Six seasoned pros share their knowledge on when a painting is finally finished.

Painting en plein air and working in the studio are practices that are sometimes pitted against each other, as though they were combatants in an arena where better and best duel it out. The truth is that the two go hand in hand in a sort of symbiotic relationship.

While plein air work may provide the initial spark, true values and colors, along with a rush of adrenaline, studio work has the advantage of time, for contemplative deliberation in the creation of an effective design.

Surely the two are not enemies, but part of a much bigger strategy, as they feed on each other in a way that advances the qualities of both. Working outdoors gives the spark of life to an otherwise lifeless studio rendition, which would wilt if it were not for the true understanding of light and luminous shadows, which can only be gained by artists who work outdoors.

When it comes to design though, the studio offers the luxury of time, which enables the artist to plan out movements, directions, connections, and placement of elements in a way that is not afforded the “shoot from the hip” approach that is so necessary on location. But what is learned in the studio is such a valuable asset to the quick-draw practitioners of the landscape craft; that the two approaches are truly beholding to each other.

Read on to find out some valuable lessons about finishing a studio painting, and treasure up the nuggets of wisdom that are also applicable to your next outdoor excursion to paint en plein air.

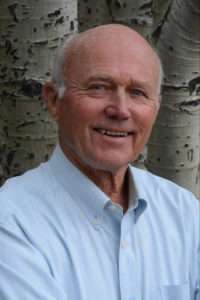

Jim Wilcox: Step Away and Get Another Opinion

Ideally, after I “finish” a painting, I’ll set it aside for a week or two and then look at it again to make sure “no one has sneaked in and ruined it” since I last saw it. Then I study it to make sure everything seems to be the right color and in the right place (with proper values, perspective, atmosphere, and design), then I’ll get out my mirror and check again.

If the painting has problems that I hadn’t noticed before, they are usually obvious when I reverse the image. Then I call my wife, Narda, into the studio to see if I missed anything.

She usually knows…I don’t know how anyone paints properly without a well-trained wife, husband, or honest friend with good taste and knowledge about art.

***

Peggy Immel: “Finishing a Painting: My Checklist”

Finishing a painting feels like the hardest and most time-consuming part of the whole painting process, even with a checklist that I dutifully follow.

After looking at the painting in a mirror, question number one is “Did I make my point?” I check the composition and eye flow. Is the center of interest, ahem, still the center of interest? Have I drawn everything accurately?

This is so important to check because one time I put three knuckles on a finger. I thought it looked a little weird.

I study the values, asking myself if I kept to my original value plan and whether any values jump out at me where they shouldn’t be jumping; things like a roof that is too light relative to what is around it, or a shadow area that has too much value variation.

How about the direction of the sun throughout the painting? Is it consistent and obvious?

Then I study the color. Is there any place that needs to be toned down? Anyplace that needs just a little more punch?

Once I’ve examined the painting, I make a correction list on a sticky note, put it on or near the painting and then get to work fixing all the stuff I have noted. At that point I go through the whole process again and again until I’m satisfied, or until the deadline for finishing the painting has arrived.

Frankly, it seems to me that no matter what, a little time away from a painting will always reveal just one more thing that needs to be fixed; like the time I walked into a group show that I was participating in, looked at my painting, and immediately had an almost irresistible urge to touch it up!

***

Steve Stauffer: “Are We There Yet?”

How many times have we heard this: “Are we there yet?” Or better yet, “Is it finished?”

As artists, each painting is like a journey. We might travel to a location and paint from life, or possibly take a field study or plein air painting back into studio as reference. Either way, we are on a journey that has been captured in fleeting light and expression.

From the beginning, each stroke is value, notes of color, light, and composition that will eventually lead us to a finished work. That being said, how do we know when it’s finished, and is a painting ever completely done?

I have come up with a term I like to use: “The Marinade Bucket.” I will turn a painting against the wall and not look or study it for a few days. Fresh eyes tend to locate problem areas of the supporting actors, which don’t allow our points of interest to shine the way they should.

I find myself so involved with certain aspects of the piece; I don’t really focus on the painting as a whole. I should take all the characters and players into consideration, no matter their importance to the piece and make sure they are all in harmony with each other and with what I am asking the piece to portray. Then and only then can I stand back and be satisfied that I’ve captured the essence of the journey with this painting.

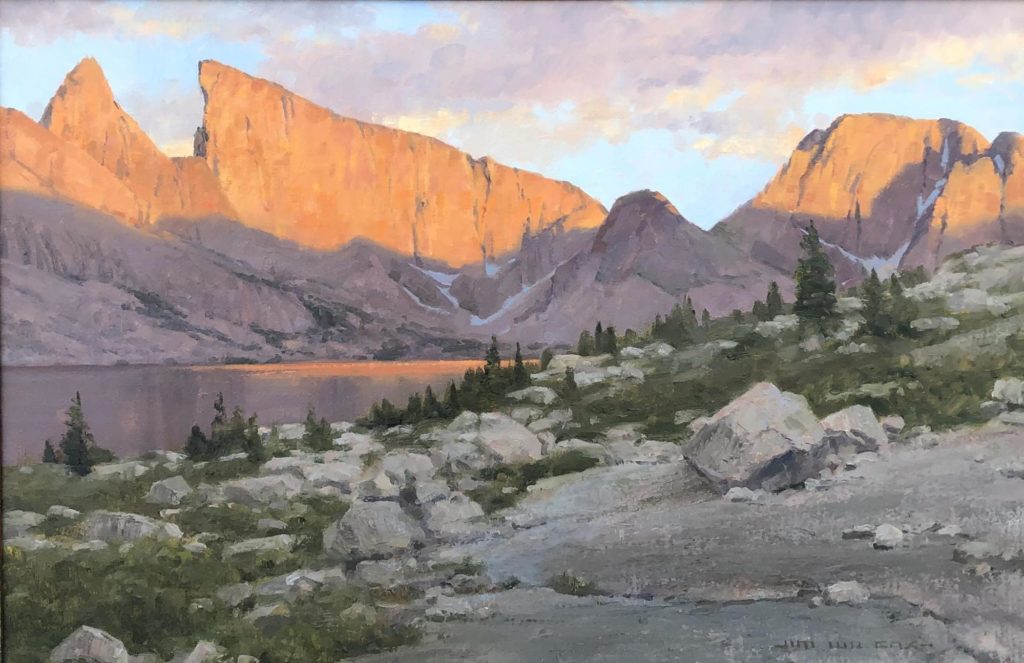

“Warming Rays” was one of those pieces that just didn’t come together easily. After being in “The Marinade Bucket,” I lighted the value of the hillside in the background and darkened the shadow on the road, allowing the light in this piece to shine. At that point I could say, “We are here, we’ve finished!”

***

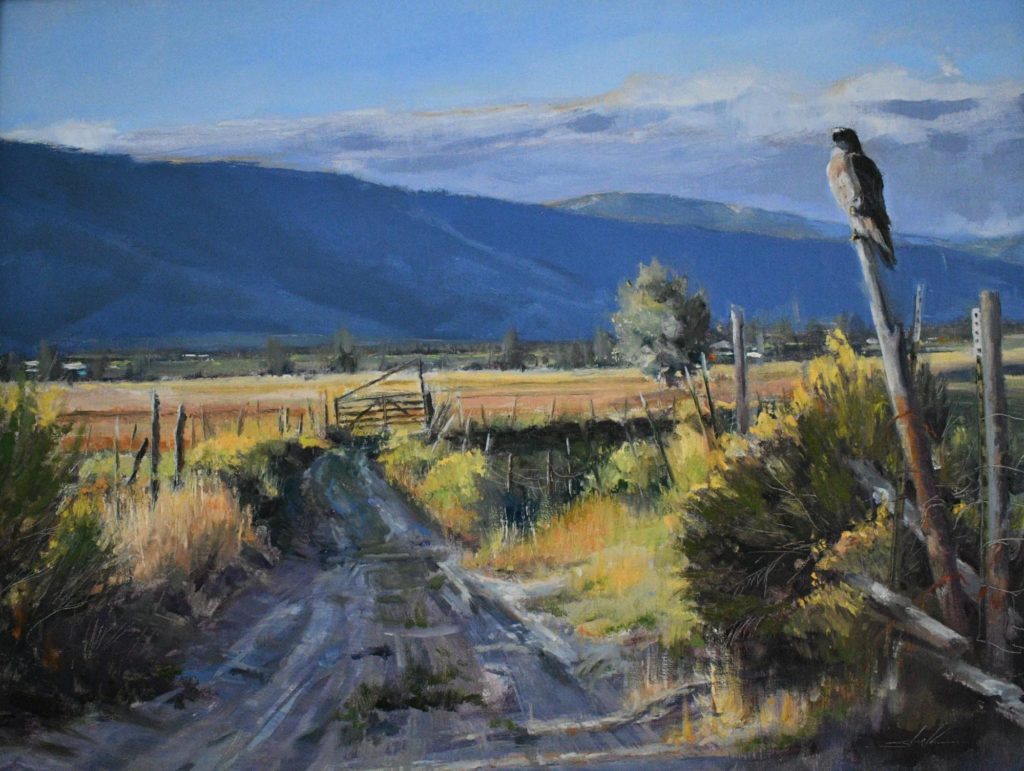

Wes Newton: “Painterly Distractions”

When I feel I have arrived at the last brushstroke I have gone through the process of looking for anything that sticks out that doesn’t help the painting, but distracts instead, therefore hurting the painting. That would include a color that sits alone that isn’t in harmony with the overall color scheme, one that’s too foreign.

Maybe a line or edge that’s too strong can become distraction to the viewer and detract from the work. An overly powerful value can also be out of place, drawing your eye where it’s not intended to go.

Is the painting balanced, so one side doesn’t feel like it’s going to cause the painting to tilt on the wall, figuratively, again being a distraction? So, distractions would be one of the most important aspects I look for at the end of a painting.

Oh yeah, don’t let your signature be a distraction either. Been there. Done that!

***

Allie Zeyer: “Looking for Subtle Nuances”

In the final stages of a painting I look for edges, shapes, values and transitions. I want to see a juxtaposition of soft and hard edges, which brings variety and interest to my work.

Subtle nuances and eye catching marks excite me as an artist, but they need to fit cohesively within large value shapes and planes. I look at my painting multiple times in a mirror just to double check my progress and see that everything is reading cohesively.

On occasion, I’ve even flipped my painting upside down to look at it from a new viewpoint. Undoubtedly, seeing the painting in this new “abstracted” manner I know exactly what needs improving; whether it’s an accent mark, a softer edge, or working a little more on my transitions.

At the end of the day it takes a lot of time, but the reward is great when you finally breathe a sigh of relief and call it done.

***

John Hughes: “Coming Back with a Fresh Eye”

Having worked on a studio painting over several sessions, it is often difficult to know when the painting is actually done, and it’s often very easy to overthink the matter. How does an artist know when the last brushstroke is actually the last one? What are some of the considerations that help in determining the answer to this vital question we all face at the conclusion of a major artistic creation?

First of all, I’m zeroing in on studio work in this article, due to different nuances in the answers that would be brought into play when working on location; but that’s a topic for another day, except to say that design challenges that are successfully overcome in the studio, will surely carry over into your location work as well, and make you a stronger painter outdoors.

When considering the question of studio finish, the first thing I do is to give myself some time away from the piece in order to come back to it with a fresh eye. This could be a few minutes, hours, or even days. Additionally, time spent observing the painting on the easel in a relaxed manner is also necessary to figuring out what the painting needs in the way of additions and subtractions before calling it done.

All too often our emotional involvement with a piece, especially one in which we have spent countless hours working on, can cloud our design sense when trying to make critical decisions about whether it’s finished; not to mention how successful our efforts are. When making these final decisions it’s important that an artist is well rested, coming back to the painting with a fresh eye.

I remember some years ago, working well into the late evenings on various large pieces in my studio, only to wind up destroying some of them that I thought were awful. This was usually done while viewing them from a fatigued state of mind and limited perspective as a result. The next morning I would usually regret my decisions after looking at the self- inflicted wounds on my studio floor. That all ended when my sweet wife, Teresa, made me promise that I would never destroy another painting at night, but wait for the morning to make better decisions. I have never regretted her council!

So then, the question of being done might involve several different points of consideration from design errors, over-modeled forms, confusing areas, and surface quality. I think the first thing I always ask myself is, “Have I said everything about the subject that I want to say?” After that I scan the image for design choices that don’t help the overall look of the painting, while keeping a sharp eye out for inconsistencies in such things as shadows or highlights.

Also, how much of anything is enough, and how much is too much? Are there any values that jump out at me and seem out of place?

Ultimately, after answering every question that I know to ask, I’ll leave it up on the easel as I leave the studio for the last time that day and make my final decision during those first few minutes of viewing it with fresh eyes the next morning. It’s that important first impression, as I re-enter the studio, that usually tells me everything I need to know.

Visit EricRhoads.com to find out all the amazing opportunities for artists through Streamline Publishing, including:

– Online art conferences such as Plein Air Live

– New video workshops for artists

– Incredible art retreats

– Educational and fun art conventions, and much more.

> Subscribe to Plein Air Today, a free newsletter for artists

> Subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue

Thank you for this article, as a newer painter information like this is really great.

A painting is finished when it says what you want it to say.

Love this article. Leaving the painting for a few hours, days, weeks, and coming back with a “fresh eye” to see what is missed will define if it’s finished. The paintings of the artists are just so beautiful and inspiring! Love the subtlety in most, and the colors and strokes are soft and nurturing.

Thank you for the advise. Just happen, I’m reworking paintings today, this has been very helpful.

I’ve discovered a strange shortcut to determine when I’m done. I take pictures during the development of the painting and when the photo looks worse than the painting does in person, I know I’m close to done. Obviously, this doesn’t nullify all the great ideas discussed above but just an observation.