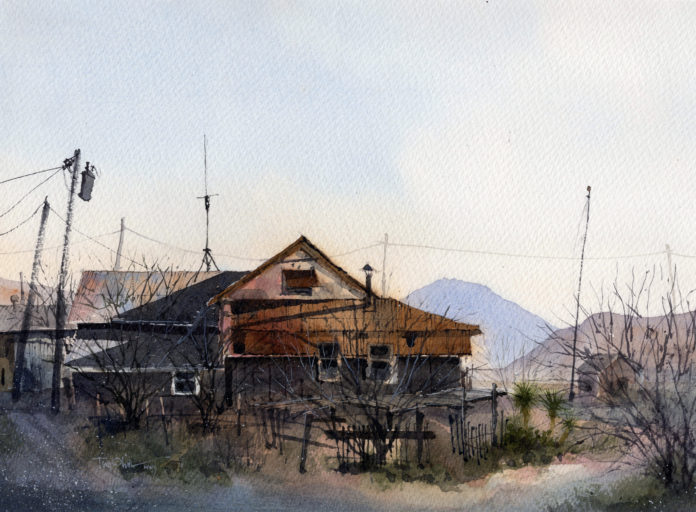

Drawn to rural, gritty, and seemingly mundane subjects, Tim Oliver loves the authenticity, immediacy, and raw honesty of painting watercolors en plein air.

Watercolors with a Western Flair

First introduced to watercolor by a friend in college, Tim Oliver fell in love with the transparency and color-blending qualities of the medium. A landscape architect by trade, he also has a reputation as a top-notch plein air watercolor painter, describing his style as “sloppy representationalism.”

Based in Lubbock, Texas, Oliver recently took some time out of his busy workday (a storm had hit near one of his landscape jobs in Amarillo, and he was on his way to check on his team and the project) to talk to me about the sketchy quality of his work, what draws him to a subject, and how watercolor helps him tell the stories of the landscapes he cherishes.

Kelly Kane: I know you dabbled in watercolors while at university, but can you talk about how you got started with them in earnest?

Tim Oliver: It was quite a while later, and I figured out pretty early on that I wasn’t smart enough to figure it out on my own. I ended up taking some lessons from another landscape architect and painter from Pasadena, California, named Richard Scott. He’s a very good watercolorist, and I would send him stuff and he would critique it for me.

Then things really turned a corner for me when I took a workshop with Iain Stewart in Alabama around 2010. I liked the way he handled the medium and decided that he was someone I should study with a bit.

Kane: Did lain introduce you to plein air painting? Or how did you first come to it?

Oliver: Actually, Richard Scott was holding a Sketching on Location workshop geared toward architects, landscape architects, and other design professionals. My lovely wife encouraged me to go and spend money that we didn’t have to attend – and thank goodness she did, because it ended up being a really transformational weekend for me.

In the mornings, we would work on concepts and techniques in the classroom, and in the afternoons, we would walk around Pasadena sketching with pen and ink mostly, and some watercolor. Richard was really involved with the Urban Sketchers movement that was beginning to take off at that time, and he encouraged us to see what other people were doing, as far as sketching, drawing, and plein air work goes. That was my first introduction to the concept that you could paint outdoors.

Fortuitously, when I got back to Lubbock, I visited one of my landscape clients, and a friend of hers, Barbara Rallo, was there talking about a new plein air event she was involved in starting in San Angelo called En Plein Air Texas. Barbara invited me to participate, but I didn’t feel I was near ready for that. Still, I did go down for their quick draw. I went a day early to scout out the location at Fort Concho, and found a spot off the beaten path with a little building in view. If the whole thing blew up in my face, I figured I could pack up and sneak out of town, and no one would ever even know I’d been there. In the end, I felt OK about the piece, so I entered it, and the awards judge, former PleinAir Magazine editor Stephen Doherty, said it was as good as some of the competition paintings, so he moved me into that category and gave me second place.

It was a pivotal moment, because I realized that maybe ifI work really hard at it, I may actually get to the level of those competition artists. I’m still in that mode today, trying to get better and better, so that maybe someday I can be.

Editor’s Note: Save years of struggle and frustration by discovering techniques revealed by some of the world’s top watercolor artists in just three days in the world’s largest online art training event January 26-28, 2023 with Beginner’s Day on January 25: WatercolorLive.com

Kane: How do you feel your day job in landscape architecture impacts your plein air work? What are the sensibilities that cross over?

Oliver: Being in a design profession, I’m accustomed to drawing and sketching, so I’ve always felt very comfortable communicating graphically with a pencil and paper. I think I was actually drawn to landscape architecture for the graphic component of the job; it certainly wasn’t the technical side – the math and all that.

I believe there’s a shared skill set in being able to see context in a place. In my landscape architecture, I’m trying to communicate the character of a place that I’m designing. With my watercolors, I’m interpreting an existing landscape in a fine art context. Both relate to conveying a sense of place.

Kane: Do you have favorite places to paint en plein air – spots that draw you back again and again?

Oliver: I tend to always be looking for the next thing, the next subject. On occasion, I have gone back to the same location multiple times. But when I’m done with a place, I tend to be done with it. I’m constantly on the prowl for something new; I want to move on and see what’s next.

Kane: What kinds of subjects most appeal to you?

Oliver: I was raised on a cotton farm, so the land is really important to me. Today I live in the high plains of West Texas, which is flat with no elevated landforms. It’s primarily an agricultural region. We’ve got 180 degrees of sky and flat horizons.

What always makes me want to pull over to the side of the road and paint is a landscape with a story – either a story that’s going on now or a story that happened in the past. I’m attracted to places where big skies and long horizons intersect with where man has been or is currently. It’s the abandoned farmhouse or grain elevator, or it’s the working grain elevator, with lots of activity around it. It’s not the majestic mountains, rivers, streams, and beaches that people love to paint. The subjects I’m attracted to are more mundane, maybe, but I’m drawn to those stories – real or imagined. I see an old farmhouse and I wonder, Who lived there? Were they happy? What tragedies did they live through in their lives?

Somebody once told me, “You know, you paint the things most of us would just drive right by.” I don’t know if he meant it as a compliment, but I took it as one.

Kane: How much of your work is currently done en plein air?

Oliver: My preference 100 percent of the time is to paint plein air. I love to set up outside and interpret a scene that I run across. The reality is that since I am still working full time and running a business, I don’t have that luxury, so I end up doing quite a bit of work in the studio.

I rely heavily on my sketchbook, which is always with me. I’ll make a lot of sketches when I’m out, and then turn those into paintings when I get time or when I get back to the studio.

Kane: When you do get to paint on site, do you typically like to finish the paintings completely, or do you bring them back to your studio for touch ups?

Oliver: I do both. Most of my plein air work is completed start to finish in the field. I may just do a little tweaking here or there after I’ve let the piece sit in my studio and looked at it for a day or two. Joseph Zbukvic calls it the French polish – fixing the little things you didn’t see when you were on location.

I’ve got seven plein air works in my studio right now that are about half done. I’ll either finish them in the studio, or I might take them back into the field and finish them there. But like I said, once I’ve painted something, I feel like I’ve explored it and I’m ready to move on to the next thing. I’m not a real patient painter, so I prefer to finish on site. That impatience probably explains why I like watercolors, which are so immediate. You get what you get and you go home.

Kane: What are the qualities of watercolor painting that you find particularly suit working outdoors?

Oliver: A lot of people would say watercolor isn’t the best medium for painting outdoors, and there are certainly some real challenges to it. I was painting in New Iberia, Louisiana, for the Shadows-on-the-Teche event in March, and it was kind of cool, cloudy, and windy. It was pretty wet most of the time, and I couldn’t get anything to dry. Here in West Texas, we have zero humidity 10 or 11 months out of the year, and the watercolors dry almost immediately, so I’m constantly misting the surface, trying to keep things active.

The challenge, however, is also what makes it is so exciting for me. Every day, I’m faced with something a little different. I have to be fast on my feet and adjust to what the climate and the medium are giving me. IfI try to control the watercolor too much, it can be really frustrating. I continue to work on giving up some control. I guess I’m like most painters – I’m either trying to loosen up, or if I’m too loose, trying to tighten back up.

Kane: You’ve talked about a few plein air invitationals you’ve participated in, but there aren’t always many watercolor artists represented in those events. Why do you think that is?

Oliver: I haven’t painted in a lot of events yet, because I just don’t have the time. But I’ve found that watercolorists who paint plein air, and I count myself among them, tend to be a bit evangelical about the medium; we see ourselves as missionaries of watercolor. We love the medium and we’re going to defend it to the end. People tease me, “So when you grow up, do you think you’ll be good enough to paint in oils?” as if watercolor was a starter medium. I say, “Well, maybe when I get watercolor painting figured out, I’ll think about another medium, but I’ve got at least 50 more years to go before I’ve got this one mastered.”

Connect with Tim Oliver: timoliverart.com

Save years of struggle and frustration by discovering techniques revealed by some of the world’s top watercolor artists in just three days in the world’s largest online art training event January 26-28, 2023 with Beginner’s Day on January 25: WatercolorLive.com

Visit EricRhoads.com to find out all the amazing opportunities for artists through Streamline Publishing, including:

– Online art conferences such as Plein Air Live

– New video workshops for artists

– Incredible art retreats

– Educational and fun art conventions, and much more.

> Subscribe to Plein Air Today, a free newsletter for artists

> Subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue