“The working process is intense and concentrated . . . and it IS work.” Plein air painter Harry Stooshinoff shares his inspiration for continuously painting the landscape.

Painting the Landscape: “On Lost Dog Hill”

BY HARRY STOOSHINOFF

DeKooning spoke of being a “slipping glimpser” . . . the way you have this little sense that you might be getting close to something that is desirable, that you want, that enchants you . . . and then it’s gone . . . It’s elusive. You try to reveal something, but you don’t have a very clear idea of what that thing is, or exactly how to get at it . . . so you feel your way, over and over . . . Sometimes you’re closer, and sometimes farther away . . . a slipping glimpser . . . like a memory fragment from childhood that’s almost completely gone . . . just a hint remaining.

You go on . . .

If you go for an hour walk in the country and look around you will see hundreds of things of note—so many that it doesn’t even seem possible to comment on them all or reference them in paintings. You look at something, and the image combines with another thought or sentiment running through your head, and the whole mood and meaning of what you are seeing changes.

You look at the sky and note a motif . . . walk ten paces forward, look again in a slightly different direction and something equally interesting presents itself. And so it seems that very few things are actually noticed, and very few things are actually painted. There are a million more things that might be done with the landscape in paint.

The problem is always the same: how to take sensations, impressions, visual or otherwise from the world, and use them to impart some quality of life in the making of a picture. Over time you develop all sorts of tools to help you do this . . . colour mixing knowledge and colour theory, observational drawing ability, design sensibility, understanding how creative flow works . . . but the process is mysterious and there are no clear guarantees.

Always the guiding question remains, “Does the painting seem to have an independent and palpable life?” You stop the painting at or near that point, when you’re in the vicinity . . .

I live in the rolling countryside of the Oak Ridges Moraine, an ancient landform located just north of Lake Ontario, and am inspired by what I see every day. I roam this unique place in all seasons, and document my impressions. At first view, rural environments may seem natural, but they have been continually altered and reshaped by man.

The landscape will be very different tomorrow; it seems almost negligent not to record how it looked and felt today. It’s a big NOISY world, so I make small, quiet paintings. There is a desire to leave something thoughtful behind . . . to say in some manner, this place was essential . . . we were together for a long time, and it touched me in this certain way.

Each picture is in some way a continuation of the piece that came before . . . forming a long line of influence. My mood very much influences each piece. My interior life is a constant filter through which all responses to the landscape are channeled. So there is no “pure” landscape . . . it is “my” landscape. But the location also seems to have its own force that called it to my attention in the first place. This quality of place remains strong through the painting . . . the subject is like another strong personality always in the room.

The painting process also calls for an unknown and as yet undefined beautiful balance. You need some of this and some of that. You make things up as you go along, and you stop at some point when the picture seems to have independent breath. All sorts of subtle forces need to be balanced into a beautiful unity. All these necessities mix together in some strange flux . . . so nothing is ever permanently stable. And the only solution to the instability is to make something else.

I always start and finish a work in one sitting, and have for many years. The working process is intense and concentrated . . . and it IS work. There is constant movement, continuous decision-making, fierce attention to every mark and “touch” made, no letup at all for a period of about two hours. Every line serves a purpose in the balance. There can be no extras.

The aim is always to let the work somehow suggest the quality of breathing, and the constant courting of surprise. If some passage looks overly deliberated, studious or conscientious, the sense of surprise is diminished; any changes made must be significant and not mere embellishment.

Working on an intimate scale encourages a greater willingness to take creative risks necessary to achieve this sense of surprise. This repertoire of techniques and methods may or may not guide me the entire way. The enterprise must be open to continual reinvention, always seeking if the process answers the question: “Is this work more real and alive now?”

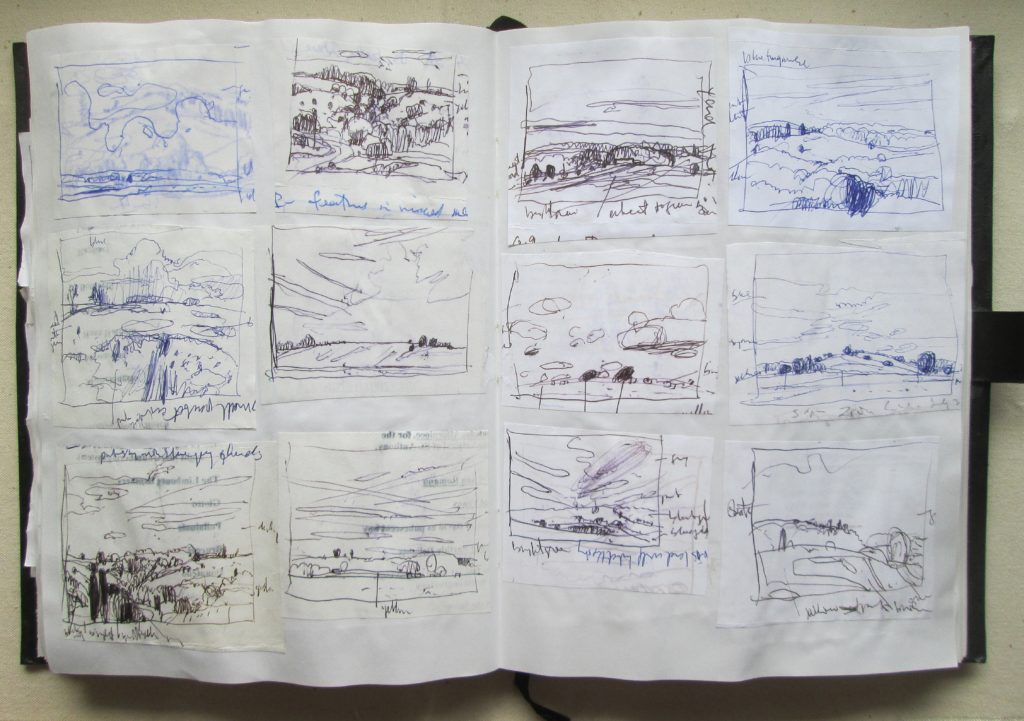

To make the process continuously new I alternate my methods. I often use small one-minute diagrams made in ballpoint pen on folded-up typing paper kept in my breast pocket. I quickly jot down the three or four elements in relation to each other that make up a visual motif in the landscape. These little drawings serve as reference for the paintings made in studio.

If this process becomes too automatic, the next few pictures might be made from memory, to again allow new elements to enter the process. Or I will start the work with collage—three to four essential colours in relation to each other can form the basis for the whole work. This collage starting point might then be brushed over with acrylic.

At times the attempt is made to see how simple a work can become to match an effect noted on-site in the landscape. Working on a small scale allows me to easily follow hunches that might result in oddness or awkwardness in the piece; oddness can be indulged . . . what’s the harm? I resolve the work in one sitting and let it exist.

Learn more about Harry at: harrystooshinoff.com

View and purchase Harry’s work at: paintbox.etsy.com

Visit EricRhoads.com to find out all the amazing opportunities for artists through Streamline Publishing, including:

– Online art conferences such as Plein Air Live

– New video workshops for artists

– Incredible art retreats

– Educational and fun art conventions, and much more.

> Subscribe to Plein Air Today, a free newsletter for artists

> Subscribe to PleinAir Magazine so you never miss an issue