I am fortunate to have been given, several years ago, some 50- to 70-year-old art magazines. Browsing through one of them recently, I came across an article about direct painting, meaning paintings created directly from life or nature. Considering the current fascination with, and gushing acceptance of, all things done en plein air, the writer of the article brings a little sanity to the topic. A painting done from life or en plein air is not superior to other works simply because it was done directly from the subject.

What is direct painting? Direct painting is a painting almost always done from life…from direct observation…and typically in one painting session.

The author, whose name is unknown to me, brings a strong cup of coffee to those who are drunkenly obsessed with all things plein air. I believe you’ll find his comments not only worth noting but also helpful: “Direct painting, when practiced by an expert, gives wonderful results; it also imposes stringent rules upon those who practice it. An error of judgement may, probably will, ruin the whole work. For this reason, much knowledge must back up the brush.”

The author goes on to share important factors to help us create meaningful paintings en plein air, including the power of visualization, color concepts, drawing skills, consideration of each object in the painting (and whether it belongs there), and knowledge of masses, tone, and design.

“Nature shows her precious moods for short periods, and only the artist who understands those moods can seize upon them and put them down in paint, with certainty,” he says. “That glorious period, for example, when the world is flooded with gold, just before the sun begins to set, must be understood to be painted; the artist must have observed this effect often before ever he can paint it in the time nature provides. The mind must be stored with those observations so that, when a scene presents itself opportunely under such conditions, he can set to work, backed up with the information provided by earlier study.

“The beauty of the subject relies not upon detailed delineation of the objects in the scene, but on the effect of a certain light upon them; hence, direct work must seize upon the object, arrangement, and effects of light, but mainly upon the last two. Nature will not allow the artist sufficient time to draw everything perfectly; indeed, if it did, detail would be so intricate that it would surely kill the fresh, pure effect the artist desires to incorporate in his work.”

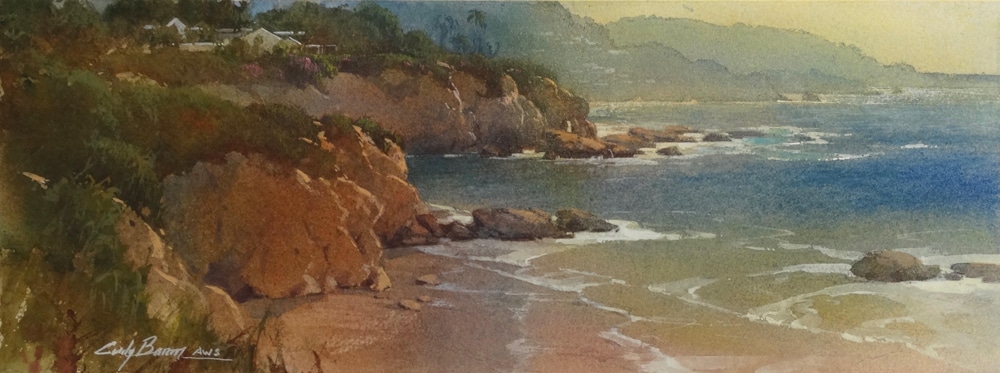

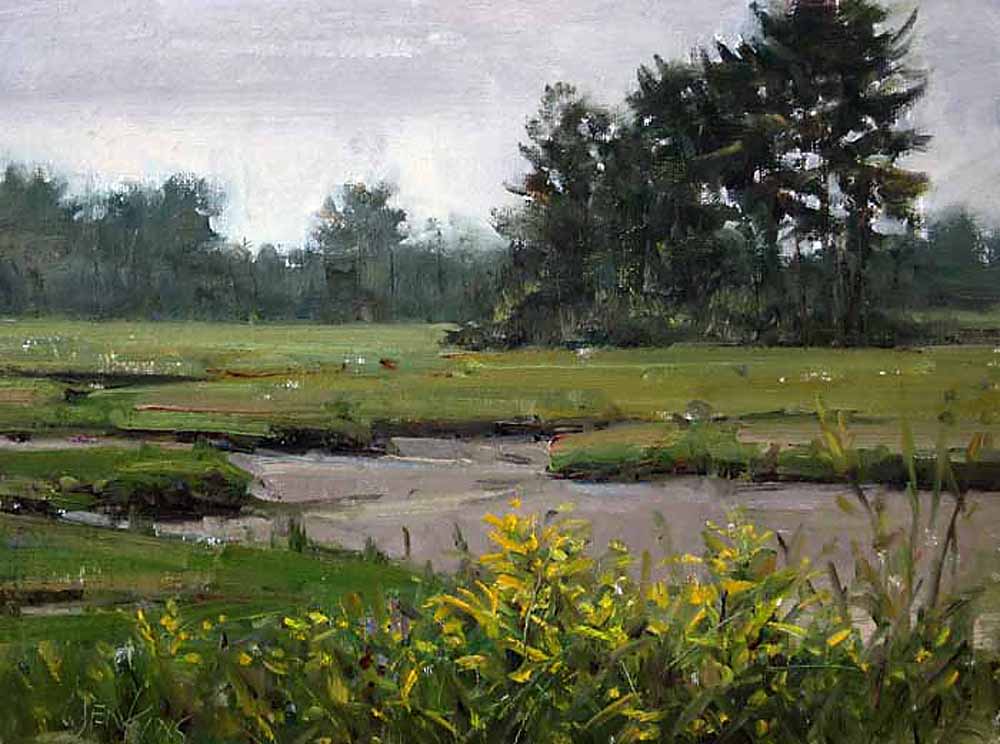

I have great admiration for the work of the guest artists represented here; they each possess the knowledge required to do exceptional work, and because of that, have attained the freedom to express their unique vision. All the works shown were done en plein air.

How does one become an accomplished landscape painter without direct study of nature? The simple answer . . . you don’t. Painting and sketching directly from nature, and spending time just observing, are probably the most important habits of the landscape painter.

Here are additional benefits of creating paintings or studies when working directly from nature:

1) Plein air paintings and studies are a perpetual record of where you’ve been, what you’ve directly observed, and what can always be referenced when needed. They also help recall the moment they were painted, and all the circumstances involved.

2) Direct observation becomes more deeply ingrained and remembered.

3) They create a deeper learning experience because more time is spent observing and attempting to faithfully represent the subject.

4) Compared to working from photos, more senses are involved; not only sight, but also sound, smell, and touch. Even with improved photo technology, the eyes still can discern subtleties that the camera cannot.

5) They provide a direct interaction with the subject; it’s like speaking to someone face-to-face versus reading something someone else wrote about them.

The next step is yours: Assemble your painting equipment, head outside, set up, and get after it. Your efforts, over time, will be well rewarded.

***

Never has there been an instructional video or book that teaches a color system that is so effective that it can completely change the way you paint. You can create any mood, harmony, or flow in your artwork by using John’s color system.

Never has there been an instructional video or book that teaches a color system that is so effective that it can completely change the way you paint. You can create any mood, harmony, or flow in your artwork by using John’s color system.

The best part is that you can do all of this with just 3 colors + white. Even though you’ll be working with a limited palette, you’ll be painting with unlimited color. LEARN MORE ABOUT PAINTING WITH A LIMITED PALETTE WITH THIS SPECIAL OFFER.