they’re when they learn to distill, I feel that most people when they get into landscape is that they’re overwhelmed by too much information, and they don’t know where to start. You know, when it comes to the landscape, they’re thinking already the thinking of the details, and all the literal things that are bogging them down and then become a prisoner, to their subject, you know, and they’re binded, to all of the things that they’re holding on to too tight, like the things that we’ve come to things like never paint the things, just paint the broadness of foreign paint the broadness and the simplicity of color, and then find an area where you maybe want to focus a little bit more attention, you know, when you’re painting, but I’ll see beginning artists start off and they’re painting and they’ll start imitating the texture of the tree or trying to paint every brick on the building. And I’m thinking, no, it’s not necessary to have to be so. So tied to the detail, when in fact, less is always going to be more than painting. You know, the more you put into the painting, the less the viewer is going to see. And I had students have a hard time understanding that. And I would explain it to them by saying, Well, look, you know, I’ll give you an example of what I’m talking about. You know, I remember I went to trailside galleries in Scottsdale, I’m sure you’re familiar with them. It was great guy. Yeah. And person I met at DreamWorks, who once came down to do a workshop for us. His name was Bill Anton. I’m sure you know who he is.

Eric Rhoads 51:31

We had him at the Plein Air Convention.

Mike Hernandez 51:34

One of the greats, one of the great he changed so many things for me when he came into DreamWorks to do a demo, because one of our art directors saw him in on I forgot what events they went to the repeating of seascapes from Catalina Island. And they saw him doing the beautiful seascape. Like, nothing, you know, and they’re like, we would you come down and do a demo for us at art center. And I started at art center, DreamWorks. So he came down and he changed so many things for me, because he came in and I was thinking when he was going to do an oil painting of some, you know, he invented a High Sierra landscape with a lake. Very, you know, Edgar Payne, you know, but in his own way, he he painted everything with, like, acrylic brushes, you know. And I was thinking that’s really odd. I thought he used bristle, and he probably does use bristle. But for that particular demo he was doing he was using acrylic brushes, and he changed my approach to oil painting, which was he used a lot of the liquid or liquid, what do you call it? The terpenoid. Yeah, or control time, but gamsol gamble, thank you, because I don’t think that oil that much I forget, began. So he used a lot more. So I look at it, if you guys are familiar with his paintings there, they come off as very, very thick, you know, very textural. But to see him painted and executed, you know, with like a very lean, lean approach in the beginning, by using more gamsol in the beginning and painting it wetter and leaner, it actually allows it to build up more, which is interesting, as opposed to starting off with thick paint, and trying to put more thick on top of thick, it’s almost like trying to put butter on butter, it doesn’t work. And then he just comes in with this beautiful like, palette knife and then just starts messing everything up. That’s what we thought he was in. He’s going in, he’s stumbling all over this thing. But in, in, in fact, he’s just, he’s bringing things together by doing that. So by pulling those colors together, loosening up the edges and having colors kind of skip into other colors, started building a tapestry effect. But, but he he was one of those people that just kind of you know, came in and taught me something. But anyway, I’m getting off the subject. The question was about Trump, I love the story, I was going to tell you about trailside galleries. So I met the trailside galleries, I’m teaching a workshop down there. And I go in and I take my students at lunch break and it was good to go take a look at this gallery. And we walk into trailside and of course there is this you know, you know, all kinds of amazing paintings. There was this one painting from an artist who did this really, you know, from Florida feeling gorgeous painting of the Grand Canyon. And, but that artists use probably like a triple odd brush, you know, to paint every single detail every crevice, every rock from the foreground to the background. Respectfully, it was overwhelmingly you know, like, what it must have taken to do that with just, you know, beyond words, to paint it that detailed, but painted everything, every color, every texture, every rock, and there was a lot to be respected for that painting. It was glorious. It was pretty neat. However, the painting next to it was Bill Anton. And his painting was almost about the same size, but had maybe about 60% 60% less detail in his painting. And it good enough, you know, it’s it was easier to get to what it was Bill and Tom was saying in that painting, it was like boom, more immediate and it really rang home. Like, wow, okay, there is something to the essence of kind of only distilling it down to the most important things, the most important marks and colors, and shapes. So when I teach, it’s always that essence, like guys don’t get, don’t get so pulled into having to paint everything. And don’t paint everything from left to right with the same amount of detail and color. Find an area where it’s most important, you know, don’t do what the camera can do, don’t do what the photograph does, you know, have your hierarchy, what’s the most important area? You know, where do you want your colors to sink a little bit more? Where do you want your contrast? Why did you paint that tree parallel to the other tree? Well, the students will say, well, because it’s there. I said, so you’re letting the landscape dictate what’s right for you, you know, again, get in there. And you become, you know, basically the ambassador to the to the image, you have total control of what’s in front of you. You don’t want that tree there, take it out. Or if you want a bigger put it over here, you know, if, if you like, a brighter highlight on the water or something different, try to do that there, but justify it figure out how it counterbalances in real lighting.

