Master these atmospheric perspective elements to give your paintings a powerful sense of depth.

By Kathleen B. Hudson

Kathleen is featured in the PaintTube.TV workshop Creating Dramatic Atmosphere in Landscapes

The more you know about how atmosphere affects your view of a landscape, the more you’ll be able to see those effects when you’re looking at a landscape (even when they’re subtle), and then give your painting depth by painting them with intention. Atmospheric perspective in painting refers to the increasing effect of the dominant atmosphere in a scene upon objects as they recede into the distance.

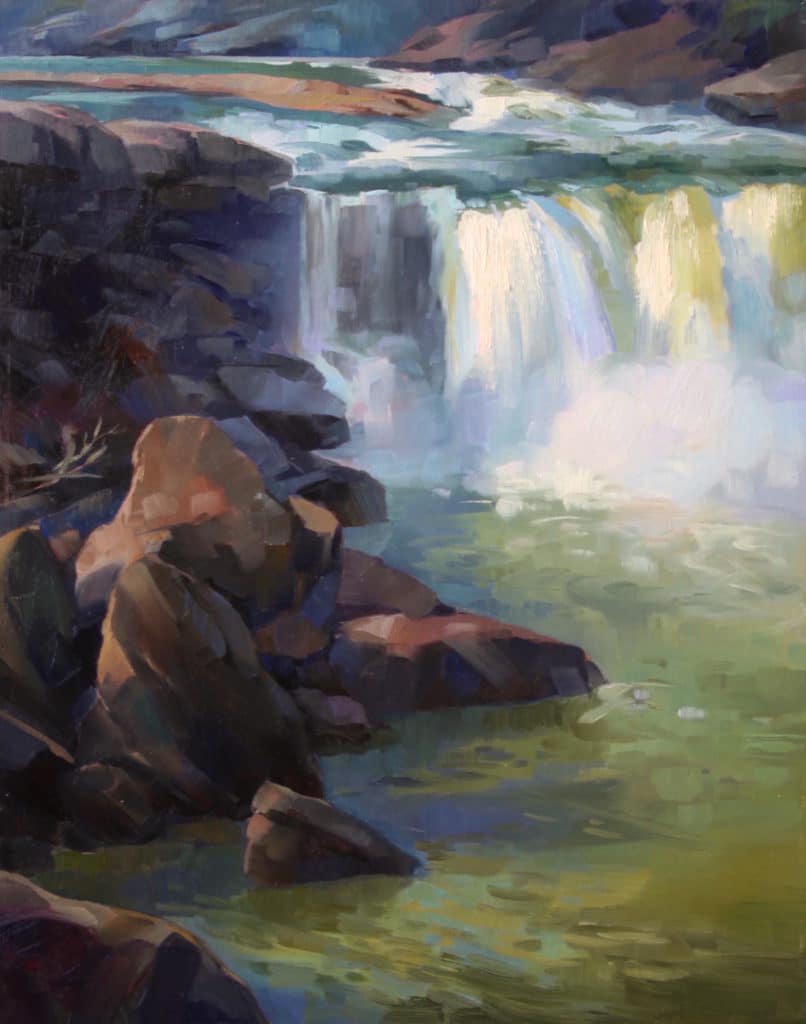

Artists can create a sense of atmospheric perspective in a landscape using several visual tools: value, color chroma and temperature, edges, and texture. The first and most significant is value. As objects recede, more atmospheric haze lies between the viewer and the subject, and so shadows look noticeably lighter. Light patterns look different, too — they’re lower in contrast and sometimes lighter depending on the atmospheric conditions and light source. Value is the most significant part of creating atmosphere in a landscape because even a sketch or grayscale painting can read as heavily atmospheric if the value shifts make distant objects recede.

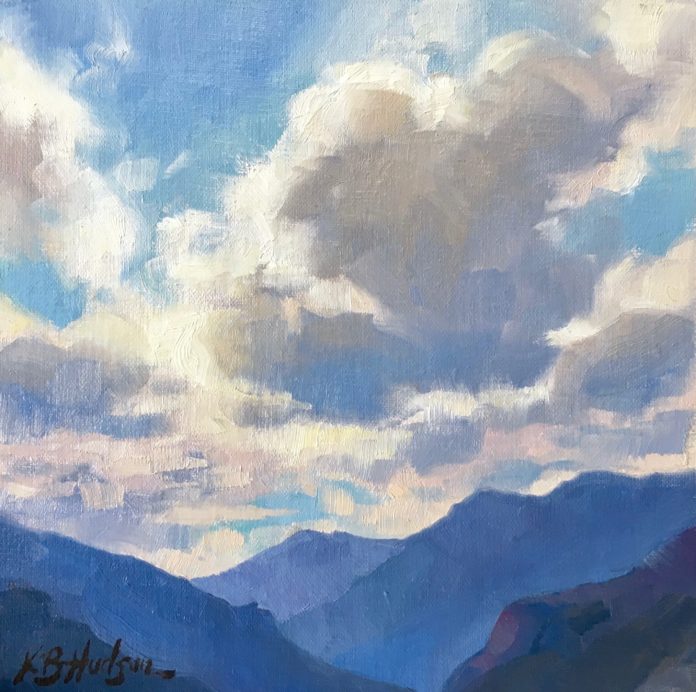

The second thing that shifts with atmospheric perspective is color: its chroma and temperature. In some conditions, atmospheric haze makes the temperature of the landscape cooler, or bluer, as it recedes. In a forested, lower-pollution area on a clear or slightly hazy day, you’ll see receding mountains take on a lighter, bright blue cast the further away they are. This is because trees and other vegetation emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs) along with oxygen as they breathe, and VOCs create a vapor that scatters blue light from the sky.

But the receding landscape isn’t always a cool, blue temperature. That depends on the time of day and the position of the light source. During a sunset or sunrise, fog and vapor reflect the light of the sky the same way — which means they’ll take on more of whatever the dominant sky color happens to be at a given moment.

Under more polluted conditions that are nearer to cities, the parts of the landscape that are further away are often lower in chroma (grayer) than the foreground, where you’ll see brighter color along with more contrast. This is because pollution particles absorb light rather than reflecting it like VOCs do. The lower chroma rule of thumb can also be true of dense fog and overcast conditions — when light is blocked, local color is clearer in the foreground, but gets obscured more with distance.

Consider Edges and Texture for Atmospheric Perspective

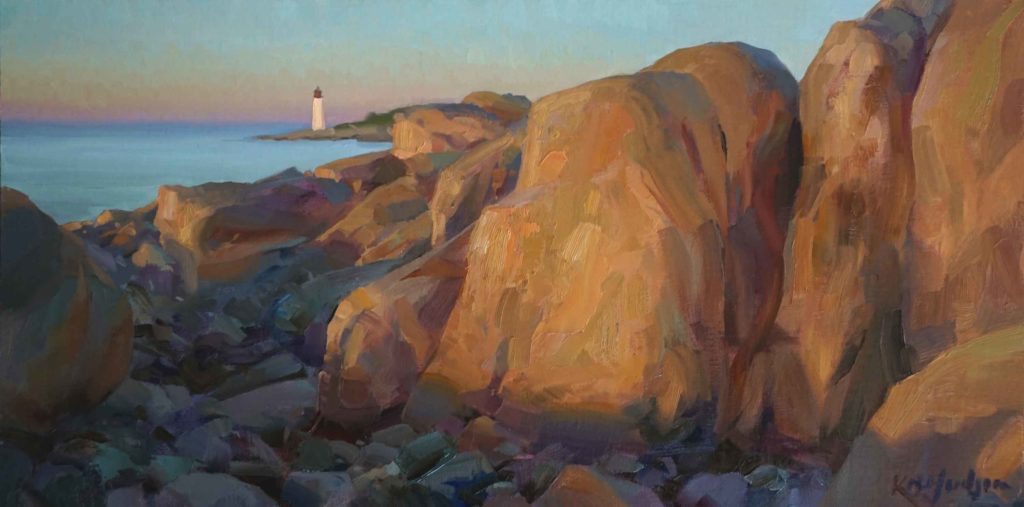

The final ways of giving your painting greater atmospheric depth is to consider your edges and texture. Edges get softer as they become more obscured by haze in the distance. You can play this up in your work — soften the horizon, for instance, even if you see a harsher line when you look at it. (I even do this in seascapes where I see a clear line on the horizon because a softer edge makes the horizon recede.) You can soften the edges of trees and other landscape features and flatten their shapes as they retreat into the distance.

Texture, too, is a useful means of creating depth. More texture in the foreground will bring it closer to the viewer; it’s also a great way to create interest in a foreground without shifting the values so much that they detract from the focal area. Just as edges grow softer with distance, a smoother or thinner texture for distant objects increases the depth of a landscape.

If you master these visual tools, you’ll be able to give your paintings a powerful sense of atmospheric depth. But remember that a specific landscape’s atmosphere can’t be boiled down to rules — so observe the value and color shifts closely when you sketch and paint from life. Color temperature and chroma shifts are especially dependent on light, weather conditions, and the time of day. These will change from place to place and season to season.

Note that these subtle shifts are exactly what a camera struggles most to capture, so this is where your knowledge and observation will especially come to your aid in the studio. The habits of observing, taking notes, and painting on location will help you recall the unique character of a landscape’s atmosphere.

And better yet, practicing these things often will move you to become a true student of the landscape: as you refine your powers of observation, you’ll grow in your sense of wonder — and your paintings will certainly tell that story.

About the author: Kathleen B. Hudson is a nationally recognized artist from Lexington, KY and is featured in the PaintTube.TV instructional video “Creating Dramatic Atmosphere in Landscapes”. Her painting “Bright Morning, Timberline Falls” won Grand Prize in the 2019 Plein Air Salon.

Like this? Click here to subscribe to Plein Air Today,

from the publishers of Plein Air Magazine.

[…] Things further away look greyer (less saturated), and less contrasted. This is because of the atmosphere between our eye and the further objects. Look at the example below Pierre-Auguste […]