Painting Landscapes > Before laying paint to canvas, it’s a good idea to assess your subject in terms of pure abstraction. John Hughes explains.

Understanding Your Subject as an Abstract Design

Before laying paint to canvas when painting landscapes, it’s a good idea to take a moment and assess the scene before you in terms of pure abstraction. Approaching the intricacies of nature in this way will help you to succeed in capturing a visual reality in a purely artistic fashion.

One of the many challenges a landscape painter faces is arranging all of the varied details of a scene into a simplified design that also conveys a sense of reality. This is why “artists see things differently,” as some would say. The artist is able to distill the complexities of a busy scene into something that may be used as the basis of a painted work, through the lens of artistic selection.

Seasoned artists understand that artistic depiction is not just producing a mere copy of what is in front of them, because the kind of art that involves the emotions is more concerned with interpretation than reproduction. If the ultimate aim of landscape painting was to come up with a faithful rendition of nature, photorealism or even photographs would hold the final say, and that would be that! Fortunately, that is not the case!

This is not a new idea — many have expressed it in different ways before me — but it’s worth revisiting nonetheless. This is why I say that art is to the visual world, what poetry is to the written one. In art, the literal gives meaning to the abstract, but the abstract lends beauty to the literal; together the two transcend what could have been accomplished alone.

In the following photographs I have illustrated simplified designs by using a series of small thumbnail sketches to depict the schematic idea associated with each one. This schematic stage is a quick arrangement of lights and darks, or lights, darks, and mid-tones, which form the basis of how the artist sees the underlying design. These sketches should be no larger than an inch or two on any side, and are best executed rapidly with no thought of finesse.

Painting Landscapes

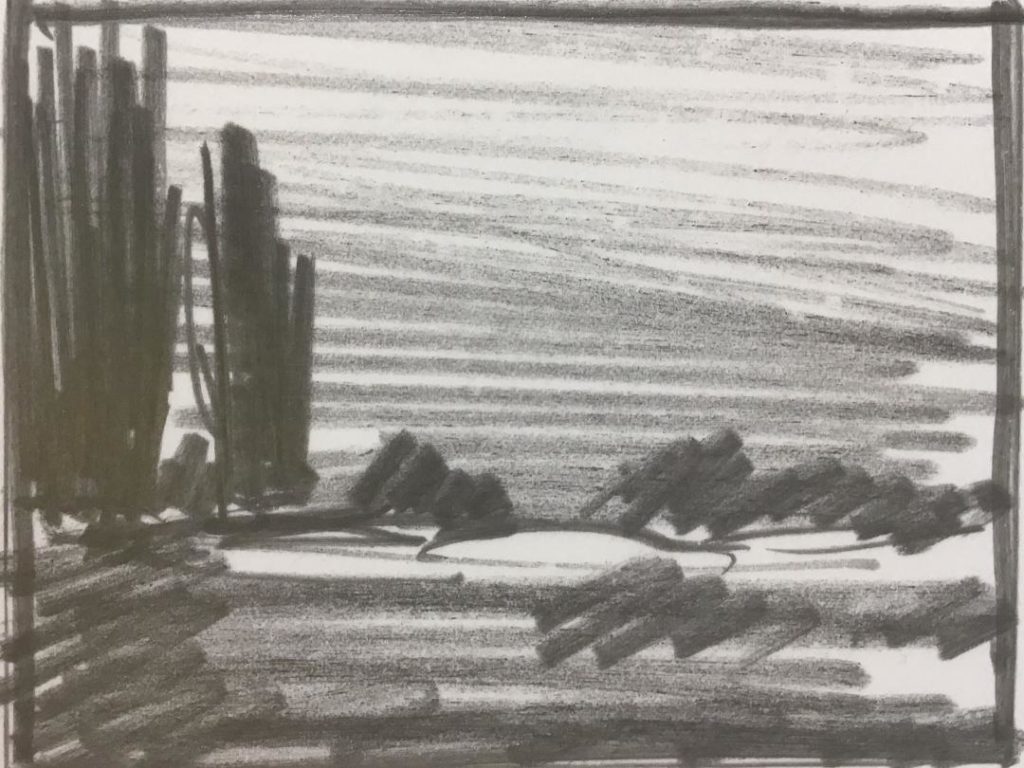

Subject number one is a small bridge in a canal road near where I live. The scene is simple and has a lot of design possibilities for a painting.

The thumbnail sketch for this scene is a flat, poster-like, black-and-white plan of attack. While some adjustments will have to be made regarding division of space before proceeding on to the painting, one can get a sense of how these little thumbnail sketches can be of great help in identifying design problems before they make their way onto the canvas.

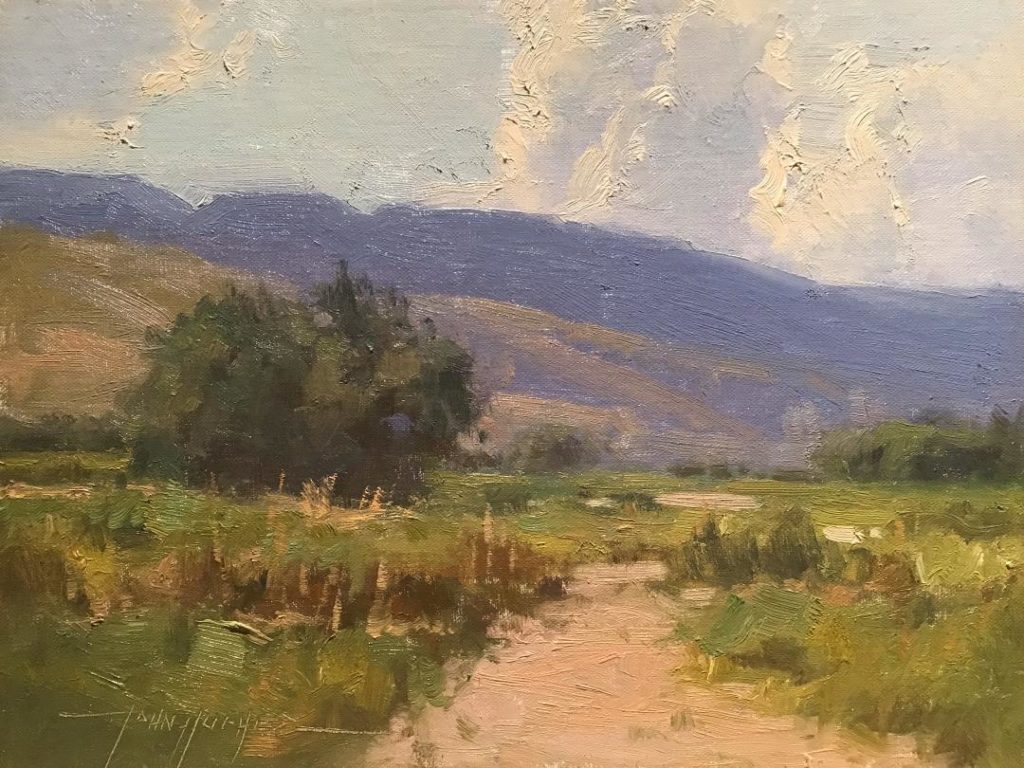

Subject number two is a small 6 x 8 field study I did several years ago. This scene was simple and based on an L compositional type.

The schematic thumbnail sketch is rendered in light, dark, and mid-tone areas, which depict the simple plan of this field study. No frills here, but it is worth noting that the light area in the foreground is vitally important, due to its completion of the value range of the painting, which lends contrast along with reddish tones to complement all of the greens. Notice also in the study how these same tones find echoes of similar, but more muted, colors in the middle distance.

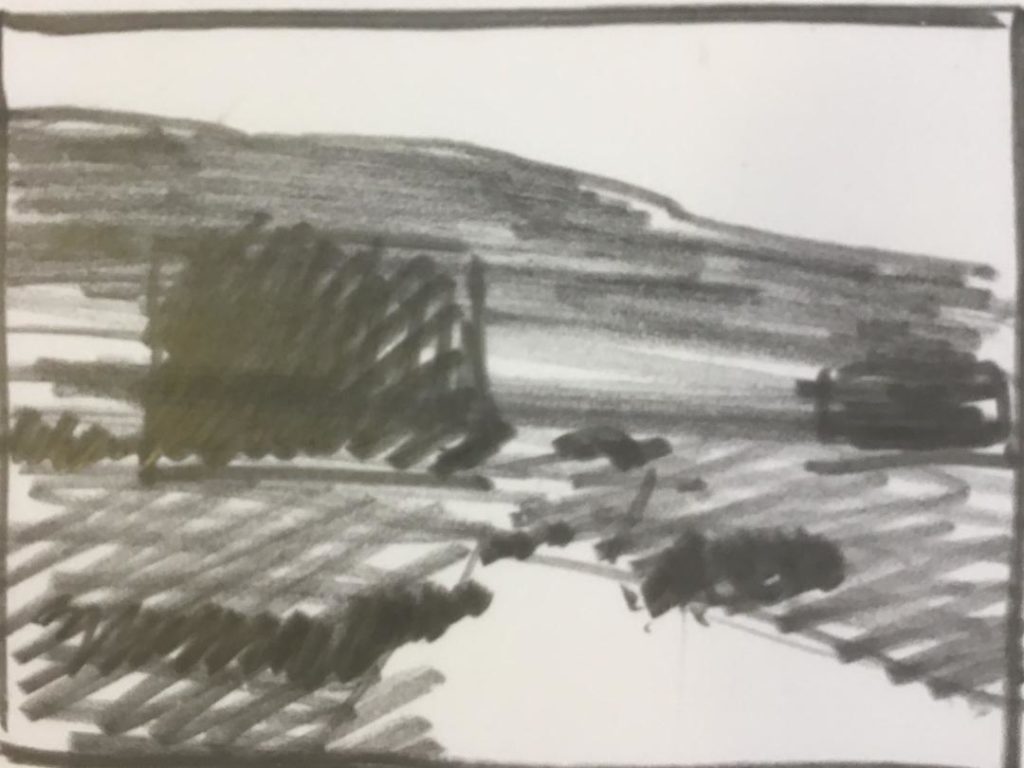

Another field study, which features a Steelyard design along with figure 8s or the compound S idea, which snake the viewer’s eye into the picture. See Edgar Payne’s seminal work “Composition of Outdoor Painting” for further information on “compositional stems.”

Here you can see the basic plan with no embellishments, just light, dark, and mid-tone value areas that serve as the underlying structure of the field study above.

In this last example, I have included a field study I did up Big Cottonwood Canyon last winter. This design features a fairly simple light and dark pattern, which is built on a diagonal theme.

The schematic is nothing more than a light–dark pattern done in two shades. When moving on to the canvas, this idea kept me from veering off too far afield with unnecessary details and sub-shapes that would destroy the simplicity of this design.

I hope this finds you well and ready to go out into nature to tackle the complexities of rural scenery, with a new understanding of what it takes to simplify an often busy scene.

Until next time,

John

Do you create thumbnail sketches when painting landscapes? How do they help you with your landscape painting compositions?

Upcoming travel and art events with Streamline Publishing:

> Click here to subscribe to the free newsletter, Plein Air Today

> And click here to subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue!

You are right on concerning abstraction- I spent several years working non objectively before returning to working from life-nature and portraits. and I had my students working abstractly for a time…. John K.

Thanks for your comment and insight on this subject John!