Eric Rhoads 56:08

That’s a hard lesson to learn, to edit.

Mike Hernandez 56:14

It is and it comes from years of mileage, but it also comes from years of taking those risks. So that’s why I tell students look, if you want to get there faster, stay away from all the literal stuff. Don’t get bogged down by those little literal, start painting more broadly, use a giant uncomfortably large brush. That’s rule number one, just a huge brush that you’re not comfortable with using that’ll help you simplify and get rid of the other stuff. Rule number two is paint smaller, study the paint more of them, you know, you’re better off painting, if you have five hours in the day to go out and learn. You’re better off painting, five, one hour study as opposed to one five hour study. Now that’s not the case, we’re an advanced, seasoned painter, you can go out and pick whatever size you’d like you can get it before the beginner, the beginner only has what I call and what I’ve learned over the years of teaching this stuff is the 45 minute window learning period, you’re only going to learn what you’re going to learn for the most part in a given in a given painting 45 minutes to keep it fresh, after 45 minutes, you’re going to lose some of the freshness, you need to change the painting and go on to another one. That’s not to say that there’s going to be times throughout the week, you’re just going to need to stay on one painting for a few hours and just get to the other side of it. But there’s also something to be said about finding a way to to pace yourself and do more smaller paintings, smaller palette, less detail, a larger brush, a smaller timeframe will give you that simplicity. And when you see the simplicity and the broadness, what evolves from that is the ability to edit in is the better ability. You won’t get that from going out there for added for hours and hours painting a giant painting.

Eric Rhoads 57:59

Smaller palette, I assume you mean fewer colors, fewer colors.

Mike Hernandez 58:03

So yes. Yes, more colors can get you into more trouble when you’re a beginner, not when you’re advanced, but as beginner. And you’ll even find that some advanced painters also have a very small palette as well, you know, I tend to kind of I never usually have more than like, you know, 10 colors on the palette. And sometimes I might paint with only four or five colors, you know, and in fact, some of my most favorite paintings like the Edgar Payne’s, you know, that you’ll see in a gallery, those paintings, you look at them, and they’re there’s not that much color in there. They’re sophisticated color, but there’s not a lot, you know, more color does it make a better painting, you know, how you use that color.

Eric Rhoads 58:41

You were talking about mud the other day in the value of mud. And one thing that it’s taken me a while to understand is that some of the most beautiful paintings are all gray, you know, variations of gray, but they’re all gray, and then they have a spot of color in the in the focal point. And, boy, it works and it still makes the whole thing feel like it’s colorful.

Mike Hernandez 59:04

Absolutely. You know, and if you have you got to kind of think of what saturation is, you know, there’s there’s two things to consider full saturation, brings things forward. Always bring things forward. And what is it we’re trying to, we’re trying to achieve in painting, we’re trying to get depth. So how deep can you get when you’re using too much saturation and too much color? You know, not to say that you don’t want to use saturation and color but you know, because you want you want the push and pull of saturation, the saturation warm and cool, right? You know, more detail in the foreground, less detail in the background. All of those things are tricks to giving you depth in a painting. grays are another one of those things that can give you that kind of depth, you know where they kind of be pushed back, you know, into the painting. And then as you saturate colors, or especially if you go warmer that pulls things forward into painting. So you always got that push and pull effect, you know, that’s going on in there, you know and the other I forgot what the other thing principle was, I got lost my thought there. But I think that’s one of the most important, critical aspects for me.

