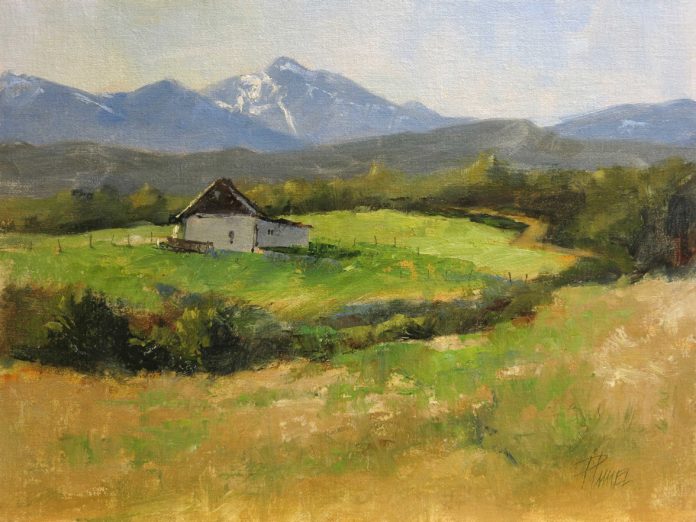

On painting landscapes > The best plein air pieces start with a plan, says Peggy Immel. Follow these tips before starting your next painting.

Painting Outdoors? Plan for Spontaneity!

By Peggy Immel

Painting landscapes is an exciting pursuit . . . especially when painting outside. It’s so easy to become enthralled with the view, the colors, the sounds, and the smells, that the reason you started a painting in the first place gets forgotten. Yet it’s exactly these experiences that make plein air painting the magical adventure it is.

Studio landscape painters are often more vulnerable than seasoned outdoor painters to nature’s chaotic environment, and can be stymied about how to even start a plein air painting. Stories abound about folks who haul their monster easels and supplies out into their yards and paint for days on one tiny painting only to be disappointed with the results. Plein air painting requires a mindset somewhat akin to that of a bareback bronc rider. The best plein air pieces start with a well-thought-out plan that is then executed spontaneously with an intuitive hand. Working for hours on a plein air piece is a formula to kill it. All freshness disappears.

The challenges for anyone painting from life outside are many. The first predicament, and it is a big one, is shrinking the whole, magnificent outdoors into a limited view that will fit onto a small canvas. Next comes the sun. It’s moving! And the shadows that follow it are moving too. Anyone who paints en plein air has had the experience of chasing the light. The sun appears to rush across the sky to the horizon and carry with it the shadows that were a major part of your composition.

Incoming rain in the distance, bugs that have decided you are easy prey, wind that keeps gusting and trying to tip over your easel, onlookers’ questions, a hungry growling stomach — these things, and more, are part of the experience of painting outside. And through it all you must remember, “What was it that attracted me to the subject of the painting in the first place?” “What is my painting about?” Outside of developing tunnel vision, my recommendation to combat these distractions is to have a plan.

1. Do a walkaround.

I start every plein air painting by walking around with my handy viewfinder. A viewfinder can be anything from a rectangular hole that you cut into a piece of paper, to the ritzy adjustable versions you can buy. I carefully study the value patterns and different compositions of a subject.

If I don’t have a viewfinder with me, I will use my camera as a viewfinder. I don’t take pictures while I’m viewfinding; I simply look, turn around 360 degrees several times, and contemplate what my approach to a given subject might be.

If I don’t have either a viewfinder or my camera, I use my pointer finger and thumb on each hand to make a rectangle to look through.

The main thing is to thoughtfully consider the composition and the value pattern of a potential subject. Doing the walkaround and looking through a viewfinder is the secret to figuring out what to include and what to exclude from your painting. It’s not necessary or even desirable to paint everything you see.

2. Write down what your landscape painting is about. “What’s your point?”

Once I’ve decided what to paint, the “What’s your point?” refrain starts. It’s repetitious, a chant akin to that thing called an ear worm, when you can’t get a song out of your head. My first act after my walkaround is to get out my sketchbook and write down the reason for my painting. It might be an emotional feeling, the look of the light, the center of interest, or a title I’ve just thought of.

It’s anything that describes what I’m trying to say. Sometimes I write a haiku. It’s my answer to the question, “What’s your point?” And when I’m struggling with a painting and it isn’t working, the first question I ask myself is, “What’s your point?”

3: Make a composition plan for your landscape painting with value sketches.

Next come the sketches and value studies. I do two or three very small 1 x 2-inch black and white value studies using three values for each study. These simple little studies help me to figure out what the pattern of values and shapes in my painting will be.

These thumbnails are similar to Notans, a Japanese term describing the design of dark and light shapes in art. But instead of being black and white like a Notan, they are black, gray, and white.

Then, following the pattern plan I’ve chosen from my preliminary studies, I do a more traditional 3 x 4-inch value sketch that contains a wider range of values. It indicates key information in the scene, such as where the sun is located, the shadow pattern, and other details that are important to the painting.

These value studies, along with possible titles and “points” scribbled in the margins of my sketchbook, become the map that guides me through the landscape painting process.

It takes anywhere from 15 to 30 minutes to do my walkaround and value studies. And I confess there are times that I want to skip right to the painting itself. Because that’s the fun part, the reason I’m standing outside, paint brush in hand. But I find that the discipline of doing preliminary planning is well worth it.

I refer to my value studies and notes as I paint. My hope is that the end result of this planning is a fresh, vibrant painting that isn’t overworked and looks like it wasn’t labored over at all.

Quotes for Artists

I’d love to take credit for discovering that planning pays off. But I can’t. Practicing something and doing preliminary work with the goal of making it look effortless has been preached by artists throughout history. Keep scrolling for some quotes for your amusement and reflection.

“You must plan to be spontaneous.” ~David Hockney

“Usually it’s a pretty calculated, sustained, and slow process by which you develop something. The effect can be one of spontaneity, but that’s part of the artistry.” ~Richard Estes

“No art was ever less spontaneous than mine. What I do is the result of reflection and the study of the great masters. Of inspiration, spontaneity and temperament I know nothing.” ~Edgar Degas

“Do not be afraid that too much labour over the composition is going to kill the spontaneity. Those who absorb and digest their experiences are, of a sudden, mountains of strength and can produce pictures with spontaneous start and finish.” ~John F. Carlson

“In order to be totally spontaneous, you can’t be too obsessed with accuracy, but if you’re inaccurate in a drawing, it will look fake, and when you act, it will sound fake. You have to find miraculously some proper balance between the two, but there’s no formula.” ~Peter Falk

Aha! The secret to spontaneity is planning.

About the Author:

Peggy Immel (https://peggyimmel.com/) is a Master Signature Member of Plein Air Painters of New Mexico, as well as a Signature Member of Plein Air Artists Colorado, a Member of Rocky Mountain Plein Air Painters, and an Artist Member of Laguna Plein Air Painters Association. She also belongs to the Outdoor Painters Society, the National Society of Painters in Casein and Acrylic, Oil Painters of America, and the California Art Club.

Visit EricRhoads.com to find out all the amazing opportunities for artists through Streamline Publishing, including:

– Online art conferences such as Plein Air Live

– New video workshops for artists

– Incredible art retreats

– Educational and fun art conventions, and much more.

> Subscribe to Plein Air Today, a free newsletter for artists

> Subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue

Without any sarcasm intended I have often wondered what is the point of en plein air painting as opposed to taking a photograph and painting that or a part of that later? I have heard plein air painters say that you cannot compare en plein air painting to anything else but although I do not have a sophisticated eye I don’t think I can tell plein air from painting in a studio.