In this series of articles, Utah artist J. Brad Holt talks about what artists are seeing as they look at the landscape. Holt studied geology in college and is attentive to what the rocks suggest in the scenes he paints.

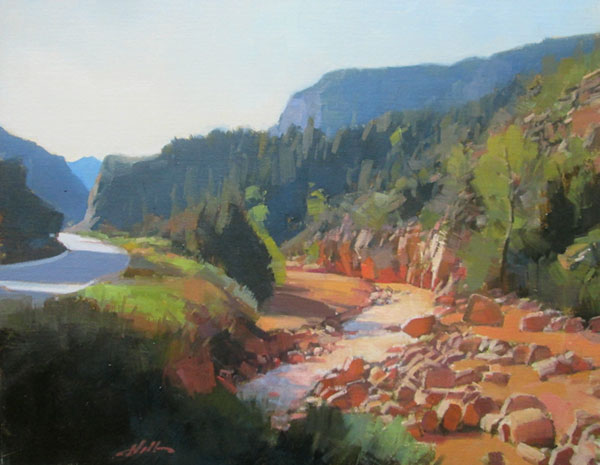

Lead Image: “Cedar Canyon—August,” by J. Brad Holt, 2015, oil, 14 x 18 in. Studio painting

The earth of 500 million years ago was very different in appearance from what we see today. The disposition of landmasses and oceans was vastly different, and the life forms that inhabited the planet were all beneath the waves. In the equatorial latitudes of the Western hemisphere, the future North America was a continent called Laurentia, comprising Greenland and Northeast Canada. East of this was the proto-Atlantic, or Iapetus Ocean. Continuing east, we pass a small mountainous continent that will one day be Siberia. East of this is the Tornquist Sea, in which sit Baltica and Avalonia, which will become Europe and Newfoundland/Nova Scotia. East of this is the vast bulk of the supercontinent of Gondwanaland, comprising Africa, South America, Antarctica, India, and Australia. This land mass extends south into the polar regions. The actual South Pole was in the north central part of Africa. Evidence of ancient glaciation can be found today in Ordovician sandstones in the Saharan desert.

Shallow seas off the west coast of Laurentia and the north coasts of Gondwanaland were conducive to the formation of marine limestones that today form the bulk of early Paleozoic strata in North America and Asia. Fossil evidence shows the widespread development and distribution of marine algae colonies, shelled invertebrates such as brachiopods, and chitinous scavengers such as trilobites. Gastropods, mollusks, and crinoids developed and thrived through the Ordovician Period, and by the beginning of the Silurian, the first primitive land plants began to establish themselves.

In the Silurian Period, the Iapetus Ocean closed. Siberia drifted north, and Baltica and Avalonia drifted west to crash into Laurentia. This was the beginning of the Caledonian Orogeny, a complex series of mountain-building events that would eventually result in the formation of the Appalachian/Caledonian chain. Gondwanaland drifted south and west so that the bulk of it was situated south and east of Laurentia/Baltica/Avalonia. The east-west trending sea between them was called the Tethys Sea.

The Tethys Sea persisted long in the history of the world. The last vestiges of it today are seen in the Mediterranean, Black, Caspian, and Aral seas. Great shallow tidal basins occupied the western parts of Laurentia, which by this time was entirely south of the equator. These basins dried out from time to time, creating widespread evaporite deposits.

The Devonian Period saw the appearance of spiders and insects, and the development of armored, jawless, and bony fish groups. Coral reefs, which began in the Silurian, became widespread in shallow tropical seas. In Laurentia and Europe, great quantities of alluvium eroded from the Caledonian Mountains to form thick deposits of mudstones, shales, and sandstones, which are the hallmark of Devonian strata in the Northern Hemisphere. The first vascular plants appeared on land at the end of the Silurian. By the end of the Devonian, forests had begun to spring up. Devonian lungfish fossils from dozens of sites in North America and Europe indicate that amphibians were about to take over.

In the Carboniferous Period, there were three continents. Laurentia, containing the future North America and Europe, straddled the equator. To the northeast was a continental mass called Angaraland, containing Siberia and parts of Asia. The Southern Hemisphere contained all of the rest of the future continents together in the vast bulk of Gondwanaland. Land plants proliferated and developed into great swamps. Amphibians became widespread. Spiders and insects diversified. The first true reptiles appeared. Late in the Carboniferous, the Tethys Sea closed between the north coast of Gondwanaland and the southeast coast of Laurentia, bringing in the final phase of the Appalachian Orogeny.

A vast range of mountains now stretched from the future area of Texas northeast to Newfoundland, through England, Scotland, Norway, and Spitzbergen. This vast continent, now known as Pangaea, contained all of the continents except Angaraland, which was drifting southwest. By the end of the Permian period, it would crash into Laurentia, creating the Ural Mountains. This marked the end of the Paleozoic Era. All the continents were joined in a true Pangaea. It also marked a significant event known as the Permian Extinction. More than three quarters of all the plant and animal life on the planet died out at this time.