On Landscape Composition > Seasoned landscape painters know that rearranging the specifics of a location in nature is often a must in the creation of well-designed paintings, since natural settings are rarely arranged to conveniently fit the needs of a square or rectangular canvas. Because of this, artists often take a certain amount of liberties in the rearrangement of elements to suit their artistic aims.

This brings up the question of iconic locations that we painters have all come to love and dread at the same time! Their universally recognizable characteristics make any alterations next to impossible.

Take, for instance, the skyline of the Grand Tetons, not exactly a motif in which one can just eliminate a peak here, or randomly put one in over there, to augment the design of the canvas. Well, yes and no might be a better answer to that idea! Of course artists are free to do whatever they want; there really are no rules.

I remember seeing a reproduction of a painting of the Tetons when I was a teenager living in New York State. This canvas was painted by a very famous and accomplished artist, who did that very thing. It was a beautiful painting that just reeked of quality, yet the artist had put a peak in the scene, for artistic purposes, that is non-existent in real life. As a work of art, it didn’t matter at all, but there was this nagging problem of the actual setting, which locals and those familiar with the area would be sure to notice!

Related article > How to Paint Landscapes: Details vs. Design

The physical inconsistencies with the real location never occurred to me at the time. I had never been further west than New Jersey, so how would I know? Sometime later in life, when I was finally able to see the actual spot depicted in the painting, I just grinned and chalked it up to artistic license. To this day and after having painted in the Tetons for many years, I still think it’s a great painting. So the real question seems not to be one of dos and don’ts. Like it or not, it really comes down to a matter of consequences, which the artist is either willing or unwilling to live with. The one consequence that often dictates how artists paint, at least from the perspective of the galleries, is whether or not the painting will likely sell!

Now you might be saying, Who cares what the galleries think! One way or another, though, it is at least a consideration that each artist might want to take into account. How much are you willing to risk? The answers will vary here, according to the individual situations of different artists.

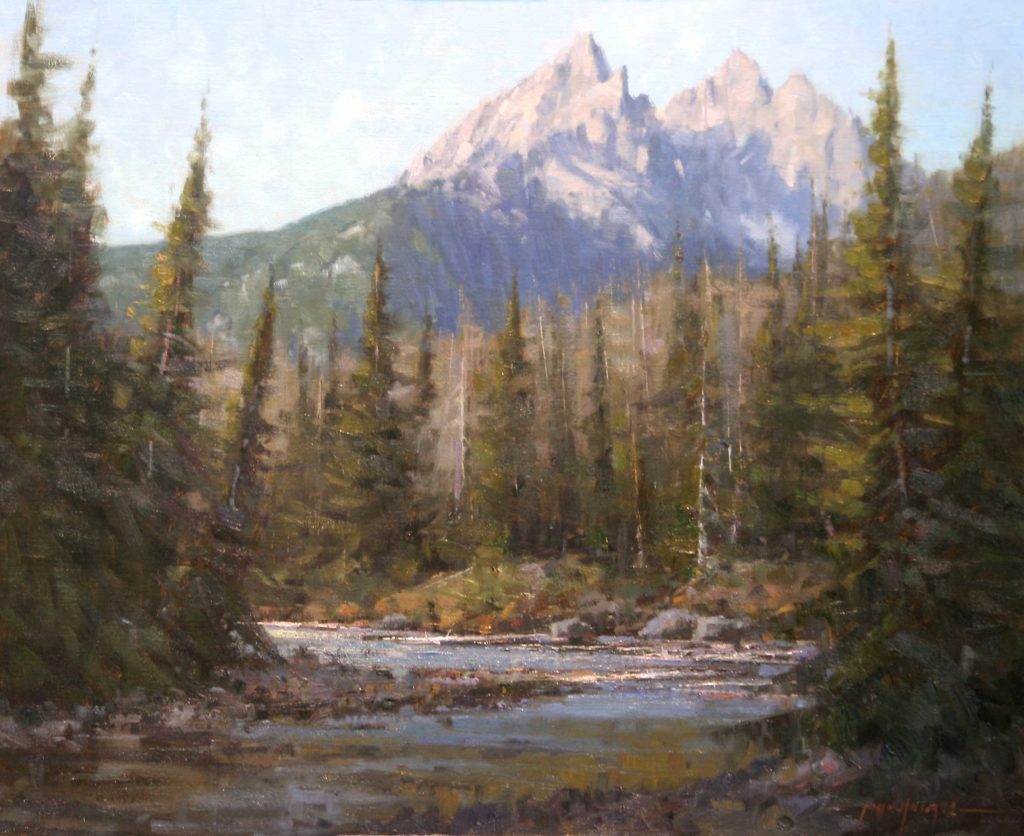

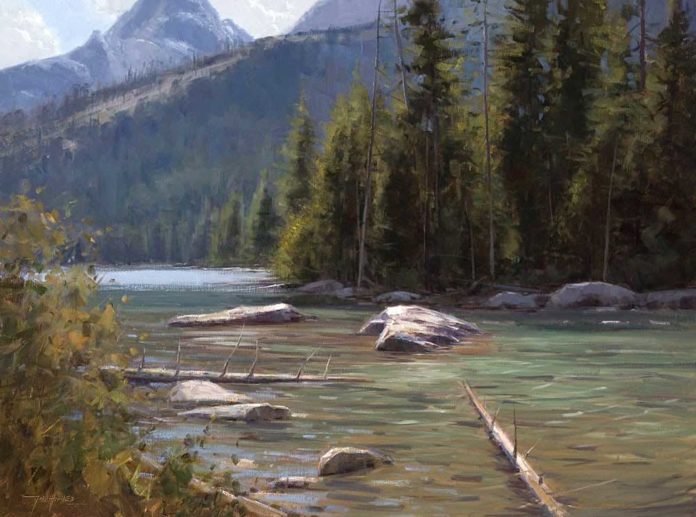

I remember a somewhat similar scenario that happened to me several years ago. I delivered a few paintings, including a 24 x 30 String Lake scene to a Jackson Hole gallery, which I was represented in at the time. There was a seeming problem with this one painting, and I was promptly told in no uncertain terms that it was a cardinal rule in that market, that one did not cut off the tops of the Tetons for any reason! Furthermore I was informed that artistic license didn’t apply when it came to those iconic mountains, and I was asked to take the painting with me when I left town that day!

I really saw the situation differently but was at a loss to explain why I thought he was wrong. The gallery owner simply didn’t appreciate my concept of a group of rocks and logs in the water that made for an interesting arrangement but cut off the tops of the Cathedral Group of peaks in the process. He actually said he liked the painting but wouldn’t be able to sell it. To my way of thinking, it was an artistic way of handling a familiar location in a somewhat fresh and different way. I felt that, in this instance, to include every detail and contour of those famous mountains would have unnecessarily competed for attention and robbed my focal point of the importance I felt it needed. A bit bewildered, I resigned myself to take the painting with me and try it out in a different market.

Interestingly, the painting was sitting on the floor of the gallery while I went to lunch with the owner, and afterward I picked it up, before heading back home to Salt Lake City. Several hours into the drive, just before Park City, Utah, where, incidentally, I was determined to take the painting to display in another gallery, I got a call from the Jackson Hole gallery owner, informing me that a collector had seen the painting sitting on the floor that morning and came back in the afternoon to purchase it! The gallery owner then asked if I would please ship it back as soon as possible! Gleefully I agreed. (By the way, for anyone who may be wondering if there is justice in the universe, there is!)

Having said that, I’m not opposed to that type of artistic license these days, but my general course of action is to take most of my artistic liberties with the non-iconic aspects of places like the Teton Range, just to avoid the hassle. If I do include a recognizable set of peaks, I will usually render the actual icon in a characteristic manner, staying faithful to their general form. This doesn’t preclude making artistic edits with the painting as a whole, though, because there are plenty of other ways to rearrange a scene of this type without endangering the spirit and character of the peaks. This can be done by using props such as rocks, streams, trees, and cloud formations to set up an arrangement that is artistically compelling while remaining true to the particulars of those recognizable icons. This gives the artist a whole range of options that makes room for personal representation without sacrificing the recognizable particulars of the location.

Like it or not, there are some subjects that will always present this dilemma to artists. Whether it be portraits, animals, ships with all their rigging, western subjects like horses and riders, or cityscapes, there will always be a certain expectation to get the details right. For instance, a moose painted with the wrong flavor of antlers in the wrong season, a ship’s rigging placed in the wrong position, or someone’s nose being too big in a portrait is sure to rouse the ire of some in your audience and draw sneers from others. Depending on your style of painting, these seeming errors might not even be a factor, but at least being aware of them might help you when planning your next composition of an iconic location or a recognizable motif.

***

To view John’s work and arrange for a workshop in your area, please visit johnhughesstudio.com.

Like this? Click here to subscribe to PleinAir Today,

from the publishers of PleinAir Magazine.

First and foremost an artist has the power to create. There’s an inherent freedom in painting that for example, a photographer doesn’t have access to without digital means.

No one can tell you who, what, or how to paint. If you’re not able to put your heart into a painting, I firmly believe that the quality of that painting and one’s love for art will suffer. This will be highly individual, but if that means replicating a scene in stunning detail, or taking artistic licence at every turn, do what feels right to you. Buyers will notice and appreciate the passion you put into that work and the ownership of the decisions that matter to you.

When taking artistic licence one way to push back is knowing how to market the piece. It’s not a painting of the ___ mountains, but a painting of a mountain, inspired by their beautiful landscape. There’s something powerful about calling it what it is, and complimenting local inspiration while doing so.

Thanks for your comment Zack!