Eric Rhoads 1:00:07

Well, this could go on and on and on. And this is so valuable.

Mike Hernandez 1:00:11

I’m getting locked in my thought.

Eric Rhoads 1:00:12

We’ll have to do this again sometime. Because there’s so much depth here, I’d encourage everybody to pick up your video, which you can find online just by searching your name and video, but there’s two really good ones. And they really go into a lot of depth of this. And I think that would be really terrific. Mike, any final thoughts before we head out?

Mike Hernandez 1:00:34

Yeah, as excited as I am about talking about a lot of these things, I have such a long way to go, you know, a long way to go in learning what I do, especially when I look at the work that I see from my friends on social media and their paintings and tumbling, you know, and that’s one of the most amazing aspects of social media now, as we have access to what everybody’s thinking that day, you know, right at that moment, we get to see what they’re doing. And it’s wonderful to be able to see people like that. And so I’m always inspired. And I’m always inspired by everything that you’re doing, Eric, and the opportunities that you’re giving people by having podcasts like this. And by trying to, do what we’re doing with pace and all of these other things. It’s a big thank you to you for everything that you’re doing to try to keep us on fire. Appreciate.

Eric Rhoads 1:01:23

Well that’s very kind. Mike, thank you so much for being on the plein air podcast.

Mike Hernandez 1:01:28

Oh, thank you for having me, Eric. It’s been a pleasure.

Eric Rhoads 1:01:32

Mike Hernandez is so thoughtful. Thank you, Mike, for what a great interview really has so many good things to say. I think we could have probably talked for hours and maybe we’ll have him back again someday. All right. Got a couple of great videos that Mike Hernandez has created. You can find them at streamlineartvideo.com. Okay, you guys ready for some art marketing ideas.

Announcer 1:01:50

This is the Marketing Minute with Eric Rhoads, author of the number one Amazon bestseller “Make More Money Selling Your Art: Proven Techniques to Turn Your Passion Into Profit.”

Eric Rhoads 1:02:01

And in the marketing minute I answer your art marketing questions yours can become part of the broadcast if you email me, [email protected]. We also have our own art Marketing Podcast. It’s the same content that we just push out as a separate podcast. And so if you don’t want to listen to plein air podcast, which you want the marketing, you can just go there. Now here’s a question from John O’Neill in Albany, New York who says I’m finally ready to start a website and a newsletter. My question is, does it need a catchy title or something that’s more direct? Like my name? Well, John, I think you know, in my book, make more money selling your art or whole a whole thing on websites. And that’s something you want to check out. But first off, everybody says, Well, I have to have a website, well, the web is changing, and things are changing a lot. Now, the question is, before you even create a website, you have to ask yourself, what’s my strategy? Why am I creating a website? What do I have? What do I hope to have happen with that website? Is my website, a branding tool, a way to show my artwork? Is it a way to sell my artwork? Is it all of the above? What is the 80%? Or what is the one thing that you really want to focus on and try to figure that out before you decide if you’re going to start a website, because, quite frankly, nowadays, you can kind of do almost the same thing with Facebook and Instagram. And there’s also a lot of other things that are trending. So you may want to ask yourself, Is this really necessary anymore? Now, there’s a lot of people out there that make great websites, and you know, you can kind of make your own through them. And some of them are art specific, and some of them are not, you’re going to have to decide what works for you. But do you need a catchy title or something that’s more direct? Well, catchy titles can be risky. You know, if you were, remember Thomas Kincade, the painter of light I mean, that was a catchy title. And but yeah, and then for a long time, everybody was the you know, the painter of this and the painter of that, but I’m not so sure it really meant anything. You know, what you what you’ve got to do is figure out what is the focus on what do I really want to spend my time doing? The big mistake that I think artists make when they’re trying to market themselves, they try to be too many things to too many people, they try to do too many styles or they try to do too many subject matter. Figure out first what it is you want. So if you are going to be a catchy title, or if you’re maybe it doesn’t even have to be catchy. It might just be you know, John O’Neill, landscape painter, it might be john O’Neill, ocean painter, seaside painter, or whatever it is, you’re good at, you know something because we can’t all be good at everything and you want to kind of get known for something. So first thing I think is, put your name up there, John O’Neill and then then if you want to say I have a subhead, that is kind of an explainer, you know, a subhead explainer is like Coca Cola and then it’s is the real thing, right? So I don’t know if that means anything anymore. But it did it maybe at one time. So you got to think about that. But no, your name is fine. And people are going to Google your name and you want them to find you. And this is an opportunity to brand yourself. Now one mistake I think a lot of people make is they love they fall in love with their signature, and they put this big, unreadable signature at the top of their website. Now, that’s okay. That’s okay. If you also put your name on top of it in text that somebody can read. But a lot of people can’t read that stuff. Everybody thinks they can. And you know, there’s nothing worse than a signature that nobody could read, at least put your name on the back of the painting, too. We’ll have a whole nother thing on the back of the painting sometime. Anyway. Hope that helps.

Eric Rhoads 1:05:45

Here’s a question from Jeffrey Skelton in Nashville, Tennessee, who says I’m always hearing about new scams. Are there any traps that artists can be aware of and avoid? Well, Jeffrey, I’m not the guy. You know, this is a marketing podcast. But let me just tell you what I know. And I don’t know much. But I have been approached many times. from someone, it’s always a different name. It’s always a different email. But the email goes something like this. I was looking at your website, I’m trying to find something really special for my wife for her birthday, or anniversary, you know, some some particular thing. And I found a particular painting, I’d like to buy it from you. Can we make arrangements? And so here’s how the scam I’m told works. And that is that, you know, they they say they want to send you a check. And then you send them the painting, and then the check doesn’t clear. So first off, if they’re saying those words, chances are it’s a scam. But secondly, you know, you can hammer the cheque, you can go to the bank, and you can say, I’m not going to send this until the check clears. Now one of the other things they do is they, they overpay. So let’s say your painting is $1,000 they send you a 15 $100. And then they sent you know, they send the check and then they overpay and then there’s some way that they cancel the check and they manipulate it or something. And as a result, they’re getting $500 cash out of that transaction when they had no intent of paying. If you want to read up on art scams, I would probably check out I think the FBI has a an art scamming division. You might want to check that out. But you know, something sounds too good to be true. It is it always is. So just keep that in mind.

Announcer 1:07:37

This has been a marketing minute with Eric Rhoads. You can learn more at artmarketing.com.

Eric Rhoads 1:07:45

Well, a reminder to sign up for pleinairlive.com. And since we’re not having the convention this year, this is your time. And you know, we make it pretty entertaining, we have a lot of fun. And we have a gathering of artists for a very reasonable price. And it’s amazing. And if you can’t make the dates, you can watch the replays. There’s different links of different dates on replays. And so you can do that. Also make sure that you get signed up and get your entries in your best paintings for the year for the past 10 years. It doesn’t matter. register at pleinairsalon.com. But get it done by March 15. Two big awards are coming on plein air live, we’re also going to do a lifetime achievement award on plein air live for artist Joe Anna Arnett. So if you’ve not seen my blog, where I talk about life and art and other things, it’s called Sunday coffee and you can find it for free at coffeewitheric.com and then subscribe to it so that you get it all the time. Well, it’s always fun to do this. We’ll do it again sometime like next week. We’ll see you then I’m Eric Rhoads, the publisher and the founder of plein air magazine. You can find us online at outdoorpainter.com. Thanks for listening today. And I hope you have a terrific day. Remember, it’s a big world out there. Go paint it. We’ll see you. Bye bye.

Announcer:

This has been the plein air podcast with Plein Air Magazine’s Eric Rhoads. You can help spread the word about plein air painting by sharing this podcast with your friends. And you can leave a review or subscribe on iTunes. So it comes to you every week. And you can even reach Eric by email [email protected]. Be sure to pick up our free ebook 240 plein air painting tips by some of America’s top painters. It’s free at pleinairtips.com. Tune in next week for more great interviews. Thanks for listening.

- Click here to subscribe to the free newsletter, Plein Air Today

- And click here to subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue!