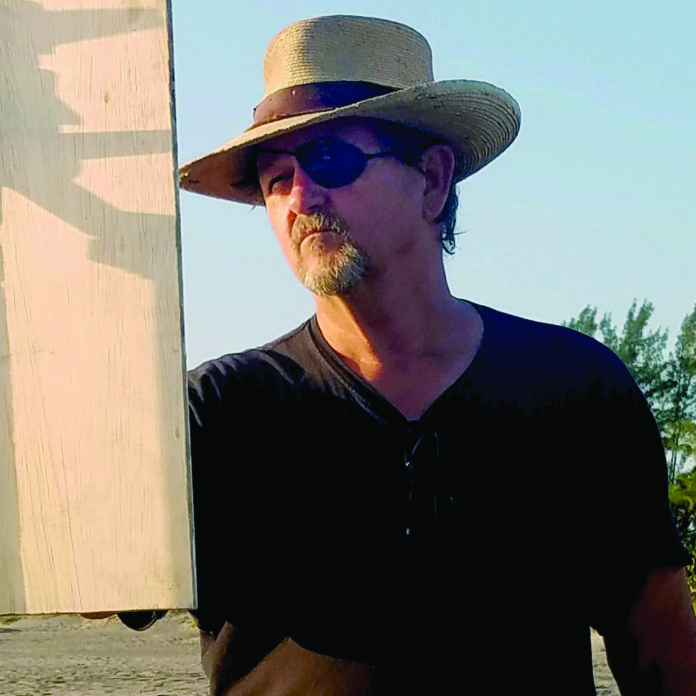

Loss of vision in one eye has taught this plein air painter that there’s more to perception than seeing.

Filling In the Gaps

by Lon Brauer

On a cold morning in late January 2015, I woke up with the vision compromised in my left eye. There was a split in the visual field from upper left to lower right. All above was fine; all below was dark. A trip to the eye doc confirmed it was a torn retina. All would be well, he said. “We fix these things all the time.”

In my case, it was not to be. I was that statistical 5 percent. There were surgeries and more surgeries — enough lasers to film a Star Wars sequel. Oil in, oil out. Water in, water out. In the end, they put the eye back together nice and tight, but I am stuck with a macular pucker that has effectively put that headlight out of action. Today, the vision in my left eye is like looking through a glass tumbler turned sideways … with ice. The right eye is fine, though, and I intend to keep it that way. I have to; it’s my painting eye. I now paint with one.

I share this story not to bemoan but rather to pass on some observations that might be of interest to other plein air painters. Painting is not just about pushing paint. The whys and wherefores are part of the journey. Understanding the mechanics of materials is the first part. Understanding the mechanics of how our brains make pictures is the rest.

They say the eye is a window to the soul. I wanted to explore that. Along the way, I got to thinking about a number of things related to painting and art-making in general. For example, how is it that we see, and how does that relate to what we perceive?

A number of years ago I taught a figure drawing class at one of the community colleges in St. Louis. I had students with some experience and some with none — all levels. My approach was very much about learning to look. Look at the model, measure, then draw. Simple, right? Well, it worked for me, and I thought it should work for everyone.

But drawing is more complex than that. Those of us who have been drawing since the day we picked up our first crayon rarely think of the mechanics. We just do it. Habits. I came to realize that the challenge for my students was not in the looking but rather in the perception and the interpretation. They would look all day long and then draw garbage.

Vision is not in the eye, but rather in the brain. The eye is a light receptor and an extension of the brain. It doesn’t really see, at least not in the way we generally think of sight. Light passes through a hole in the front, through a lens, and onto the retina. But that light has no practical meaning unless it is passed on to the brain for interpretation.

The eye is a tool. Patterns of light, value, and color go to the visual cortex in the back of the head as electrical impulses. There is no film plane or digital capture. No real image. It is all a construct — a memory. We perceive a thing, but there is no picture in there. We rely on patterns of light to interpret our surroundings in an appropriate way. And we do that through the use of memory and past experience. Everything that goes in is cataloged and stored for future use. And we all do it a bit differently.

A CASSEROLE OF IMAGES

Before I started painting seriously in 2010, I was a studio photographer. I had come out of school in the early ’80s as a figurative painter with uncertain prospects. By chance I picked up a part-time gig as a darkroom printer with a photo studio in St. Louis. It was in the heyday of advertising, and high-end photography services were in demand. I got sucked into this world in a big way, and it was art-related, so it felt good. I worked myself out of the darkroom in a short time, did photo assisting for a while, and then became a full-time shooter. I did it for 30 years, and I learned a lot along the way.

I worked every day with an 8 x 10-inch large-format camera — essentially a black box with a hole on one end, a pinhole camera. So, too, the eye is a camera. It is a device. Nothing more or less. A box, albeit ovoid, with a hole on the front end. Our eyeballs are set in our heads roughly 2 1/4 inches apart. Two cameras on one tripod. They work independently as well as in tandem, giving us two separate views of the same world. Our heads move from side to side to compound the information. All of these visuals go into our brains and get blended together. A casserole. We see an object from the left, from the right, and from the front — all at the same time. And with memory, we even have a sense of what is out of sight, what’s behind. Our brains fill the gap.

We perceive much more than we actually see. Our reference (our subject) for a painting is a moving target, not a still image like a photograph. We create variations on a theme in our heads, and then we add even more variables with the movement of time. The subject changes, and we make adjustments. What ends up on the canvas is never the same as the big party bouncing around between our ears.

MAKING ADJUSTMENTS

So what happens if one goes monocular? Are there significant differences? For me, there were some adjustments — mostly mechanical. I lost depth perception, of course. There’s more guesswork. Too often I have poured coffee on the counter, missing the cup. So I have found ways to get better info by touch. Grab the cup, then pour — that’s the secret. I have trouble hammering a nail; I bend a lot of them. Throw a baseball at me and I may catch it, or I may run away. It’s a bit scary.

I’m more cautious with my surroundings. I run into people on my left side because I really don’t know they are there. My right eye has to do all the work, and it gets tired. Floaters get in the way, so I swing my head to slosh them to one side. Strong light blows out the vision, and very low light is nearly useless.

As for painting, I think my work has actually improved — not because of the monocular vision, but in spite of it. My way has been to push the boundaries of shape and form, to establish a strong foundational drawing and then look for the vibrating edges. To this end, limited vision can actually be an asset. When I paint, I try to find the sweet spot of balanced light — not too bright and not too dark. Just as film has a limited exposure range, my eye can only play on a short field. Maybe it was always that way, even with two peepers, but I’m keenly aware of it now.

When you lose a tool, you learn that you need to adapt and find new ways to get the job done. Painting outside is difficult enough, but in certain lighting situations I really struggle. Shadows drop out or blend. Color choices become difficult. So what do I do about it? I spend more time thinking and conceptualizing on site to make things work. If I can’t actually see it, I draw from my experience to solve the problem. Am I making stuff up? Well, yes … and no. Maybe. But so what? My goal is to be true to the subject in front of me, but not married to it. I have found a freedom, by necessity, to explore and push the visual. After all, it’s about making a painting, not a photo representation.

Direct observation and memory are the two tools by which we make plein air paintings, and I would suggest that we rely on memory much more than we think. The more you know, the more you know. And the more you know, the more obvious are the gaps in your knowledge base. I find that there is always more to take in; it’s a constant learning experience.

I know what a tractor looks like and I could probably pull together a reasonable tractor painting, but I wouldn’t trust it. And if I don’t trust it, I wouldn’t expect the viewer to. We develop a symbol system for the objects we encounter. A gas station, a sewing machine, an airplane. We know these things when we see them. As artists we task ourselves with understanding all this stuff in terms of shape, form, and space. Basic survival requires that we recognize the difference between a rabbit and a tiger immediately, so we can react. But to draw those creatures as objects in space takes a lot more exploration.

MAKING MEMORIES

Plein air painting is lauded because it requires direct observation. And so it does. We pack our gear, throw it in the car, go to a location, set it all up, and then paint what is in front of us. We see it and translate it to the painting surface. If it’s there, we put it in. If it’s not, maybe we don’t. We know what we’re looking at, but the complexity is beyond our experience. We are there to get new information — to fill in the gaps. We look at the barn, and then we mark the canvas, then back to the barn, and back to the canvas, over and over again until we’re done.

Each time we turn to the canvas, we are using short-term (eidetic) memory. We have a memory image that we try to retain long enough to get it down on paper. When it fades, we look again. We gather visual information for our brains to interpret. We then translate with paint what we see in our mind’s eye. The specifics of this memory will be lost in a short time.

It’s fleeting and at best will become a mental generalization. In our daily lives, that’s just fine. When we see another barn, we will know that it is indeed a barn and not a frog. But for the artist, it is valuable to try to retain as much of this memory as possible for the future of the pursuit. We must build our memories; they make up the visual ingredients we cram into our brains.

We all want to make a painting. That’s the goal. That’s why we keep going out. There isn’t anything else. To do this, we need to find a balance between what we know and what we see. What we know is our history — our visual history. We draw from what we have seen before and what we have experienced. That history drives our choices and our aesthetics as we try to make a picture. What we don’t know is new and unfamiliar, and that is where direct observation — concentrated looking — comes into play. We see it, incorporate it, and interpret it. And ultimately build on memory.

Are two eyes better than one? Of course. But maybe, just maybe, that makes it all too easy. Can one eye do it alone? You bet. And, hey, I get to wear an eye patch. Who doesn’t want to play the pirate?

Coming of age in the early ’70s, Lon Brauer has roots in the abstract expressionist movement. Influences of Jasper Johns, Willem de Kooning, Cy Twombly, and Anselm Kiefer still play through his work. lonbrauer.com

Visit EricRhoads.com to find out all the amazing opportunities for artists through Streamline Publishing, including:

– Online art conferences such as Plein Air Live

– New video workshops for artists

– Incredible art retreats

– Educational and fun art conventions, and much more.

> Subscribe to Plein Air Today, a free newsletter for artists

> Subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue