BY DAN MONDLOCH

I come from the world of watercolor art—the societies, the magazines, the books. I love it, in big part because my dad is a watercolorist. In college I was exposed to and still have a great appreciation for contemporary art, but the last couple of years I’ve been bitten by another bug: plein air. A growing number of artists embrace the genre, yet others are skeptical. Why do some gravitate toward painting outside while others say, “Why bother with the hassle?”

So, what’s the big deal with plein air?

When I think of plein air, a romantic vision comes to mind. The day starts with a short walk from my hotel to a bakery where a fresh chocolate Bismarck and coffee await. I grab a seat outside under an umbrella to nibble and savor every morsel; contemplating the beauty of the rainy scene before me.

Then suddenly the clouds begin to part, the sky opens up, and the most amazing light illuminates the world around me. The horizon glows, people start to stir, and every intricate feature of the surrounding architecture is bathed in the most remarkable light. Everything comes alive. I quickly set up my easel and knock out a stunner in mere minutes, and to top it off a local businessman at the table next to me purchases the painting and is interested in seeing the others from my creative excursion.

A nice indulgence, and arguably it goes a bit too far at the end, yet there is some truth to the emotion the story evokes. However, the other side of the plein air coin is a bit less optimistic. . .

It’s late morning, I’m running behind. My son should have been to daycare an hour ago and I still haven’t had a cup of coffee. Dirty dishes fill the sink and more than one load of laundry is waiting to be started, but that’ll have to wait because I promised myself no matter what I am going painting today.

After loading and unloading all my gear, I wander around for 45 minutes trying to find that perfect spot I saw one time while driving—a spot that has now seemingly vanished off the face of the earth. Slightly irked, I settle on a quiet spot off the walking path next to a calming cattail pond. I forgot my viewfinder, suddenly the mosquitos are feasting on my legs, and now it feels like the sun is burning a hole through the top of my head.

A passerby stops to ask what my real job is, and when I turn to respond I bump my easel and my painting falls face-first in the dirt. Before cursing and chucking half my stuff in the water I utter something along the lines of never doing this again. And you thought it only happened to golfers.

Plein air is a simple and direct process offering honest answers to those questions. Even if the motivation for a piece can’t be articulated with words, the prominence of the subject–for both painter and viewer–causes the motivation to be felt. Audiences expand when you’re working in public; in fact, unless you set up shop in the middle of the woods, you can pretty much bet someone will find you and strike up a conversation. It’s almost as though people feel obligated to engage with you.

To the question of relevance, rarely has an audience for a painting felt more appropriate to me than during plein air painting—it’s art viewing based on a shared experience of the moment. In fact, the question of “Why did you paint this?” seldom even comes up, because they’ve seen what you’ve seen, they see what you’ve created, and the “why” is in the difference between the two. It often doesn’t need to be explained because it can be seen and felt.

OK, so that all sounds fine and makes sense, but doesn’t it also still sound like a real pain in the ass to drag the studio outside and deal with the bugs and sun and weather just to make a painting that you could have done in the studio from a photograph? So what is it about plein air that is so intriguing?

In my experience, not only do I prefer it, but I find it somewhat addicting. Maybe it’s because my studio is in a dark basement room with one small window that no longer opens. Perhaps working from home has me longing for fresh air. If I’m being honest, during the warmer months in Minnesota I strongly dislike being inside. It just doesn’t feel right to me; it goes against my nature.

I grew up biking, fishing and playing soccer all summer, and then after high school I painted houses for nearly a decade. That was my favorite part of that job—being outside, knowing what the weather was doing, being present in the time of year and the cycle of the seasons. Being shut inside writing grants and responding to emails makes me feel detached, and if it goes on too long, I get a bit aggravated and stir crazy! It’s actually embarrassing to admit that, but now only after putting it down on paper do I realize how true it is.

My point is it’s nice to be outside in the fresh air and staying physically active. Bugs, sun, and bystanders are problems that can be easy excuses to not paint outdoors, and they certainly are legitimate, but they can also be easily solved if your heart is in painting outdoors.

Critics might say plein air has been done before, particularly by Monet and the impressionists over 150 years ago; therefore the world simply doesn’t need it—especially not when an app on your phone can turn a photograph into a watercolor or pastel with the touch of a button. But we don’t paint to duplicate and translate reality; we paint to harness human experience—that intangible individual expression of what it feels like to be alive in this place and time.

The cell phone app-generated image will probably mean about as much to someone as the original photograph—likely to be described as “pretty cool” and quickly forgotten about. But for some reason a hand-painted image of that same experience holds a special significance and value to the beholder—it becomes a treasured belonging. Coupled with the experience of seeing it painted in person, you have yourself a precious object.

It’s tough for us to pinpoint and describe why a physical painting of something holds a special significance, but it universally does, and for lack of better reasoning I will describe it as the human element. That human element is often at the forefront of the experience of plein air painting.

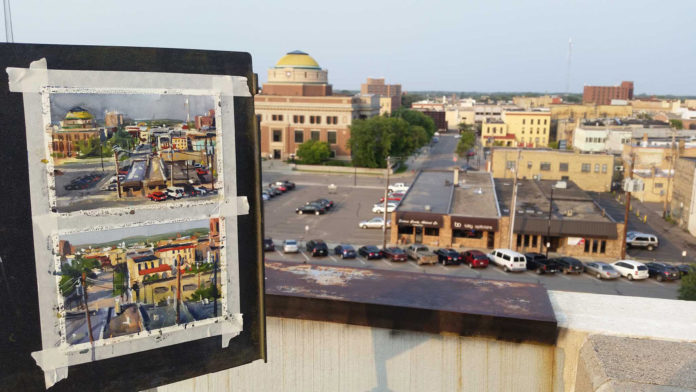

Painted during Grand Marais Plein Air. It’s fun to be both a par-ticipant and an observer when plein air painting, and often times the energy of the experience finds its way into the work itself.

Plein air is pure. You show up with your tools and let the world filter through you. Unaware, possessed; channeling the moment. It turns out or it doesn’t. It’s a couple hour painting; there are no expectations for it to be anything more than that. For that reason they are often referred to as studies for larger studio pieces.

I don’t see anything wrong with looking at them that way. Perhaps plein air’s greatest weakness is that it will probably never be accused of being a deep, thoughtful work of art. But for me that weakness is also its greatest asset. It’s unassuming and direct. A straightforward and honest response; what you see is what you get—attributes to be valued in both art and people.

Connect with Dan Mondloch:

Website | Instagram

> Click here to subscribe to the free newsletter, Plein Air Today

> And click here to subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue!

> Looking ahead, join us in January 2021 for Watercolor Live!

What wonderful feelings I got from reading this article on your plein aire paintings! I loved it! It made me feel like I was a spectator right there with you! I want to start painting outdoors so bad and just have not taken the time . I am old and retired and I need to get started on my bucket list! I loved your paintings! My favorite is the young people enjoying seeing themselves in your painting! How great is that! thanks for sharing and hope I read more of your articles!